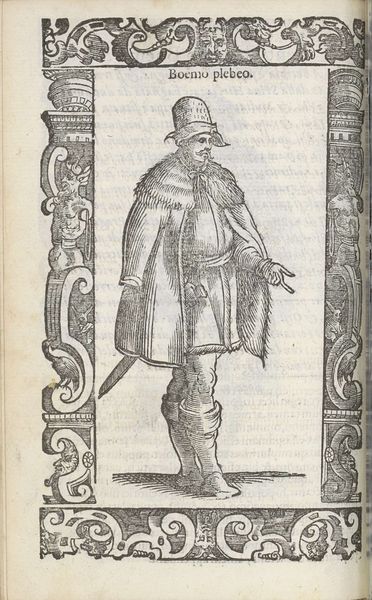

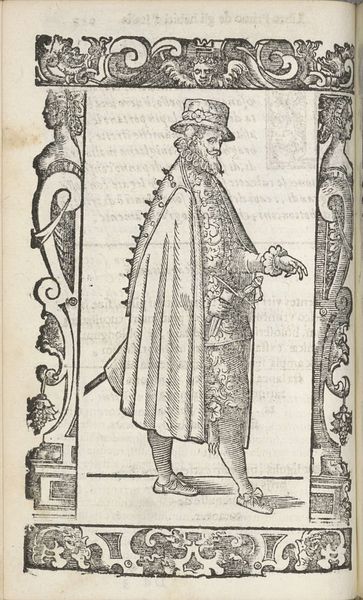

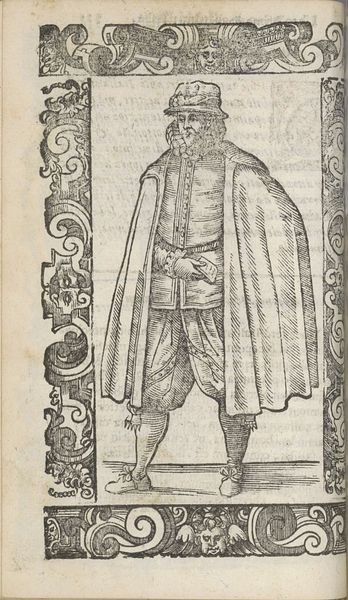

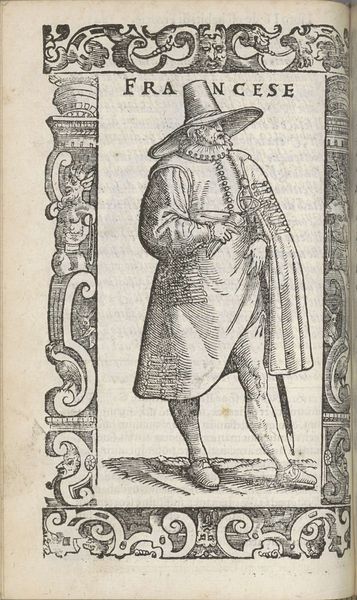

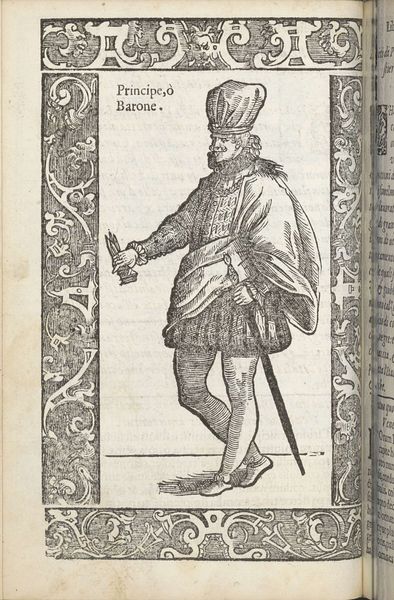

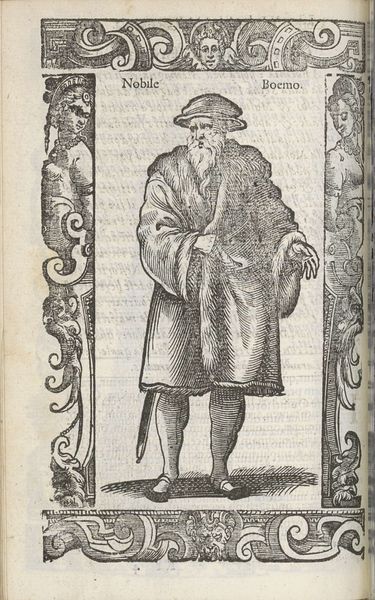

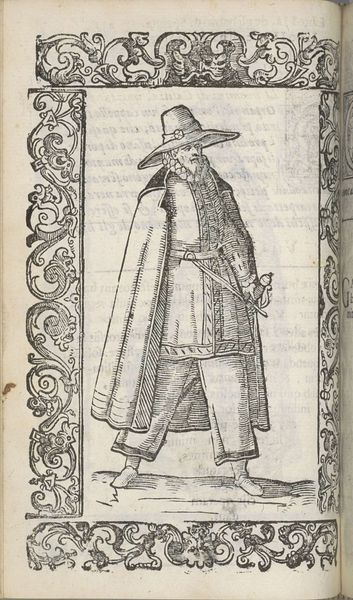

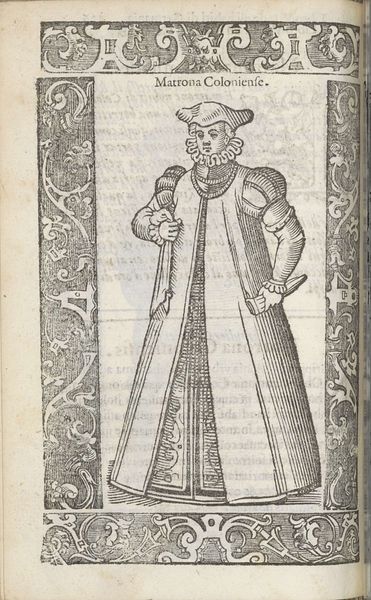

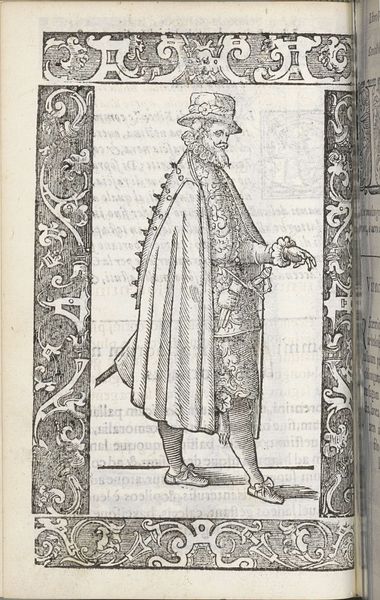

engraving

#

portrait

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

line

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 167 mm, width 125 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have "Primo di Magistrato," an engraving by Christoph Krieger from 1598. It's this striking black and white portrait, full of detail. What's particularly interesting is how this image, originally intended for a book, takes on a life of its own. What do you see when you look at this work? Curator: I immediately consider the process behind creating this print. Think of the labour involved. The artist had to meticulously carve every line into a metal plate. This wasn't just about aesthetics; it was about reproducing and disseminating knowledge, or promoting the figure represented. The materials themselves--the metal, the ink, the paper--speak to the economic and social structures of the time. The relatively small scale also indicates this image was made for book, where dissemination of ideas would have been very popular. Editor: That’s fascinating! I hadn’t really thought about the actual work that goes into creating something like this. So, are you saying the materials used for distribution hold as much meaning as the subject portrayed? Curator: Precisely. This wasn't simply about immortalizing someone. The choice of engraving speaks to a specific mode of production, one that democratized images but also demanded skilled labor. We should consider the workshops where these prints were made and the networks through which they circulated. What type of person would have possessed such an image? Where would they store it? And how does our perception of this change when its context goes from an individual with a book to thousands around the world who have access to this digitally? Editor: So, it's like considering not just the "what" but the "how" and "why" it was made that truly unlocks the work's meaning. The process and intention become just as crucial as the final product. Curator: Exactly. Understanding the materials, labor, and distribution allows us to see this portrait as a complex product of its time, deeply intertwined with the social and economic forces at play. I hadn’t thought about the modern adaptation of its context; interesting point!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.