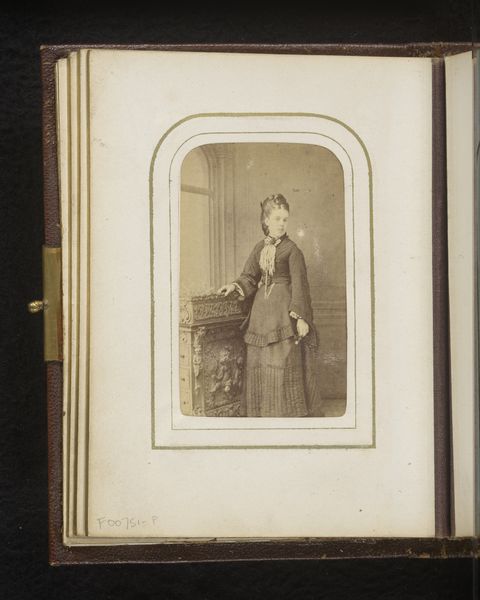

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

book

#

figuration

#

photography

#

coloured pencil

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: height 84 mm, width 52 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this piece by Amédée Denisse, titled "Portret van een zittende vrouw met muts en boek in de hand," a gelatin-silver print dating from 1850 to 1867, what strikes you? Editor: Immediately, I'm drawn to the fabric of the woman's dress. The way the light catches and folds, it speaks to a specific material and the labor involved in its production. Curator: Precisely. And how does that reading impact your broader understanding of the artwork within its socio-historical context? This portrait speaks volumes about gender roles and societal expectations during that time. The woman’s demure posture, her attire, the very fact she is captured with a book—all reflect the prescribed sphere for women in mid-19th century society. The photographic act itself became a way for some women to assert their identities within very strict confines. Editor: Absolutely. I see the book as a critical component. The photograph becomes a document of access to knowledge, and the materials involved, from the paper to the ink, become extensions of the woman's intellectual world, as if education is another layer of textiles. Also, consider the photograph’s materiality—the specific gelatin-silver process—reflects evolving technologies and emerging industrial practices. Each choice—the paper, the chemicals, the printing—speaks to the economic realities underpinning artistic creation. Curator: That's an interesting interpretation of access. Also consider that while photographic technologies may seem democratizing, early portraiture remained relatively exclusive, affordable primarily to middle and upper classes. Therefore, understanding the socioeconomic framework of artistic production, including photography, unveils complexities regarding visibility, power, and representation. The portrait thus offers not just an image of an individual but also invites inquiries concerning the privileges and constraints experienced by women of her status. Editor: I agree. And the scale matters too, doesn’t it? It's an intimate portrait, made for a specific, possibly private, purpose. A treasured object, like her book. Thinking about the physical handling, the consumption... this photograph probably lived a very different life than a painting displayed on a gallery wall. Curator: Exactly, the physicality adds to our perception of the work. Studying this portrait encourages critical interrogation regarding gender, class, and the materiality of art. Editor: Yes, from thread to text, ink to emulsion, it invites a multilayered conversation about representation and social reality.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.