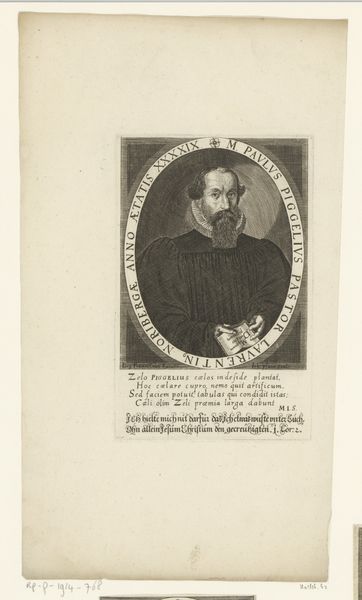

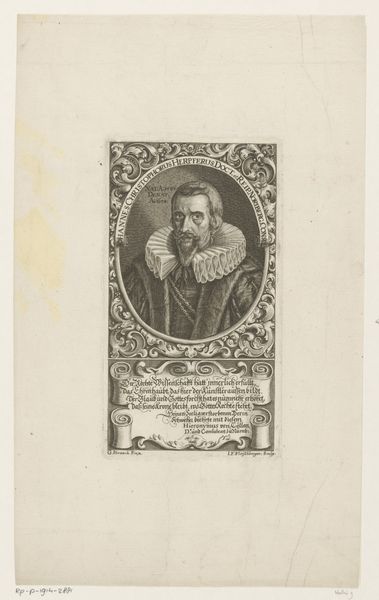

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

old engraving style

#

mannerism

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 139 mm, width 103 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

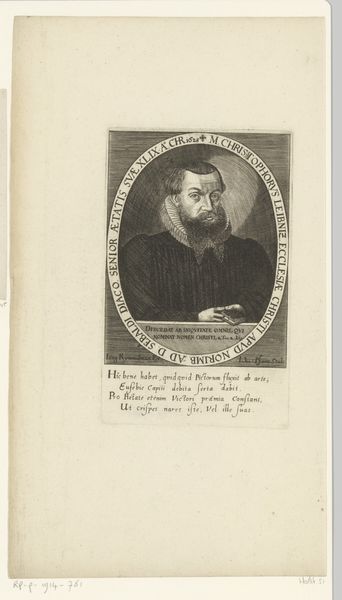

Curator: I’m struck by the precision of line in this portrait. The figure seems carved out of the very page. Editor: Indeed. We are looking at a print, an engraving entitled "Portret van Chilian Vogler," made in 1596 by Jakob Lederlein. Consider the layers of labor here, from Lederlein, the engraver, to the sitter Vogler and finally the press that must have replicated the portrait multiple times over. It’s a complex web of making and distribution. Curator: It’s fascinating how these early prints served almost as a form of accessible, reproducible fame. Vogler, we read in the inscription, was a doctor, a professor, and a counselor to the Dukes of Württemberg. So the image served to promote this elite status in some fashion? Editor: Absolutely, it reinforces social hierarchies by immortalizing a figure of authority and distributing it through an emerging visual culture. Notice, too, the framing cherubs. Are these mere decorations, or do they speak to Vogler’s role as both intellectual and spiritual advisor? Curator: The cherubs, to me, speak more to the style than the specific message. Mannerism was a widespread style that shaped not just art but also cultural expression, courtly gestures, fashion and all other areas of human life. Editor: Good point. Yet this distribution must also have impacted how notions of power were visualized and consumed across social strata. Imagine owning a small print like this, bringing into your home an effigy of those in power, even if as a way to remind yourself of the prevailing order of things. Curator: It's not a photograph though. What do we know of Vogler's actual likeness? The engraving would not capture the exact likeness. There may be changes to it, and the prints are sold, traded. The point becomes the art in and of itself, the visual experience rather than the precise person. Editor: A visual experience tied to socio-political status. Whether a perfectly true depiction or not, this print still provided access to the face and reputation of a figure of authority, contributing to the construction and reinforcement of his image within the broader society. Curator: It highlights the transformation that takes place in art when the creative act involves a production of replicas. The art becomes a concept. Editor: Ultimately, it is an intriguing reminder of how power, portraiture, and print culture were deeply intertwined in the late 16th century. Curator: Precisely, the making of the piece emphasizes how we consume its legacy today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.