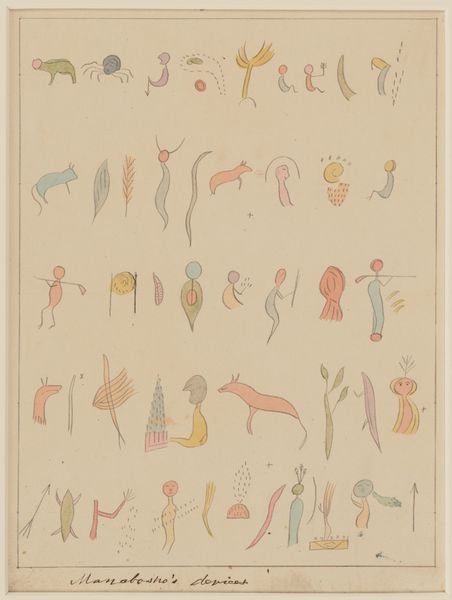

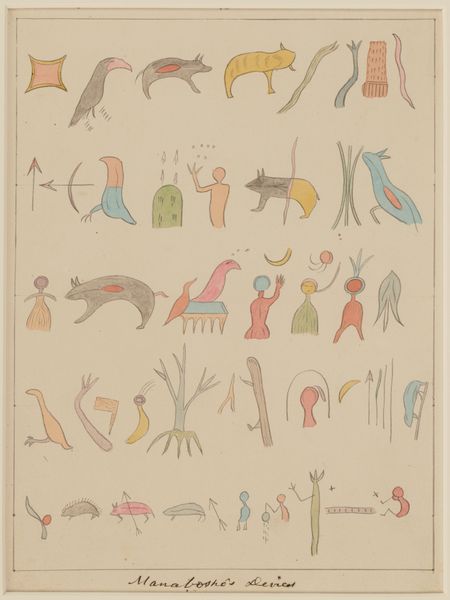

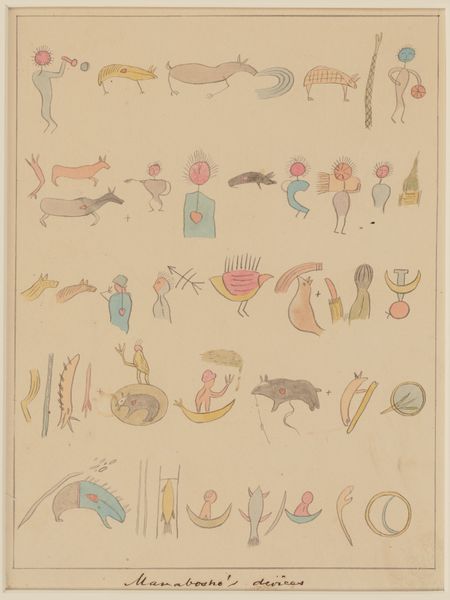

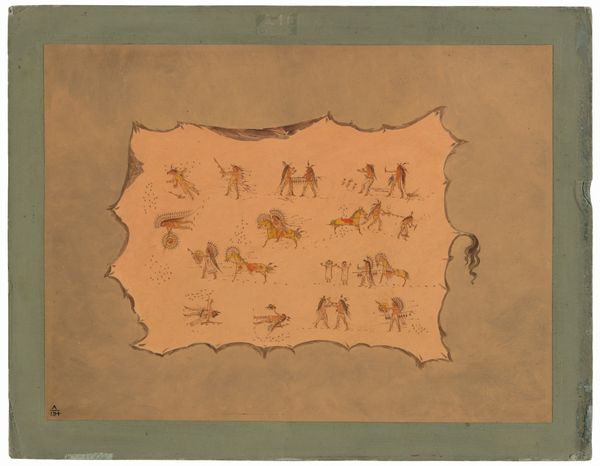

drawing, coloured-pencil, paper, pencil

#

drawing

#

coloured-pencil

#

narrative-art

#

paper

#

pencil

#

indigenous-americas

Dimensions: 8 15/16 × 6 3/4 in. (22.7 × 17.1 cm) (image)9 5/8 × 7 1/2 in. (24.4 × 19.1 cm) (sheet)21 1/2 × 17 9/16 × 1 1/8 in. (54.6 × 44.6 × 2.9 cm) (outer frame)

Copyright: Public Domain

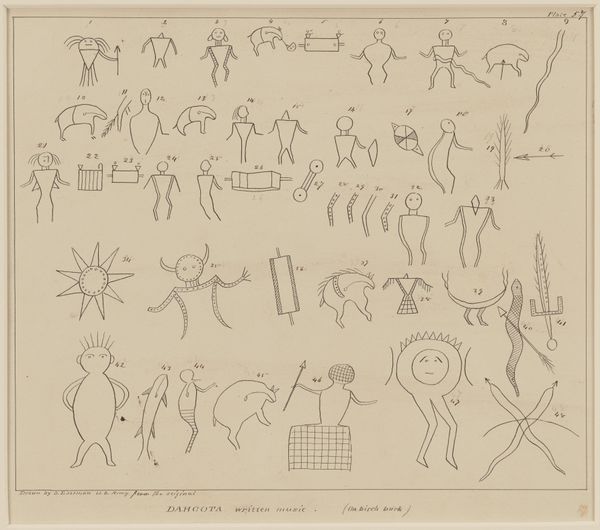

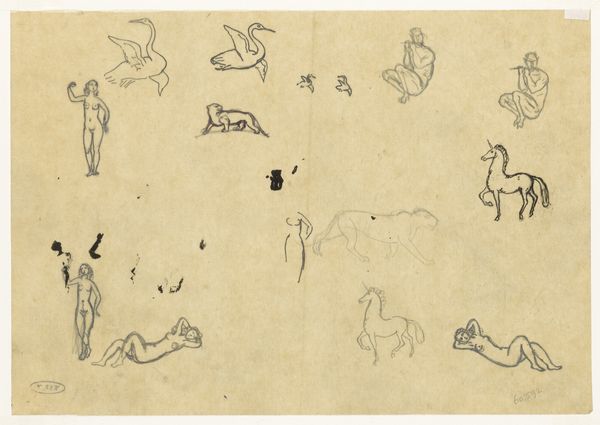

Curator: Welcome to the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Today, we'll be discussing "Manabosho's Devices," a drawing made between 1849 and 1855 by Seth Eastman. Eastman, an American soldier and artist, is known for his depictions of Native American life. Editor: My first impression is of a beautifully sparse composition. The muted colors and primitive shapes evoke a sense of the archaic, like early cave paintings but rendered with a gentler hand. Curator: Indeed. This work offers insight into the cultural exchanges happening during that period. Eastman's position afforded him access and opportunity, even as the socio-political context involved westward expansion and the displacement of indigenous peoples. Editor: Structurally, I'm struck by the arrangement of the figures; they float on the page with no ground, no horizon. This isolates each element, inviting a prolonged focus on its form and symbol. It’s a tableau of the mind, unbound by reality. Curator: Eastman's choices regarding materials are telling. Drawings allowed for a relatively immediate documentation of his encounters with the Dakota people. Here he presents narrative-art concerning Manabosho. Editor: There's a naive quality to the rendering that softens its impact. It’s as if we’re viewing complex concepts through the eyes of a child, where simplified forms can contain whole universes of meaning. The slightness in each stroke renders its themes that much more intimate. Curator: It raises the crucial question of representation. As a non-native artist, Eastman's interpretation and mediation significantly shape how we understand these symbols. The 'devices' might be viewed by a society such as the Dakota people as an oral or societal tradition not easily documented as images on the flat page. Editor: Thinking about how lines and color can act as linguistic tools makes this so enticing. The repetition of shapes creates a rhythm and a sense of interconnectedness, each motif resonating against the neutral ground. It pulls you back in and reveals its story anew. Curator: By studying it, we also examine the dynamic between those recording and those being recorded, acknowledging the power imbalances and the responsibility of interpreting such imagery with care. I value the potential for such drawings to ignite discussion. Editor: Absolutely. Ultimately, this piece captivates with its strange visual economy and beckons us to untangle and consider all its implications.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

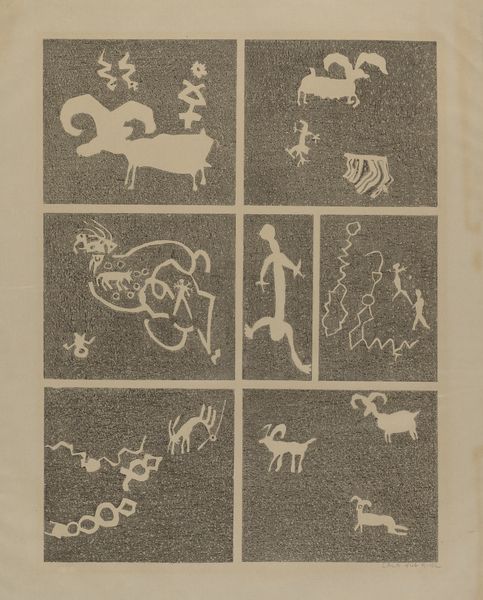

Henry Rowe Schoolcraft reportedly collected these pictographs, which he named for the mythic Ojibwe character Manabosho, around Lake Superior. Although it is unclear how accurately the pictographs were transcribed, they were intended to describe a story, chant, or historical event. Seth Eastman painted four sheets of pictographs as the basis for the illustrations in Schoolcraft's "Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States" (1851-57), and these original watercolors are among the 35 works on paper by Eastman in Mia’s collection.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.