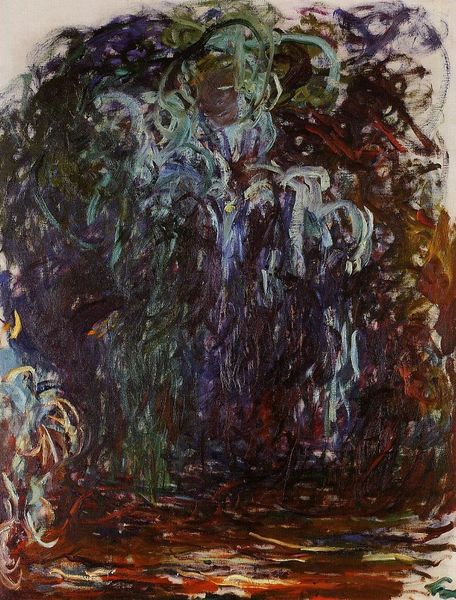

Copyright: Public domain

Editor: We're looking at Claude Monet's "Irises," painted in 1917. It’s an oil painting and when you stand in front of it, you can almost feel the texture of the paint. What’s fascinating to me is how he’s depicted the irises not as delicate blossoms, but almost as raw, growing matter. What do you see in this piece? Curator: What strikes me is Monet’s process here. We know he was working en plein air, immersed in his garden. Consider the labor involved: preparing the canvas, mixing the oil paints – pigments sourced, ground, and bound – a very physical engagement with materials and the land itself. The brushstrokes, so visible, they emphasize that act of making. Editor: That's a great point, the sheer effort involved in creating art like this, outside, in a garden… do you think the materials themselves played a role in how Monet depicted the irises? Curator: Absolutely. The viscosity of oil paint allows for layering, for building up texture. He's not just representing irises, he’s using the materiality of paint to convey the *experience* of irises, the feel of the leaves, the density of the flower. This was post-impressionism, remember – pushing against traditional representation. What kind of labour was necessary for this "experience" to become "high art?" Editor: It’s easy to get lost in the beauty of the painting, to forget the artist’s physical connection to it. I hadn’t considered the layers of production involved! Curator: Exactly. By examining the material realities – the land, the pigments, the brushstrokes – we can appreciate how Monet transformed common elements into a potent artistic experience. Editor: Thanks. Thinking about it this way helps connect the artwork to its cultural background and how much labour the art piece must have required to be realized.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.