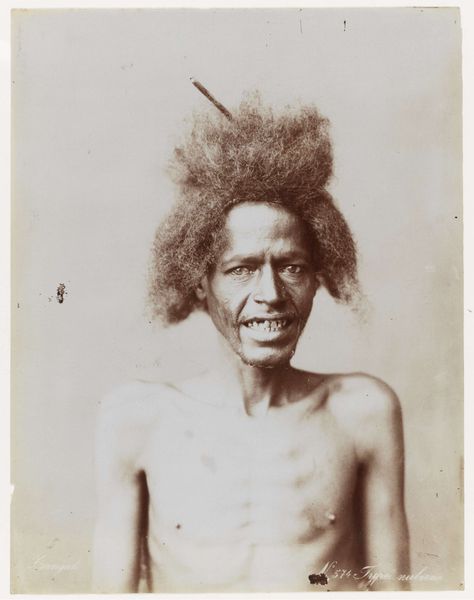

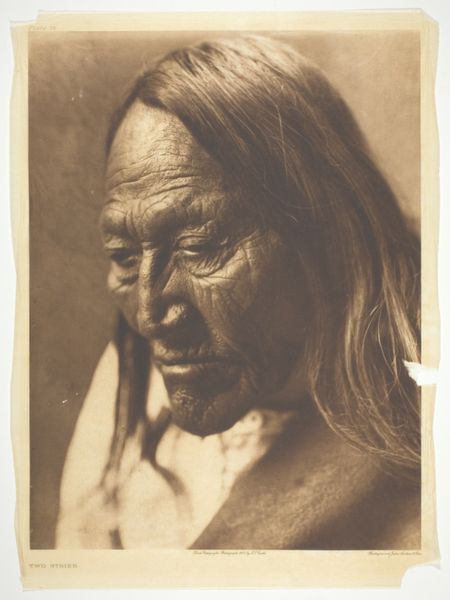

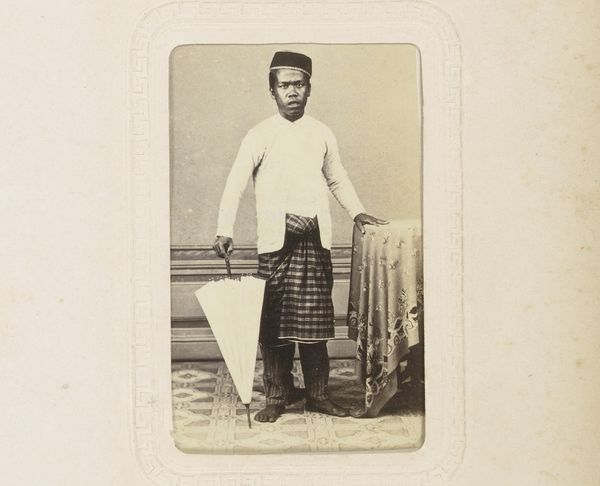

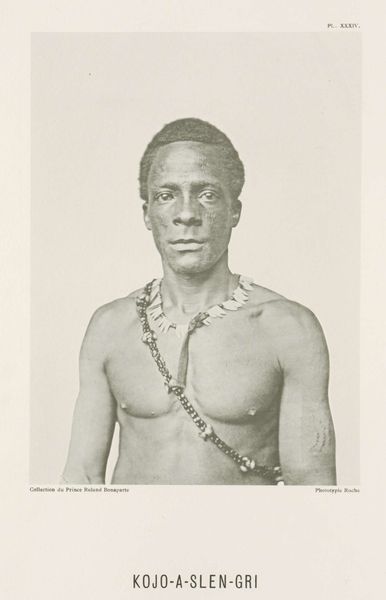

photography, albumen-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

orientalism

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 104 mm, width 63 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have a portrait, an albumen print dating from around 1870 to 1900, titled "Portret van een Maleisische man" - "Portrait of a Malaysian man." The starkness of the image really strikes me, particularly the direct gaze of the subject. What kind of story does this image tell you? Curator: Well, looking at this through a historical lens, the photograph instantly conjures up questions about colonialism and the “exoticization” of non-Western cultures. Photography in this period, especially these albumen prints marketed as "Orientalist" art, often served to reinforce power dynamics. It positions the subject as an object for Western consumption. Does this strike you as exploitative? Editor: It does, now that you mention it. The direct gaze seemed like a form of communication, but you're right, it could just as easily be a controlled performance. How did the rise of photography influence the visual language associated with colonialism? Curator: Photography offered a seemingly objective record, but these images were often carefully constructed. The sitter’s pose, the partial nudity, and even the printing process contributed to a specific, curated narrative of the “other.” Consider, too, how these images were disseminated – as souvenirs, in ethnographic studies, contributing to a wider, skewed understanding of different cultures. Did many people have their portraits done back then? Editor: Presumably only a limited portion of the population had access to photographic studios, or the means to participate in them. So the accessibility of that service must have been incredibly unbalanced depending on what people's backgrounds were, right? Curator: Exactly. Which brings us back to the question of who is controlling the narrative, and for whose benefit? Editor: It’s fascinating to see how a seemingly straightforward portrait can be unpacked to reveal so much about the socio-political landscape of the time. Curator: Indeed. It reminds us to look critically at visual representations and understand the power structures embedded within them.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.