Copyright: Public Domain

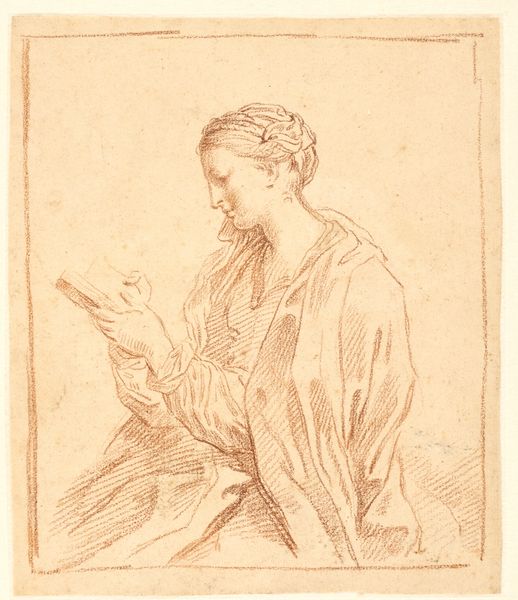

Editor: This pen drawing, “Portrait of a Donor’s Wife” by Matthys van den Bergh, was created around 1530. I find it intriguing that the portrait, seemingly so personal, is rendered with such visible marks of the artist's hand and tools. What does this choice of process tell us? Curator: Indeed! Consider how the very act of drawing, the labor involved in its creation, directly reflects on the social standing of both the sitter and the artist. Pen and ink drawings, while less costly than painted portraits, still involved a specific level of skill and access to materials. Editor: So, even the medium suggests something about class and consumption? Curator: Absolutely. This isn't just an image; it's a material object made through specific means of production that inherently ties into social hierarchies. Note how the details of her garments are carefully delineated, suggesting the quality of the fabric and the artistry of its creation – highlighting, materially, her status. Editor: That's fascinating. The labor behind creating both the portrait and the clothing within it contributes to our understanding of her world. Was drawing common for portraiture at the time? Curator: Drawings served various functions. They could be preparatory sketches for larger paintings, independent works of art for a select clientele, or even used in printmaking for wider distribution, again linking material production to consumption and accessibility. In examining this piece, what statements does the patron wish to make with such careful detail? Editor: It brings a new perspective, thinking about the piece not just as art, but as a material document shaped by labor, materials, and even the economic landscape of its time. Curator: Precisely! By investigating the 'how' of its making, we reveal insights into the 'why' of its existence and the world that shaped its creation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.