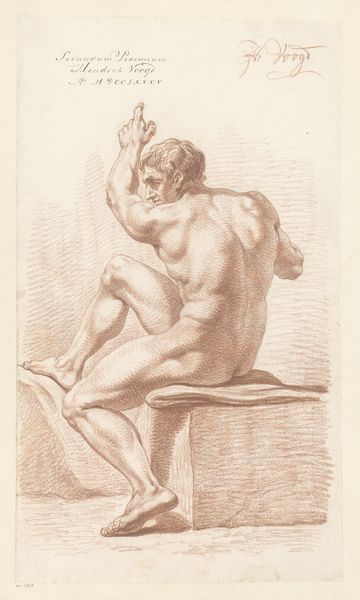

drawing, dry-media

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

figuration

#

dry-media

#

pencil drawing

#

portrait drawing

#

pencil work

#

academic-art

#

nude

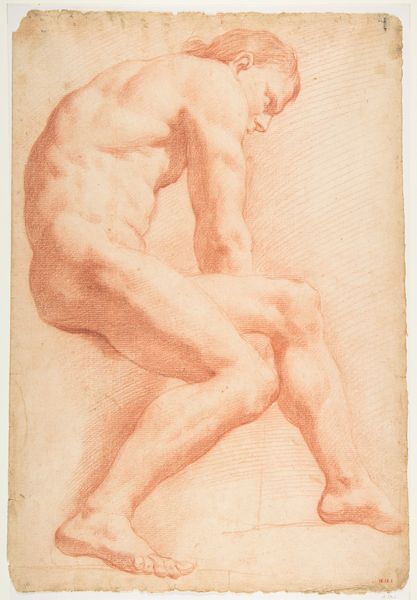

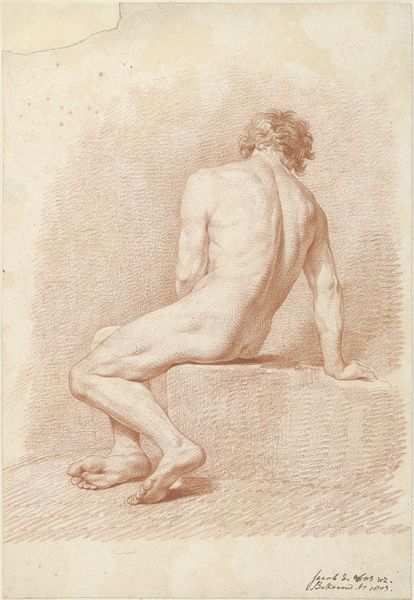

Dimensions: height 595 mm, width 452 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

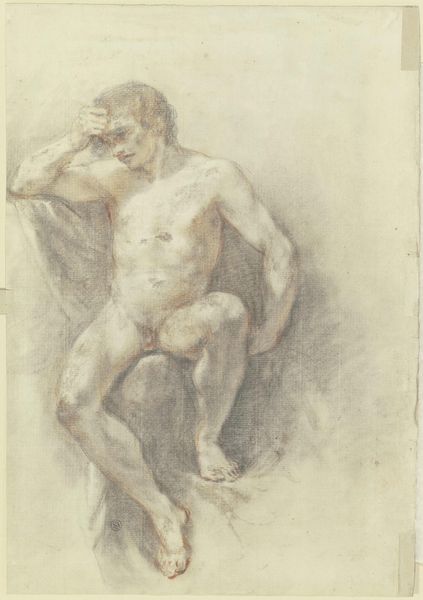

Curator: Here we have "Zittend mannelijk naakt", or "Seated Male Nude," a drawing created by Cornelis Joseph d' Heur sometime between 1717 and 1762. It is done with dry media, likely pencil, on paper. Editor: It feels academic, a study perhaps. The sitter’s pose, the angle of his head—everything seems to point inward, a thoughtful solitude. The reddish tone adds warmth, but there's also a certain melancholy in the downcast gaze. Curator: Yes, the classical contrapposto and the artist's technique reflect academic art practices common during the Baroque era, prioritizing anatomical accuracy and idealized form. But note how the paper itself bears witness to its creation—the material reality of artistic labor made evident. Editor: Indeed. The linear precision in defining muscle and bone strikes me, and the carefully hatched shading evokes a sculptural presence, alluding to depth and volume within a two-dimensional framework. I can almost feel the texture of his skin and the rough surface of whatever he's seated upon. Curator: Consider, also, the social context: this wasn't just about aesthetic pleasure. Nude studies were crucial for artists to master human anatomy, and that proficiency was essential for creating historically and mythologically themed paintings for wealthy patrons, paintings which reinforced prevailing power structures and narratives. The drawing, a functional object and a step in a much broader production chain. Editor: Precisely, and consider d' Heur’s use of color and light! He deftly directs our eyes, structuring the entire composition. His careful build-up of shadows and highlights emphasizes musculature, drawing my attention across the paper. Curator: In that time, even the 'raw' materials spoke volumes, didn’t they? Paper sourced from particular mills, pencils with carefully regulated graphite content… each decision embedded in a matrix of material supply chains, economic power, and cultural preferences. Editor: I see your point. Yet beyond the labor, context, and materiality, I perceive something deeper: the sheer artistic ability and its timeless quality—capturing not only physical form, but also an essential facet of the human condition. Curator: Perhaps that intersection between tangible making and something just beyond our grasp—a meeting point for formal design and lived reality—is precisely what makes such pieces resonate centuries later. Editor: It certainly offers a way to connect with a sensibility distant, but somehow, still so present.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.