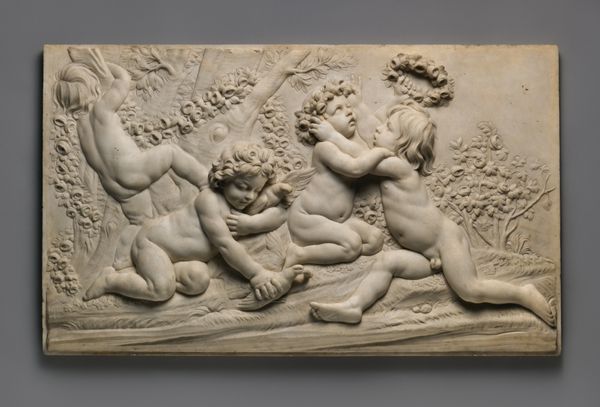

carving, sculpture

#

carving

#

allegory

#

baroque

#

sculpture

#

figuration

#

female-nude

#

cupid

#

sculpture

#

carved

#

decorative-art

#

nude

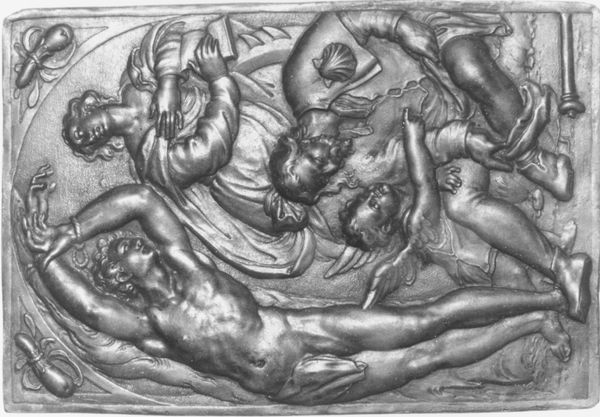

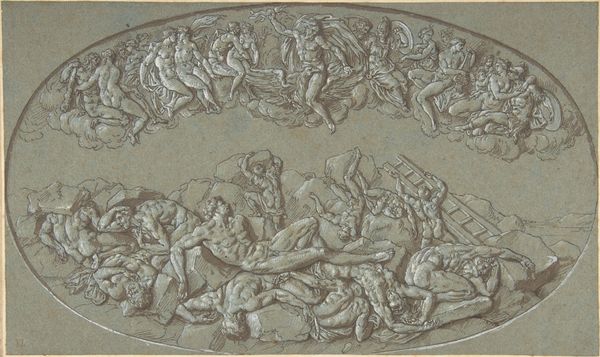

Dimensions: Overall: 4 9/16 × 7 1/16 in. (11.6 × 18 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Immediately, what strikes me is the dynamism! It's such a frenetic scene, the figures seem to leap off the panel. Editor: Indeed! What we're looking at is a Baroque carving from sometime between 1715 and 1735 entitled "Apollo and Daphne," housed here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It's the work of Andrea Brustolon. The story is right there in the title. Apollo, the god of music and light, is in hot pursuit of Daphne, a nymph dedicated to the goddess Diana. She flees, praying for salvation, and just as Apollo reaches her, she transforms into a laurel tree. Curator: And it's all rendered in such detail! I am drawn to the figures' emotionality, with Cupid, who instigated the chase, hanging above. The musculature of Apollo contrasts so intensely with Daphne's supplication as she sprouts into a laurel. Editor: Brustolon really captured that metamorphic moment! Think of it: a powerful god’s desire denied, countered by a woman’s agency, finding freedom through radical transformation, albeit one imposed by other patriarchal forces. How do we reconcile the violence of Apollo's desire with Daphne's forced transformation into an object? The relief underscores the societal objectification and silencing of women. Curator: The scene reflects a struggle over bodily autonomy. While it illustrates the narrative of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the choice of carving such a dynamic scene reveals something of the political landscape in which this work of art was crafted and would circulate. What did such dramatic tales say about power relations? What role might powerful collectors have played in perpetuating this type of imagery? Editor: I think the prevalence of these mythological narratives during the Baroque period really cemented a social structure in which such acts are not only seen as powerful but are presented as a normal function of power, the "order" of things, thus naturalizing gendered violence. Curator: Looking closer, I admire Brustolon's carving skill in wood—notice the rich surface. From a curatorial perspective, it represents an interesting example of the circulation and collecting of mythological scenes during the late Baroque, telling us something about the role of art in representing authority and shaping cultural mores. Editor: It invites us to confront not just the artistry of the piece, but the insidious normalizations it might perpetuate and reflect upon our own contemporary narratives surrounding gender, power, and consent. We must consider these layers to fully comprehend its power.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.