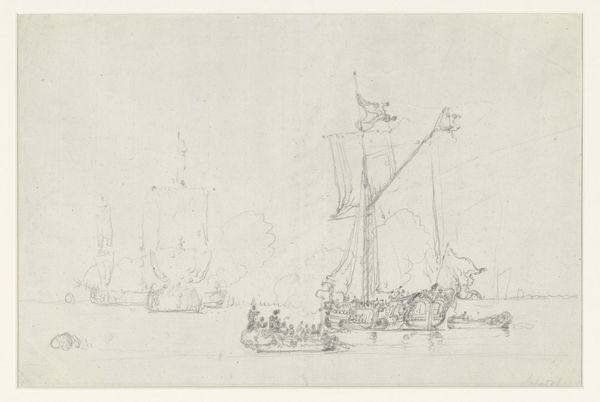

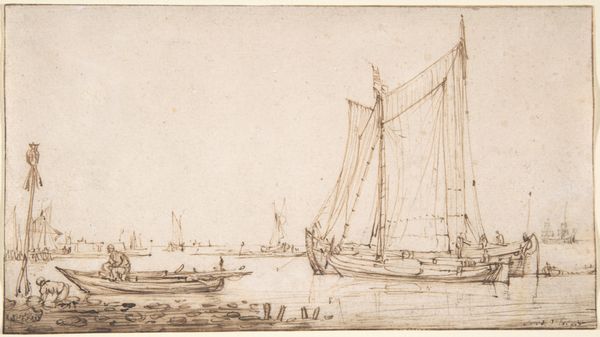

Dimensions: height 172 mm, width 248 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let's discuss "Lossen van aangemeerde schepen," or "Unloading of Moored Ships," a work created between 1767 and 1780 by Bernhard Schreuder. It resides here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My immediate thought is "ghostly." It feels like peering into the past through a veil. The lines are so delicate, the details are muted. Curator: That muted quality arises from Schreuder’s primary materials: pencil and ink. It is quite representative of Dutch Golden Age genre painting and landscape traditions, but rendered with an emphasis on line. How does that affect our perception of the scene? Editor: I think it underscores the labor aspect, frankly. You see these figures—seemingly anonymous, certainly without aristocratic pretense—wading, carrying, bending. It highlights the social strata reliant on unseen workers, whose efforts are often marginalized in favor of celebrating the grandeur of mercantile success. The drawing shows its mechanics of wealth creation. Curator: It's interesting that you pull that out; often in readings of art from the period the emphasis falls primarily on commercial exchange rather than labour. Given it captures the moment goods are moved from ship to shore, a point of global connection is materialized and also immediately decentralized to multiple laborers. Editor: Exactly! And if we apply contemporary theory, it begs the question: whose history gets foregrounded? Whose bodies enable the narratives we typically consume? How are global supply chains implicated, even at this moment captured by Schreuder? These are still central questions now. Curator: So, the aesthetic choice of a simple drawing ends up creating a potent image that resonates across time, even if, during the Dutch Golden Age, such scenes might have been viewed through the lens of prosperity alone. Editor: Ultimately, I think by drawing our attention to the unloading, to the laborers themselves, he provokes a certain social awareness of the mechanisms behind Holland's shipping trade. It serves as a critical intervention in what’s seen, and who is usually left unseen. Curator: I appreciate how you have encouraged me to pause and really consider the politics imbued into this drawing and how they intersect across time periods. It is far more than simply just a quaint harborside view.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.