drawing, paper, fresco, ink

#

drawing

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

paper

#

fresco

#

21_yuan-dynasty-1271-1368

#

ink

#

china

#

line

#

calligraphy

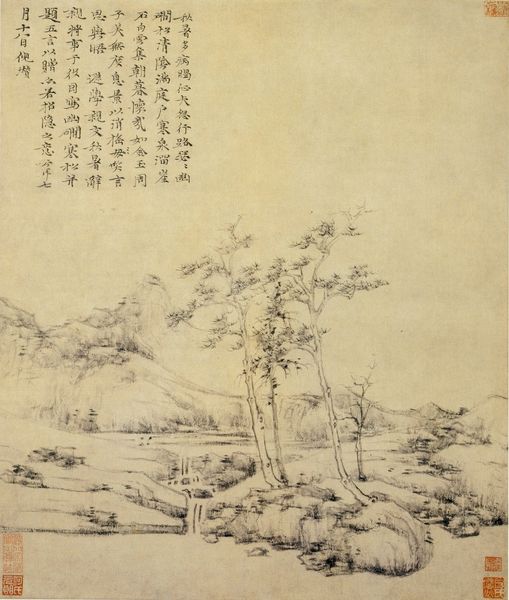

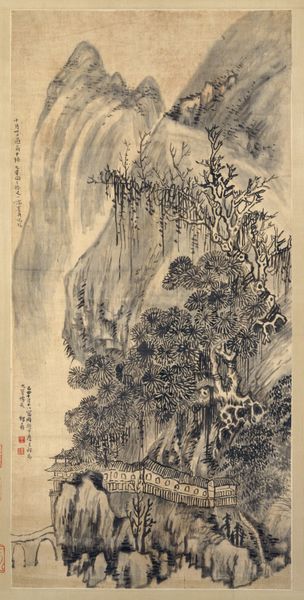

Dimensions: Image: 38 5/8 × 27 1/8 in. (98.1 × 68.9 cm) Overall with mounting: 8 ft. 10 7/8 in. × 35 7/8 in. (271.5 × 91.1 cm) Overall with knobs: 8 ft. 10 7/8 in. × 40 in. (271.5 × 101.6 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Welcome. We're standing before "Enjoying the Wilderness in an Autumn Grove" by Ni Zan, a work created in 1339, during the Yuan Dynasty. It resides here at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: It’s quiet, contemplative. I’m immediately drawn to the almost monochromatic palette—various grays, ink washes on what looks to be aged paper. The texture is incredibly important here. Curator: Absolutely. Observe the use of line – crisp, defined, and almost architectonic in its representation of form. The bare trees, the precisely rendered rocks. It is classical form expressed using simple means. Consider too, the calligraphy at the upper right. Editor: Yes, but even those “simple means” speak volumes about craft, time and labor, I wonder how long it took Ni Zan to achieve that effect? Also the context, though— the political instability of the late Yuan Dynasty certainly shapes Ni Zan's desire for retreat. Wilderness wasn't just a pretty picture; it was refuge. What do we know about the pigments and the specific techniques used to layer the ink, creating depth? Curator: We understand that the paper support informs the technique – controlling the ink bleed. In that sense, the artist uses formal methods to express an attitude of reclusion. Observe the placement of the pavilion; almost hidden amidst the rocks. This formal device draws the eye to its relative smallness, suggesting the unimportance of habitation in such a setting. The poem, itself, discusses just this detachment. Editor: But it wasn’t only the paper that controlled the bleed, but Ni Zan himself, controlling every variable of ink, tool, and hand to master form through control. Thinking about this now makes me ask myself where the pigment was sourced and processed, even distributed during a time of significant social disruption. That interplay of individual artistry and collective conditions interests me. Curator: Well, through our formal lens, we interpret Ni Zan’s starkness, this simplification of form, to embody the Daoist principle of wu-wei, or non-action. Editor: Perhaps we see these bare forms in front of us very differently indeed, and for both of us to linger within the world of artistic practice feels more enlightening than ever. Curator: Yes, indeed. This rigorous formal design echoes even louder than before.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.