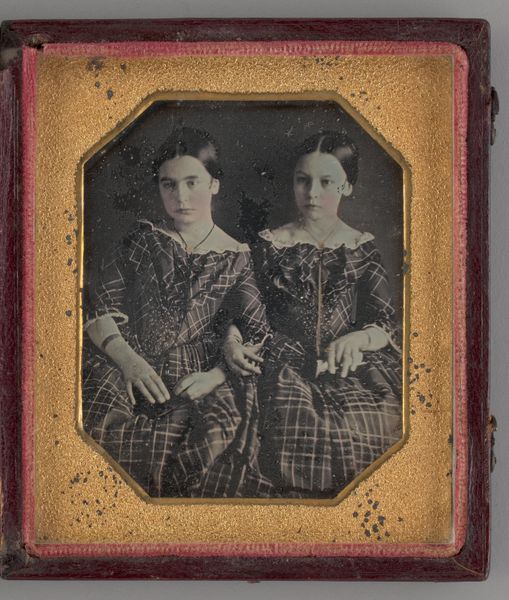

Dimensions: 7 × 8.3 cm (2 3/4 × 3 1/4 in., plate); 9.1 × 16.2 × 1 cm (open case); 9.1 × 8 × 1.8 cm (case)

Copyright: Public Domain

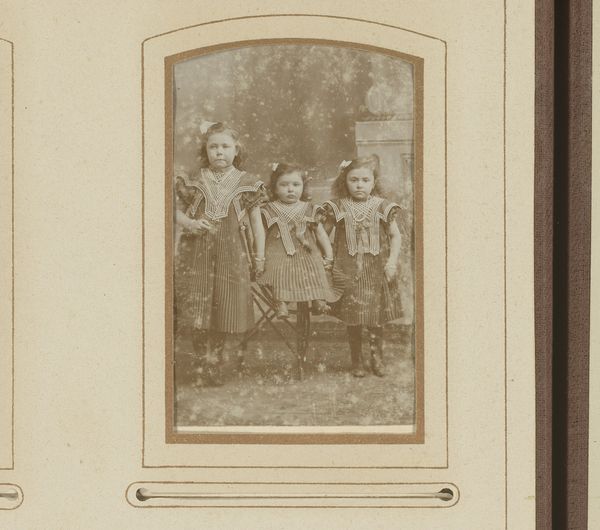

Curator: Looking at this, the immediate impression is solemnity; such serious young faces. Editor: This is an untitled daguerreotype dating from 1858, now held at The Art Institute of Chicago. It portrays a young girl flanked by two boys. Curator: Absolutely. The staging and composition speak to the burgeoning genre of portraiture for everyday people, though this work is a little different. Given photography's long and problematic relationship with gender, race and class, do we know anything about their socio-economic position? Are there any clues for reading these children outside a simply romantic or even genre framework? Editor: Indeed, without firm information on the sitters, such things can only remain suggestions; we may only read meaning into it through modern theoretical perspectives. Yet it's true: the stark directness, unusual at a time where more soft and allegorical presentation of childhood prevailed, brings to mind the emergence of Realism within artistic practice. The photographic clarity is interesting as a moment where Realism becomes newly enabled. This contrasts dramatically with the artifice apparent in how the work came to be situated and thus circulated and viewed, bound within such elaborate cases to ensure preservation. These photographic images were expensive at the time, implying a certain status, especially considering they had multiple children photographed. Curator: It's true that the materiality gives us one context, however it's important to ask, whose stories do these photographic practices typically conceal? Did such portraiture allow for the visual recognition and representation of subjects historically excluded, especially working class children and children of color, and do the children's unsmiling expressions challenge idealized depictions? Editor: The daguerreotype as a medium certainly played a vital role in the dissemination of imagery during that period. Though initially expensive, photographic reproduction allowed an unprecedented access for the public. As we view it today, the frame acts as a subtle reminder about historical class and economic divides within society at the time. But for the middle classes, it provided lasting memories within rapidly changing times. Curator: Right, reflecting on this image, the expressions still capture my imagination—what was it like to exist in their world? How might understanding this time alter current discourses of representation and childhood? Editor: Exactly. Considering the public perception and socio-political effects that emerged from visual culture—particularly how quickly the technology developed—certainly creates an imperative for modern consideration.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.