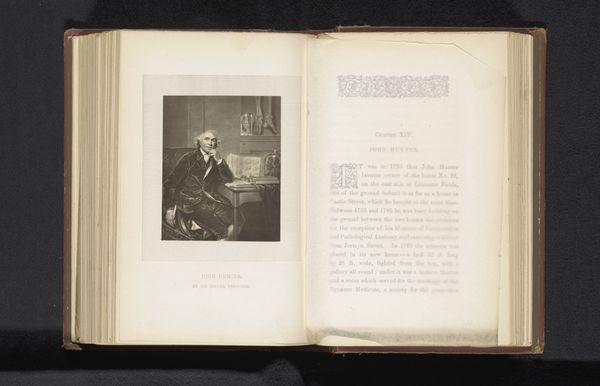

print, daguerreotype, paper, photography

#

portrait

# print

#

daguerreotype

#

paper

#

photography

#

coloured pencil

Dimensions: height 87 mm, width 68 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

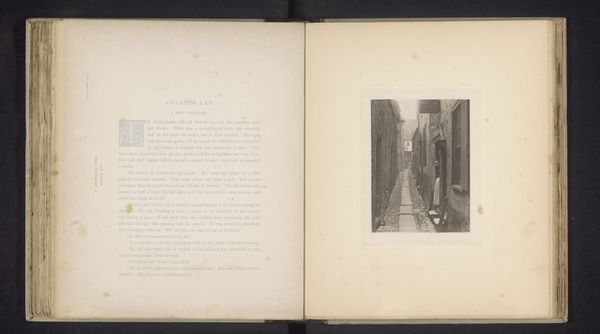

Editor: This is a fascinating portrait of John Obadiah Westwood, attributed to Ernest Edwards, and dating from before 1867. It's a print, possibly from a daguerreotype, and it’s adhered onto a book page, alongside some printed text about the sitter. There is a very formal, composed feel about this image... What do you see when you look at this portrait? Curator: The formality you observe reflects the conventions of Victorian portraiture, of course. But I’m interested in the implicit power dynamics embedded within images like these. Westwood is positioned as a scholar, seated at a desk, holding a book... a tool for the spread of enlightenment... or control, depending on one’s position. Who had access to such forms of representation? Whose stories were prioritized? The working classes were largely absent from such imagery. How do you think this piece speaks to issues of class and representation? Editor: That's a very interesting point. It makes me think about who has historically controlled the narrative. So, this image normalizes a certain level of society at the exclusion of others. How subversive was photography, though, back then, given painting's long history as a status symbol? Curator: Photography certainly democratized image-making to some extent. And yet, think about the technical expertise, the cost of materials, the social capital needed to commission a portrait like this. Early photography was not equally accessible. Further, photography could and still can be used to perpetuate harmful stereotypes and erase marginalized communities. Looking at Westwood here, he’s actively performing a certain identity, propped up by pose, prop, and the authority invested in learned men. Can you detect a dialogue about how photography in the mid-19th century began, even in its early days, participating in issues of gender and class that are still current today? Editor: It really makes me see that even something that appears to be a straightforward portrait is layered with so much cultural information about its time. I hadn’t really considered how class plays into who gets photographed. Curator: Exactly! It encourages us to consider how the photographic gaze and issues surrounding the photographic representation of people are as complex and multifaceted now as they were almost 200 years ago.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.