Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

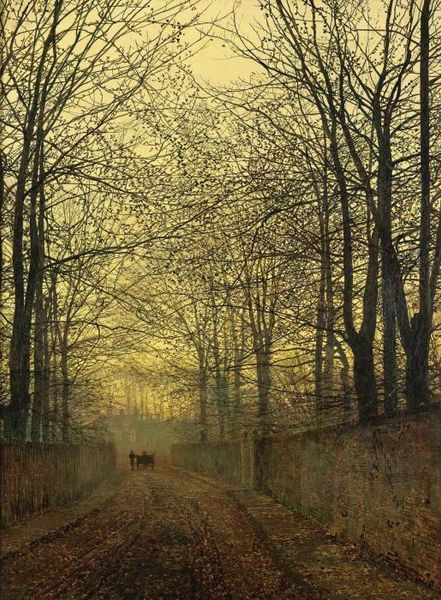

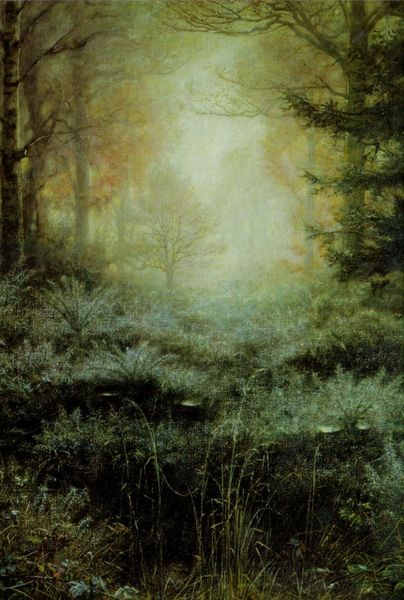

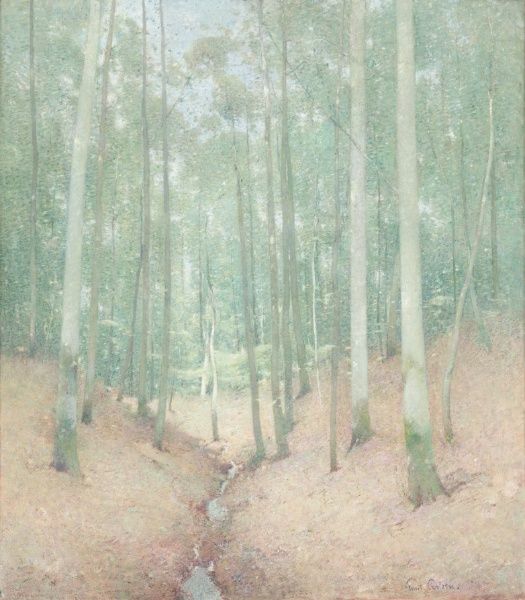

Curator: John Atkinson Grimshaw painted this, Lovers in a Wood, in 1871. The primary medium appears to be oil paint, worked in the plein-air style. What strikes you first about it? Editor: The pervasive gloom, actually. Despite the presence of those two figures, there’s a real melancholic atmosphere here. Almost oppressive. Curator: The figures are very interesting. We see a romantic engagement amidst a societal transformation fueled by the Industrial Revolution. In the setting of late 19th-century Britain, industrial progress significantly changed urban landscapes, and profoundly influenced the roles of men and women in society. Grimshaw frequently placed women centrally in his art, emphasizing their roles and the shifting societal expectations of their time. Editor: Exactly, and notice the materiality of the wood itself. He really captures the textures - the rough bark, the damp earth underfoot. How accessible this locale may have been is also telling in context with the burgeoning factories of the time. Curator: The fog obscuring sections of the scene adds an element of mystery, but it also works as a tool to soften the visual narrative, deflecting stark social criticism and perhaps adding nuance. I also read that his urban paintings offered a critical view of the era's moral climate by highlighting societal disparities. Do you see that here? Editor: Absolutely. This idealized, romantic depiction contrasts sharply with the conditions most people would be facing, further illustrating social inequalities of the time. Think about the labor that would’ve made paints like this so readily available. It begs us to analyze it through production, consumption and use. The figures being almost hidden emphasizes the stark disparities even more by placing luxury over truth, essentially covering over reality. Curator: That's a powerful interpretation. The lovers, nestled within the scene, might indeed be shielded by a crafted and idealized escape. Perhaps the landscape speaks to escapism available to some but unattainable for most, in that era. Editor: Precisely. The material realities underlying the romantic imagery can prompt us to re-evaluate the dominant narratives around beauty and access in 19th-century England. Curator: Yes, I agree. Placing this imagery in broader discourse with identity and politics complicates a simplistic reading of landscape as solely pastoral. Editor: It has given me quite a lot to think about! Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.