print, engraving

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 104 mm, width 74 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

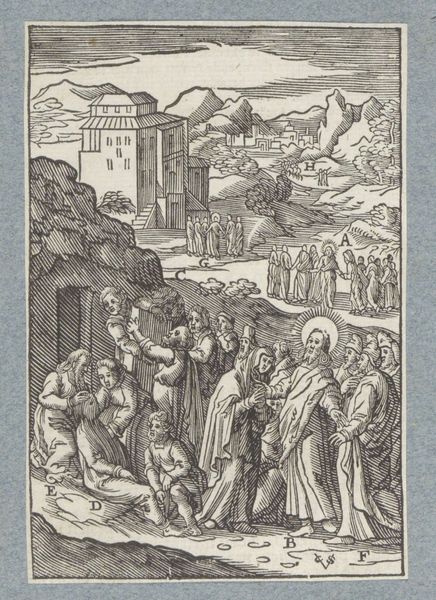

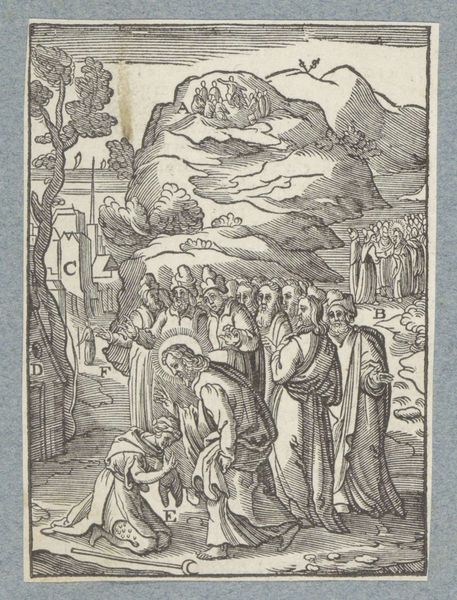

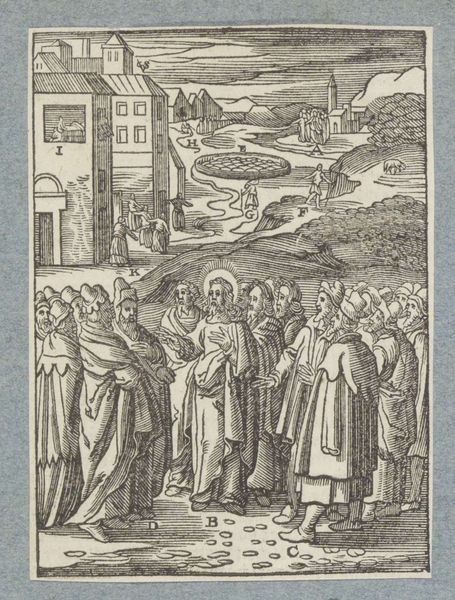

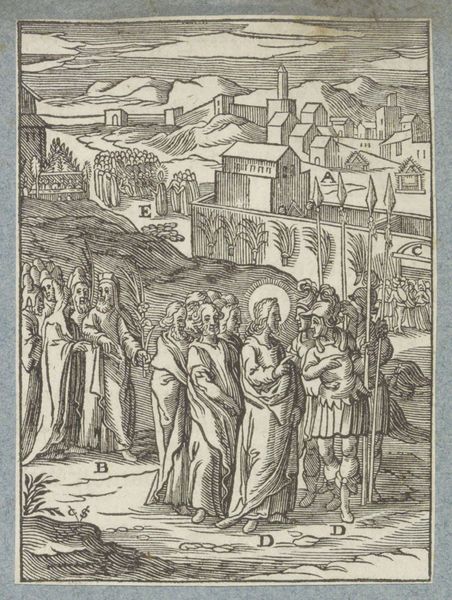

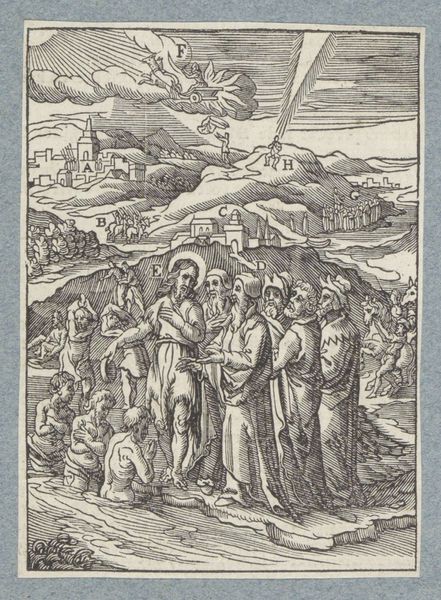

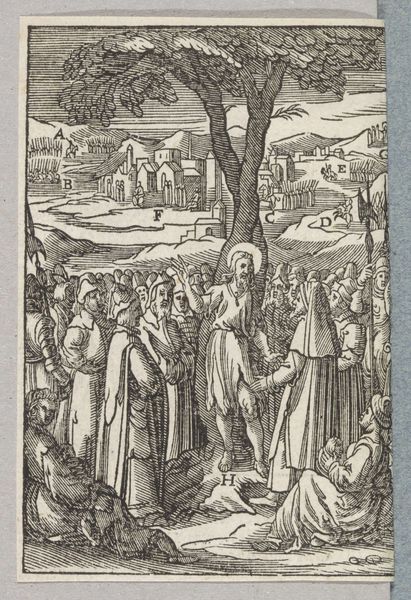

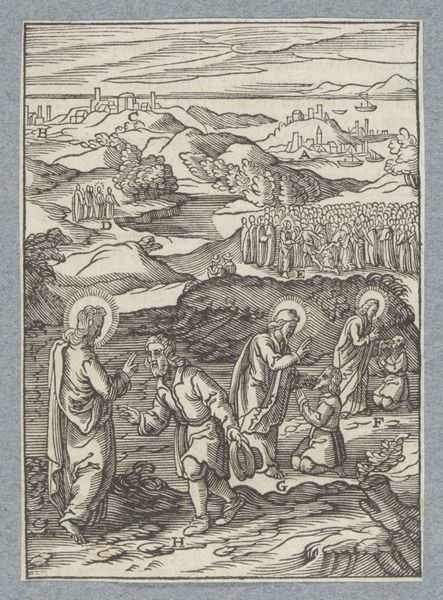

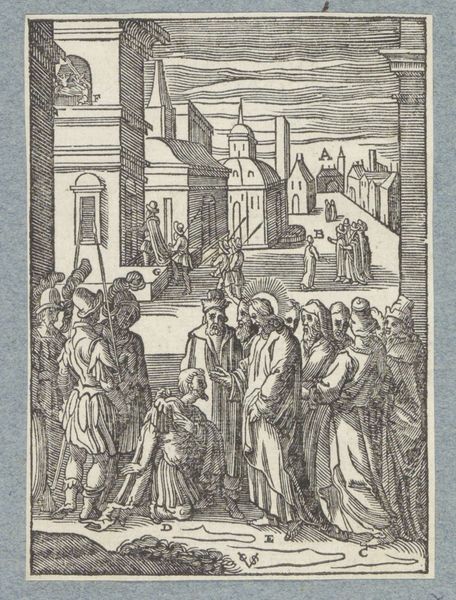

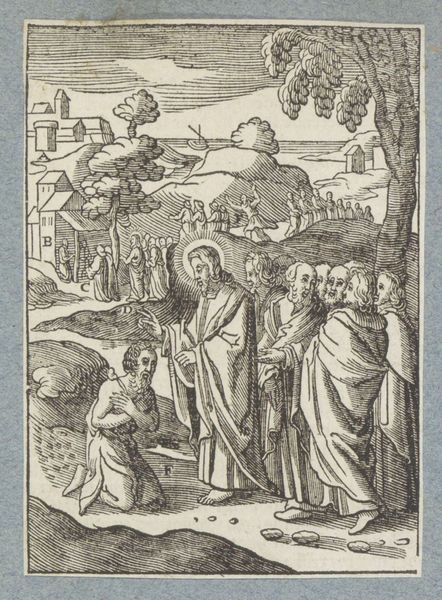

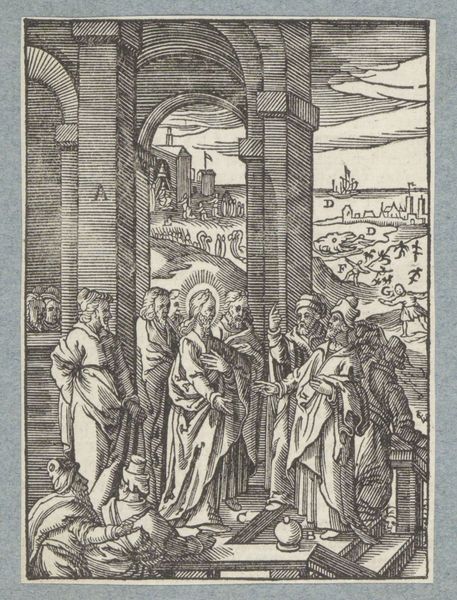

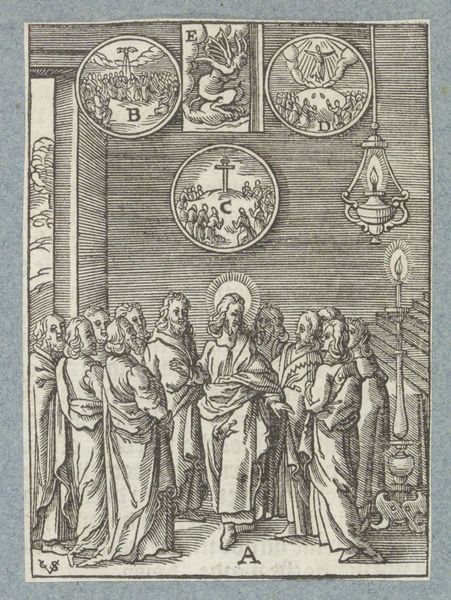

Curator: Let's discuss "Christus geneest een bezeten man," or "Christ Healing a Possessed Man," a print made around 1629 by Christoffel van Sichem II, currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My first impression is the dramatic contrast. The clean lines carve out a chaotic scene, almost like a struggle etched onto the page. Curator: It’s a wood engraving, so that physicality, the cutting into the block, feels quite relevant. We should consider the context: 17th-century Europe was deeply religious, and ideas about possession were often intertwined with social anxieties and power dynamics. Sichem's work serves as a visual tool reinforcing certain religious views. Editor: Exactly, the means of disseminating those views becomes important here. Printmaking made religious narratives accessible. Sichem, working with the material, wood, transformed the word into an accessible, reproducible image. The material almost mimics the wide distribution the Church aimed for. Curator: It speaks to how religious institutions worked to solidify authority by associating themselves with divine power but, viewed critically, also shows their vulnerability through themes like demonic possession. In those days, accusations were used to discredit marginalized individuals and reinforce existing social structures. Editor: The layering is interesting from a purely process-driven perspective. See how the overlapping lines suggest depth and movement. How the image almost appears to ripple outward, the closer we get to Jesus’s aura. And notice that very texture almost obscures, reinforcing the chaotic and disruptive narrative of possession. Curator: True. Moreover, observe the gazes; all are oriented toward Christ and the presumed "possessed" man. It’s worth considering what it does to position the viewer in alignment with these power structures, perhaps inviting an unquestioning embrace of its narratives. Editor: Absolutely, because the sheer accessibility of printed images like these contributed to solidifying beliefs at the material level. Curator: When we view it today, what assumptions might be challenged given our understanding of health, society, and marginalized individuals? Editor: Considering its production method gives us space to recontextualize our viewing today. What did labor and dissemination mean, versus its effect on modern consumers and our belief systems now?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.