photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

coloured pencil

#

orientalism

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

watercolour illustration

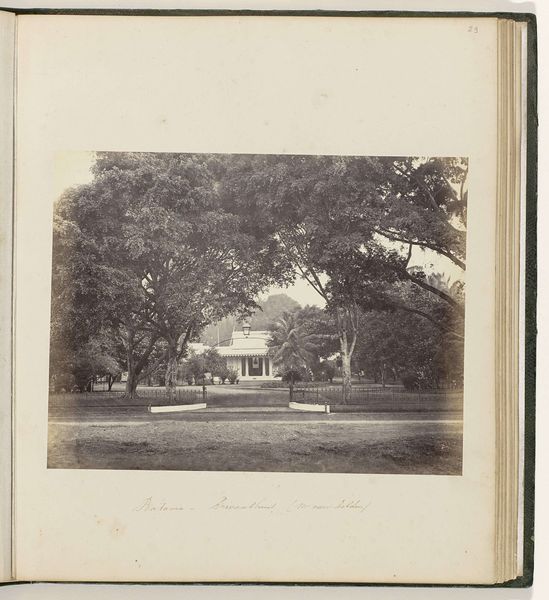

Dimensions: height 217 mm, width 276 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a photograph by A. Kaulfuss, titled "Atjeh, Kota Goenoengan met de Tarman, gevangenis met tempel," created sometime between 1891 and 1894. It appears to be a gelatin silver print. Editor: It's hauntingly beautiful. The monochrome palette lends a gravitas. The way the structure emerges from the tall grass gives it an almost mythic, lost-world feel. There's something very colonial about it, though, something about claiming space through image making. Curator: That's a perceptive reading. This image, like many produced during that period, functions as both documentation and assertion of power. The photograph depicts a prison complex, along with a temple, in what is now Aceh, Indonesia, during a time of Dutch colonial rule. Consider the very act of photographing such a place, the implicit authority it suggests. Editor: Right. The visual language screams control. The photographer’s choice to center the architecture, seemingly dominating the natural landscape, feels deliberate. Who gets to represent whom, and for what purpose, becomes critical here. I also note the implied labor absent from the frame, the people subjugated within those walls whose stories are actively omitted. Curator: Precisely. What might seem like an innocent landscape view is actually a carefully constructed narrative reinforcing colonial hierarchies. The seemingly neutral act of documenting geography becomes entangled with ideological and political agendas. And to be honest I'm unsure who was it addressed to? Who could view this piece at that time? What could they learn from it? It definitely provides some historical facts about its location, however, that seems to be the point in this particular piece. Editor: That is actually a very valuable point to take into consideration as well. It certainly encourages further questioning of whose gaze this image was created for, whose comfort it serves and what specific political or social power does it enhance through it circulation and representation. Thanks for sharing your thoughts on this remarkable historical material, I must say! Curator: Thank you! Exploring these colonial images is not just about looking at the past, but understanding how that past continues to shape our present and perceptions.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.