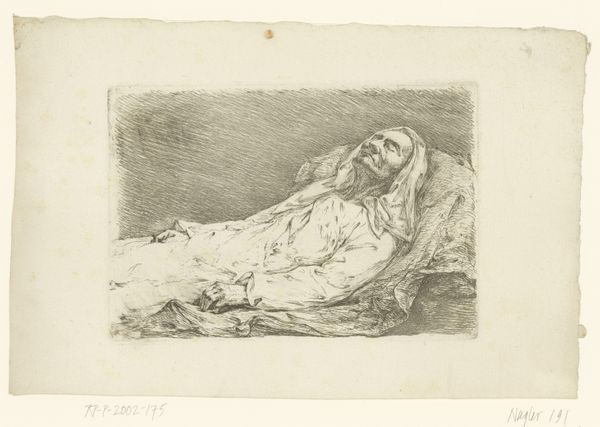

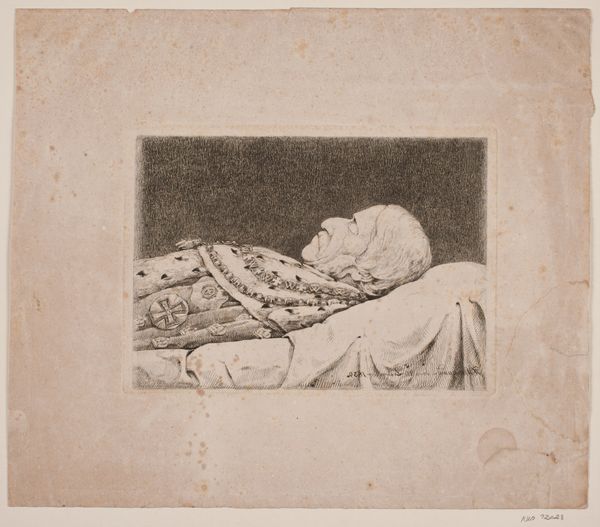

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

charcoal drawing

#

vanitas

#

pencil drawing

#

19th century

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 126 mm, width 194 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this print, the immediate impression is one of somber stillness. The sharp, delicate lines convey a palpable sense of finality and quiet contemplation. Editor: Indeed. This engraving, completed in 1870, captures “Advocaat François-David Picard op zijn sterfbed”—“Advocate François-David Picard on his Deathbed"—as rendered by Auguste Danse. It's currently held at the Rijksmuseum. It speaks volumes about the cultural fascination with mortality during the 19th century. Curator: Absolutely. The composition—Picard’s body prone, the meticulous details of the deathbed scene—lends itself to ideas around class, gender, and representation. How do images of death become these bourgeois displays, offering a visual memento mori for a certain public? Editor: Consider the setting: the subject, presumably a well-off advocate, lying peacefully with what appears to be a prayer book on his chest, set against the draped fabric that frames the bed. This resonates with broader narratives surrounding Victorian ideals of respectability, even in death. The very act of commissioning such a work underscores Picard's socio-political positioning. Curator: It makes me think about the power structures at play here, the male gaze inherent in this artistic rendering. Picard's death becomes a public performance, mediated through the artist's and ultimately, the viewer’s perspective. This image plays into notions of male authority and composure. Editor: I agree. And viewing it through a historical lens, consider the debates about secularism and religious faith present during this period. Picard’s positioning, almost devotional with the clasped hands, hints at his potential alignment with specific political factions. Curator: The darkness created with the dense lines of the engraving serves to create such intimacy in this very private and painful moment, that is then circulated and put on display. How do we grapple with such conflicting aspects of publicizing personal grief? Editor: These kinds of portraits, however morbid, are significant cultural artifacts. They demonstrate shifts in socio-political thought and the function of art within these broader conversations. Curator: Right, looking at it now, I appreciate how it provides not only insight into the past but also prompts discussion on enduring themes. Editor: For me, it exemplifies how artistic production acts as a powerful form of historical documentation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.