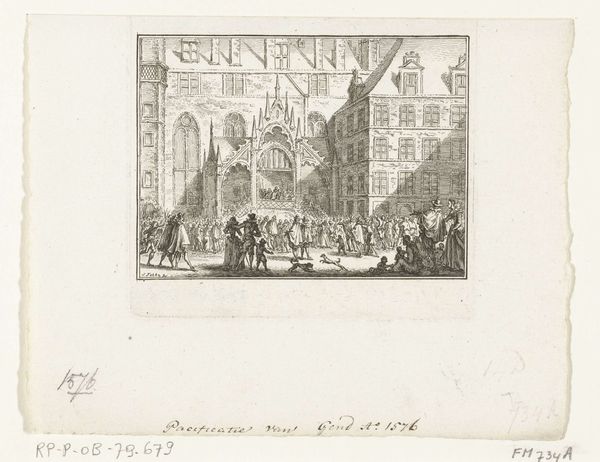

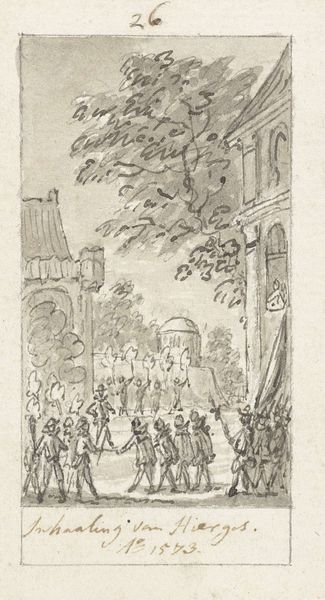

De Sint-Bavokerk in Haarlem bestormd door protestanten, 1578 1782 - 1784

0:00

0:00

simonfokke

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 90 mm, width 106 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So this engraving by Simon Fokke, made between 1782 and 1784, depicts ‘De Sint-Bavokerk in Haarlem bestormd door protestanten, 1578’. It shows quite a chaotic scene. What do you see when you look at it? Curator: Immediately, I see the labor involved. Think about the engraver painstakingly cutting into a metal plate to create this image, reproducing a historical event. The means of production dictate a certain visual style—fine lines, detailed rendering, but also a distancing from the raw emotion of the event itself. It becomes a commodity, an object of consumption for a 18th-century audience. Editor: Commodity, yes! It's odd to think of something violent, like a church storming, being consumed as art. Curator: Exactly! And consider the materials: ink and paper, widely accessible by the late 18th century. How does the artist translate this tumultuous historical moment, fraught with religious and political significance, into something easily reproducible and marketable? Editor: Is it almost trivializing the event by making it a commercial object? Curator: Perhaps, or perhaps it's about controlling the narrative. By framing the event, turning it into a discrete image, you domesticate it, make it understandable, digestible. It’s a deliberate act of ordering chaos. Editor: That's really interesting. So, instead of just focusing on the image itself, we can see it as a material product reflecting the social context in which it was made? Curator: Precisely! The print becomes evidence of not just the event depicted, but also the values and material conditions of its production in the 18th century. We can ask questions like who consumed these prints, and what purpose did they serve. Editor: Wow, I’ll never look at engravings the same way again. It's not just the history in the image, but the history of the image itself as an object. Curator: That's the beauty of a materialist approach: unveiling the layers of meaning embedded within the artwork’s physical existence.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.