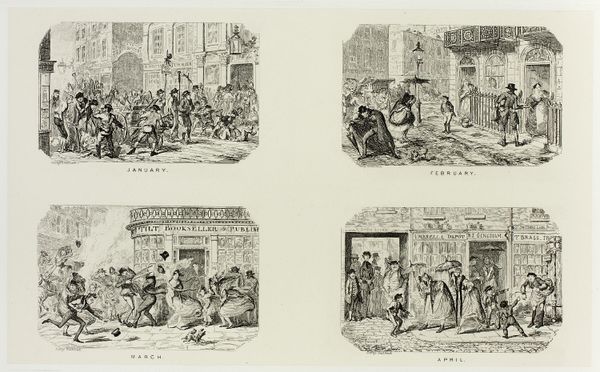

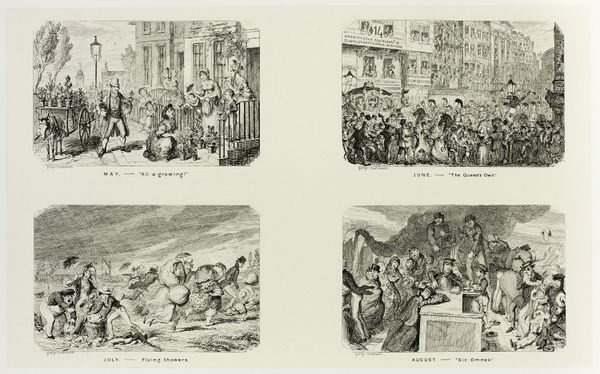

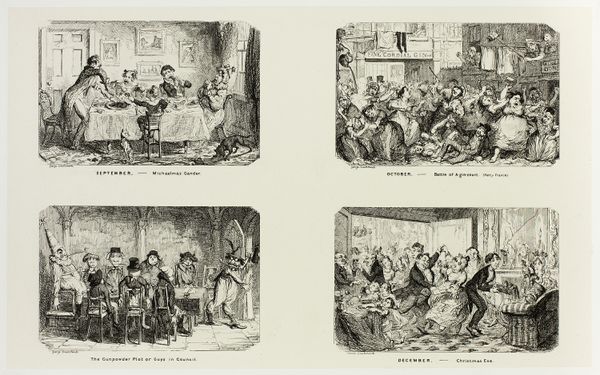

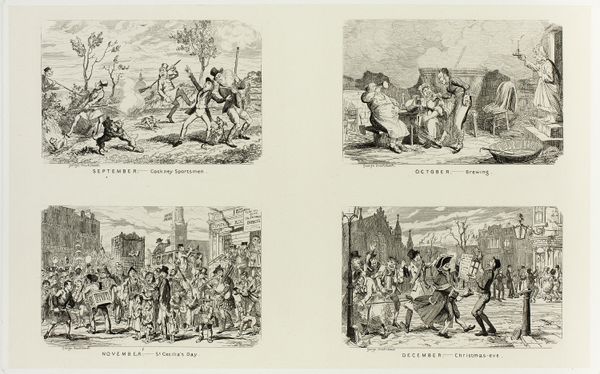

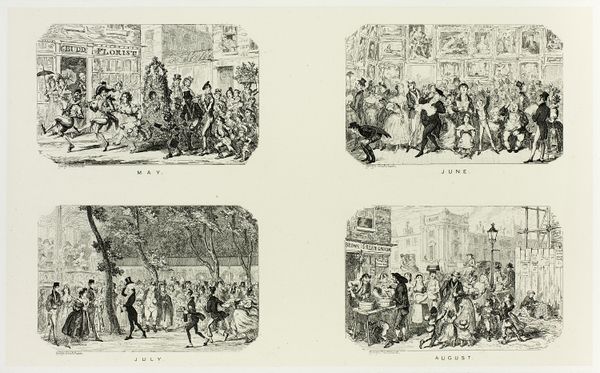

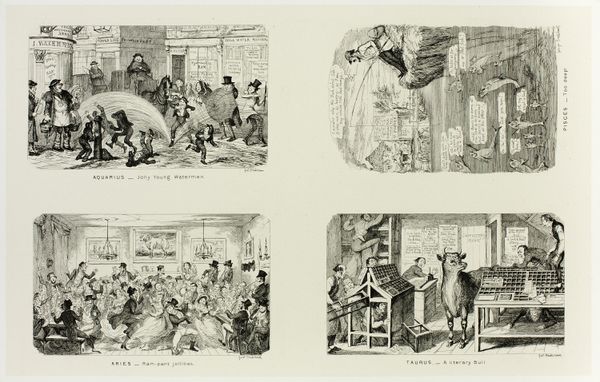

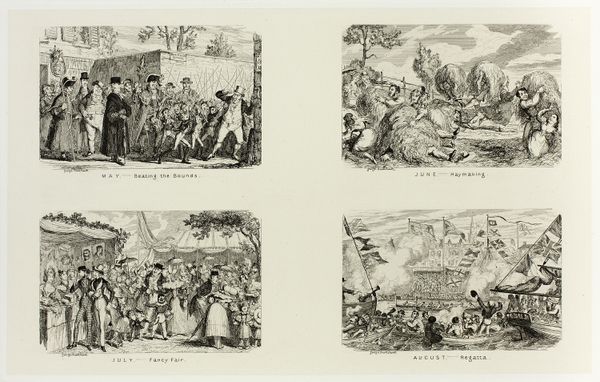

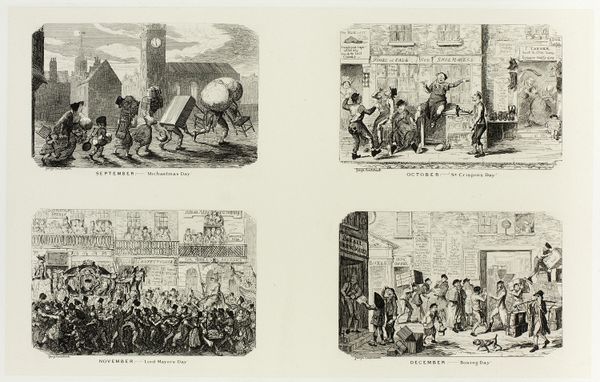

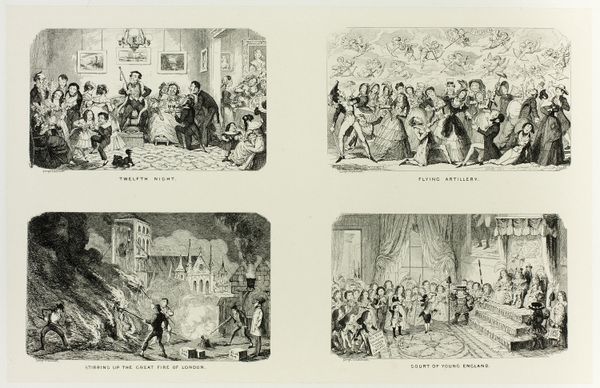

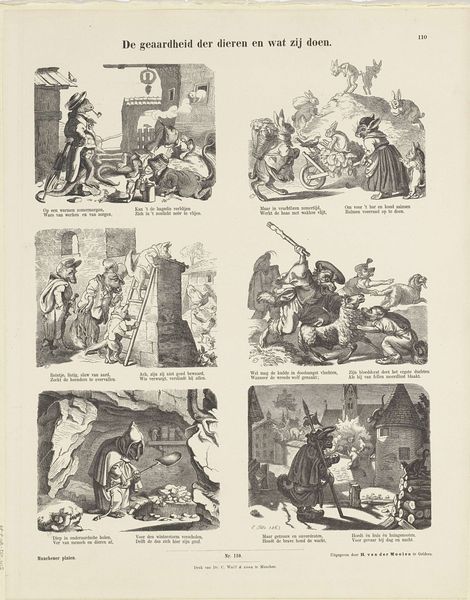

January – Last Year's Bills from George Cruikshank's Steel Etchings to The Comic Almanacks: 1835-1853 (top left) c. 1837 - 1880

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, etching, paper

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

paper

Dimensions: 207 × 333 mm (primary support); 342 × 507 mm (secondary support)

Copyright: Public Domain

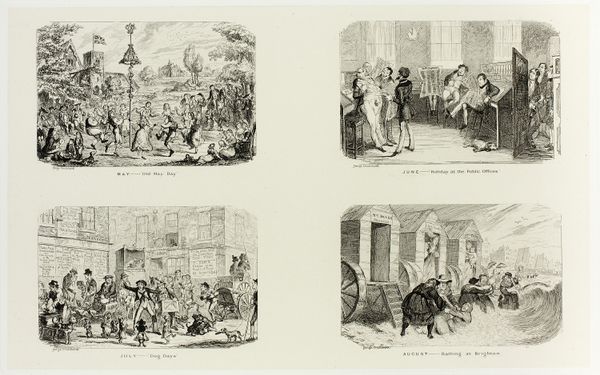

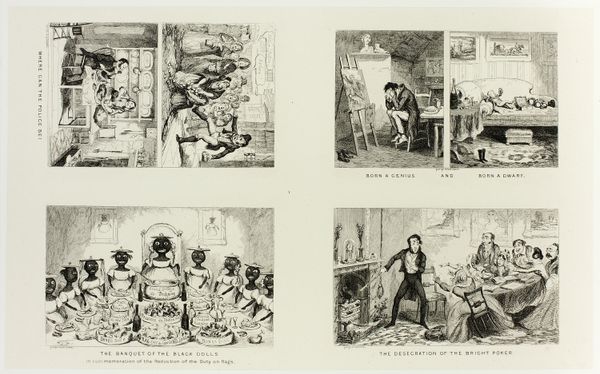

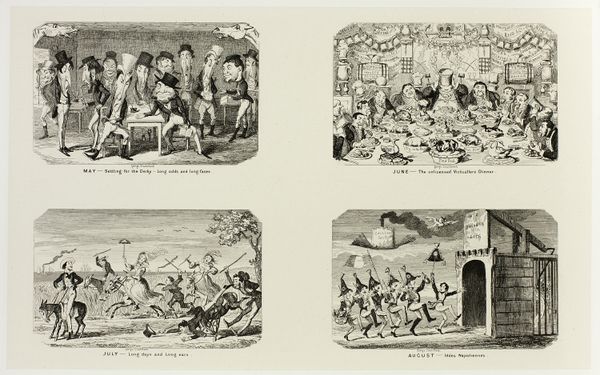

Curator: Let's look at George Cruikshank's print, "January – Last Year's Bills" taken from his Steel Etchings to The Comic Almanacks, created sometime between 1837 and 1880. The piece is a stark etching on paper, currently residing here at the Art Institute of Chicago. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: Chaos! Pure visual chaos. The composition is crammed with figures and details, making it initially overwhelming, but it hints at deeper societal narratives. Curator: Indeed. This image speaks volumes about the socio-economic realities of Victorian England. "January – Last Year's Bills," at first glance, might just seem like a comedic depiction of domestic disarray. But let's break down some of its symbolic weight. Note the figure of "Father Time" ushering in the New Year, whilst burdened by a towering stack of overdue bills, looming over a family attempting to find warmth by a hearth. Editor: The fire becomes symbolic not only of warmth but also perhaps refuge. I see the clustering of figures and sense a desperate yearning for comfort and security in the face of economic precarity. Bills as symbols – aren't they heavy with their implications for status and worth? And "Father Time," isn’t that also a commentary on the never-ending cycle of debt and responsibility? Curator: Precisely. The artist uses powerful cultural imagery here to underscore issues around debt. Notice the smaller, more personal items being overtaken by those 'spirits of debt'. It highlights the pervasive anxiety caused by financial instability. Moreover, consider how Cruikshank uses satire, and exaggeration to critique these social systems that create inequality. Editor: It is amazing how potent the symbolic language here is. Each figure has symbolic significance, all rendered with painstaking precision. I notice particularly the way light is used to both reveal and conceal, suggesting the opaque nature of power, and, in this instance, systems of economic oppression, even within domestic spaces. The detail in the ghosts of bills themselves almost renders them characters in this drama. Curator: Absolutely. The brilliance of Cruikshank lies in his ability to pack so much cultural commentary and symbolism within seemingly simple scenes. Editor: I agree. It reveals that a seemingly straightforward scene of January and old bills holds much broader lessons for modern society about the relentless burden of time and bills! Curator: And a valuable insight into how visual shorthand carries such potency throughout generations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.