#

street view

#

sculpture

#

possibly oil pastel

#

oil painting

#

unrealistic statue

#

coloured pencil

#

underpainting

#

painting painterly

#

3d art

#

watercolor

Copyright: Public domain

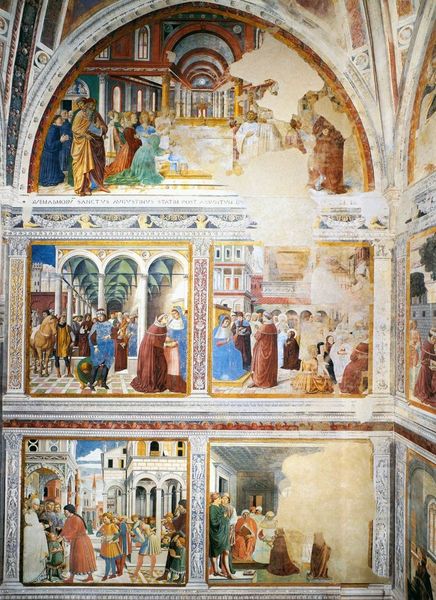

Curator: At first glance, this piece plunges you into some kind of epic drama, but with an ethereal touch. It feels almost dreamlike. Is it me, or does the whole scene have a kind of otherworldly glow about it? Editor: What grabs me first is how this work by Antoniazzo Romano, “Stories of the Holy Cross,” dated to 1492, weaves together visual narrative and socio-political meaning, a common trend during the Renaissance. The choice to depict scenes from the legend of the True Cross provided not only religious instruction, but it also reinforced specific social and political ideals dominant at the time. Curator: Absolutely, I see that now. So much going on—armored figures clashing with a cross held high, like some ancient parade about to burst right into a war zone. Is that supposed to be the Holy Cross leading these guys, like some divinely powered weapon? It's a bold statement, that’s for sure. Almost militant in its message. Editor: It's a narrative strategy. Paintings like this acted as powerful tools, reflecting contemporary events and justifying existing power structures. The figures, though idealized, suggest a direct connection between divine will and earthly affairs. Imagine, back then, witnessing such a spectacle. What could that mean to the illiterate and most vulnerable citizens of Rome? Curator: Yeah, I guess art in those days really did a lot more than just hang on walls. I find myself drawn into the detail – each tiny figure caught in a moment of either fierce attack or peaceful resilience. Plus the contrast of the soft sky set against the intense human actions. Makes the divine influence almost tangible. You can practically feel that holy gust blowing through the painting, altering the courses of these earthly happenings. It feels more like theater than just pigment and canvas. Editor: And that's precisely the intended effect. Religious confraternities or wealthy families commissioned such artwork for churches and chapels to highlight their piety, legitimize their influence, and align their narrative with stories from the Christian imaginary. This fusion of religion, politics, and personal legacy offers an intimate glimpse into Renaissance society, reflecting on issues of faith and governance. Curator: Well, stepping back from it, what an interesting time to create. Bridging a belief with a visual representation of dominance is not something you find every day. So yes, you can learn a lot from just an image! Editor: Indeed. A vibrant illustration from centuries ago showing us that faith can be a complex force in social change.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.