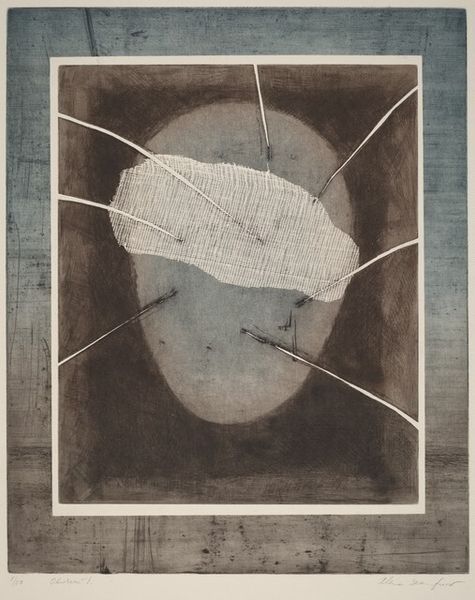

Dimensions: image: 996 x 695 mm

Copyright: © Richard Deacon | CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED, Photo: Tate

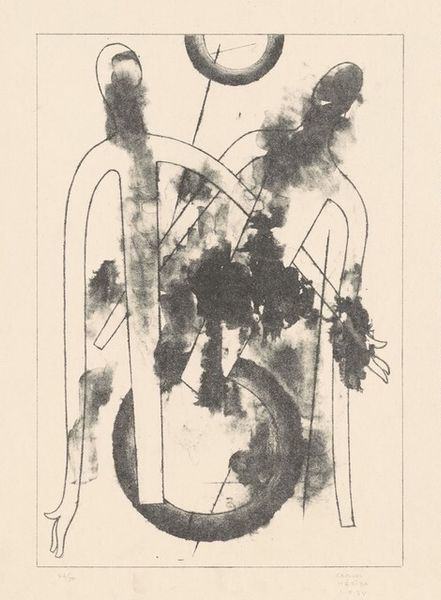

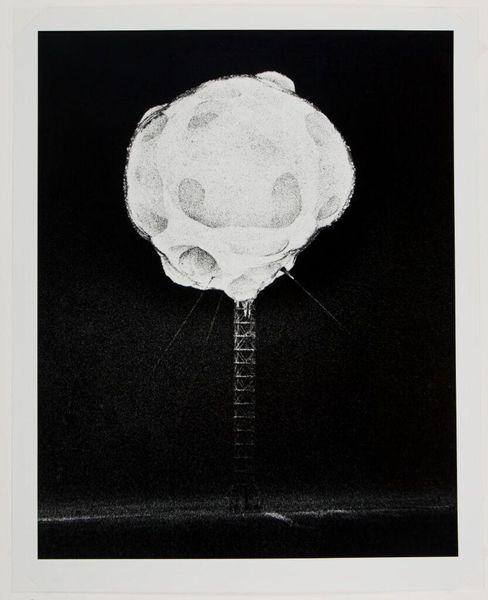

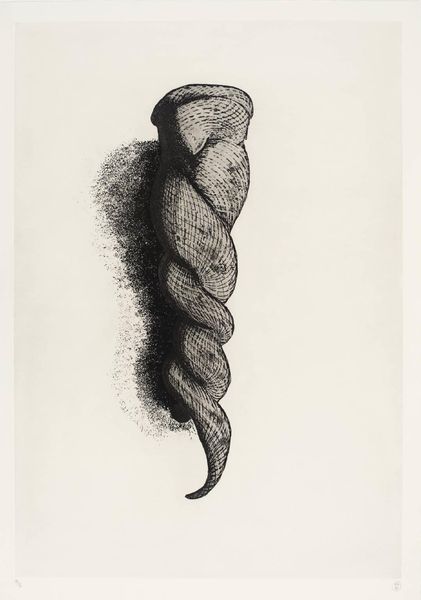

Curator: Richard Deacon's print, "A Curious Carrot," immediately strikes me as something melancholic, despite the somewhat humorous title. The textures are so dense! Editor: Indeed. Deacon, born in 1949, is well-known for challenging conventions. He trained first as a goldsmith. He then shifted to sculpture, and this print exemplifies his interest in materiality. The juxtaposition of textures is compelling. Curator: Absolutely. The contrast between the soft, almost cloud-like background and that solid, almost industrial-looking base is striking. How do you see its role within the context of printmaking traditions? Editor: Well, printmaking in the late 20th century was undergoing something of a revolution. Artists were really pushing the boundaries of what could be considered fine art versus craft. Deacon, with his focus on process, was part of this. Curator: It certainly prompts us to consider the labor involved in its creation. The cross-hatching suggests a laborious process. Editor: I concur. "A Curious Carrot" encapsulates Deacon's ability to imbue the commonplace with a profound sense of materiality and the weight of production. Curator: A beautiful way to put it. And now I will never look at a carrot the same way again!

Comments

tate 10 months ago

⋮

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/deacon-a-curious-carrot-p11442

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.

tate 10 months ago

⋮

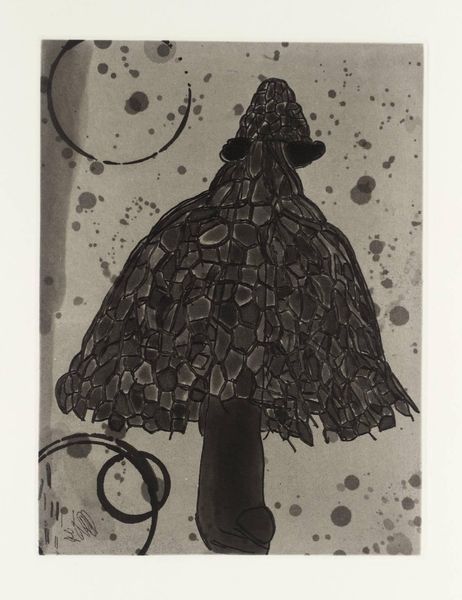

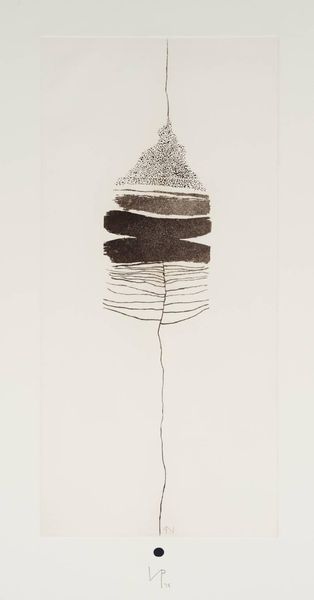

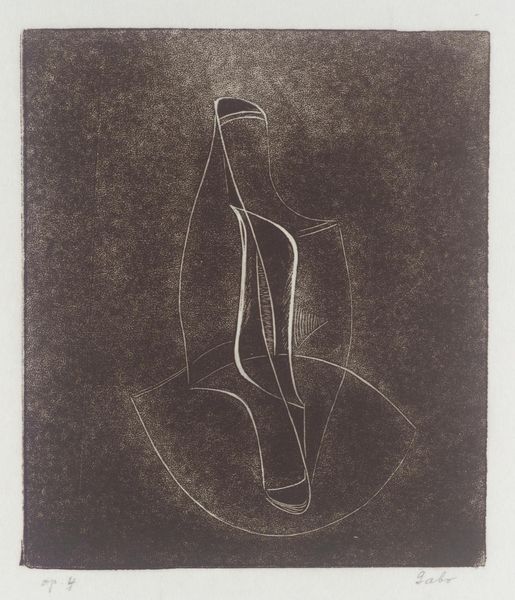

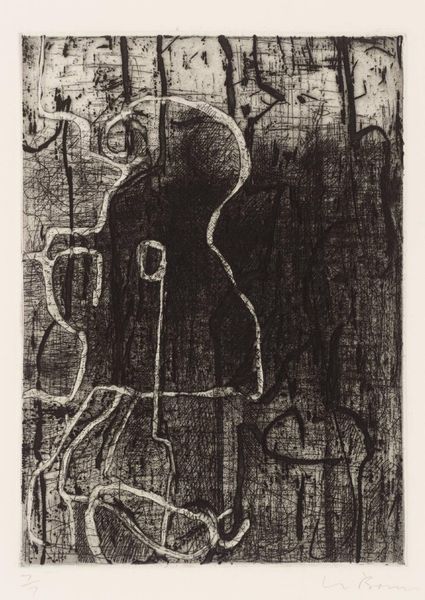

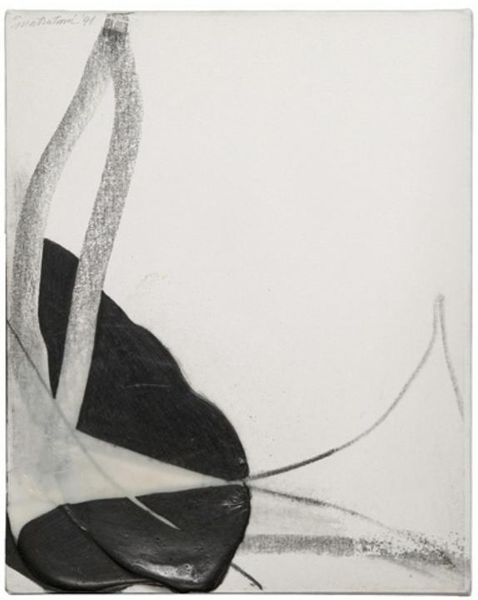

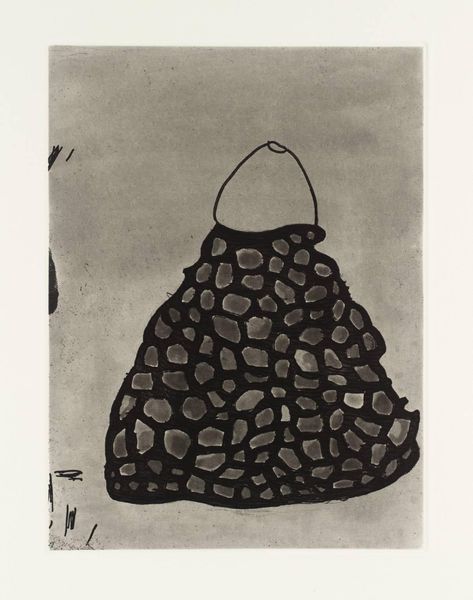

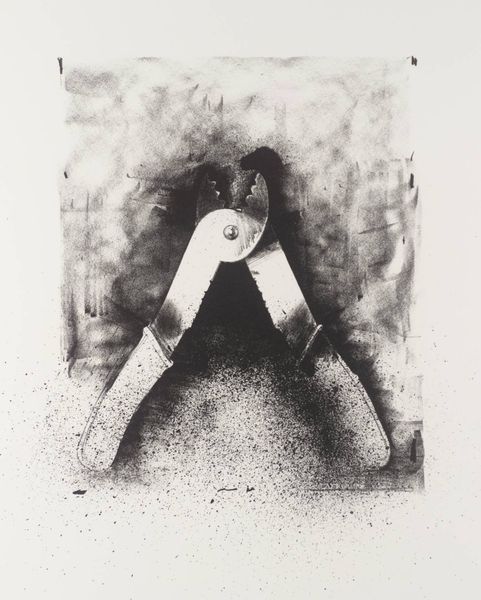

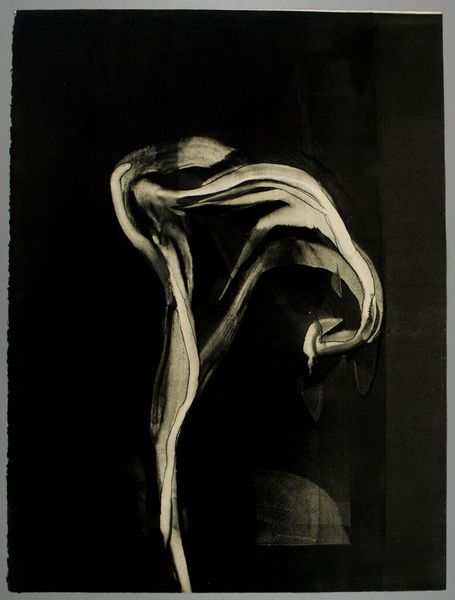

A Curious Carrot is one of a set of five intaglio prints in an edition of twenty-five that are collectively titled Curious. Primarily a sculptor, this portfolio constitutes Richard Deacon's second foray into printmaking and was embarked upon some four years after he produced his first series of prints, Muzot in 1987 (Tate P77252-P77255). The other four prints in the set are titled A Curious Potato (Tate P11441), A Curious Apple (Tate P11443), Another Curious Potato (Tate P11444) and Another Curious Carrot (Tate P11445). The etchings are based on the artist's childhood memories of photographs reproduced in the Strand magazine of the 1880s. Deacon's grandmother had a set of bound copies that he and his siblings would pore over for hours on end. The magazine featured photographic portraits of leading public figures, as well as amateur photographs of vegetables whose strange shapes recall human features. In an unpublished text of 1995, Deacon described how, over time, his recollection of the vegetable imagery had become distorted: I remembered the pictures of the vegetables, but recalled them as studio pictures, portraits on a par with the pictures of famous Victorians - people whose names I didn't recognise with a lot of hair. It was a false memory, the pictures appeared on the readers letters page, were small and poorly reproduced. They are interesting evidence of the extent and spread of amateur photography but certainly not the grand portraits they had become in memory. When the publisher, Margarete Roeder, invited Deacon to produce another set of prints with her (she had published Muzot in 1987), he chose to develop this misrecollection and produce images which would conflate the two types of photographs he found in Strand magazine. The prints are large portraits of oddly misshapen vegetables and fruit, whose humanoid features are frequently emphasized by accompanying props. For example, A Curious Potato resembles a bulbous face wearing a tall hat, while Another Curious Potato depicts a bent figure leaning on a walking stick. A Curious Carrot and A Curious Apple sit atop objects identified by Deacon as an eggcup and a hammered metal flask respectively. The last in the series, Another Curious Carrot, is the only one where resemblance is not a concern. For Deacon, its evocative form is suggestive of entwined lovers, winding sheets or, even, the entangled figures of Indian sculpture. Deacon used a variety of procedures to produce each print. He began by making drypoints, which were reprographically enlarged to the size of the largest plates available in the studio. The resulting line images were cleaned and edited before being used as the source for a photoetching onto the large plates. Deacon then used aquatint and spitbite to reintroduce modulation into the lines and to provide backgrounds for the images. The series was printed by Peter Kneubuhler and Peter Stiefel at the Atelier Peter Kneubuhler in Zurich. It was published by Margarete Roeder Editions in New York. Further reading:A Quiet Revolution: British Sculpture Since 1965, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago 1987.Jon Thompson, Pier Luigi Tazzi and Peter Schjeldahl, Richard Deacon, London 1995.New Art on Paper, exhibition catalogue, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia 1996, p.30-31, reproduced p.31. Helen DelaneyNovember 2001