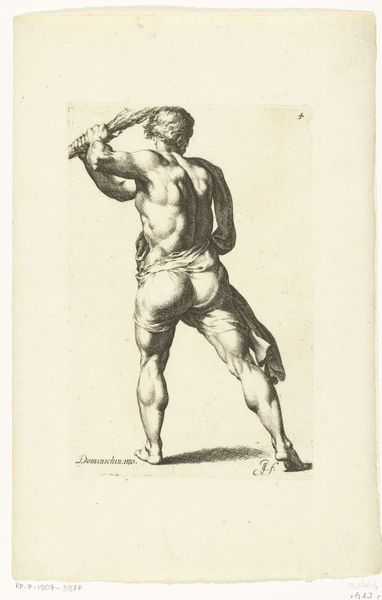

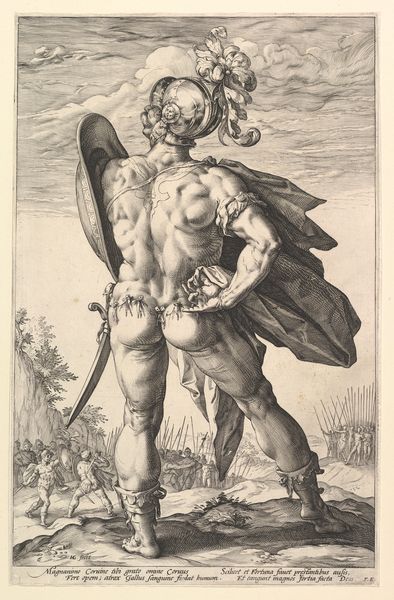

Savage Soldier Swinging a Club 1755 - 1771

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

soldier

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: Image: 4 3/16 × 3 1/8 in. (10.7 × 7.9 cm) Plate: 4 13/16 × 3 7/16 in. (12.2 × 8.8 cm) Sheet: 5 13/16 × 3 3/4 in. (14.8 × 9.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

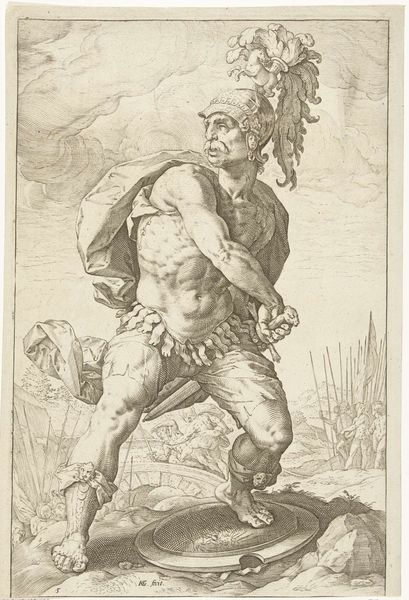

Curator: Philippe Jacques de Loutherbourg's "Savage Soldier Swinging a Club," an engraving made sometime between 1755 and 1771. It's currently held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. What's your immediate reaction? Editor: Stark. Brutal. The high-contrast rendering immediately grabs you, but it's the implied violence in the figure's stance and the club raised high that truly strikes me. It’s less about heroic victory and more about raw, unrestrained power. Curator: That sense of power and brutality is heightened, I think, when we consider the era in which Loutherbourg was working. There's an obvious link here to Enlightenment fascination with the ‘noble savage’ and the political implications embedded within such representations. It's a deeply colonial vision of 'otherness,' using race and civilization to explore what Europe saw as its opposite. Editor: The imagery, however, speaks of something deeper. Look at the specific symbols he uses – the fur clothing, the feather headdress, and the crude club. It is clear the artist is trying to establish an idea of primordial identity. I'm intrigued by the timeless quality—the echoes of ancient barbarism and mythology brought into a contemporary context. Curator: I find myself uncomfortable with the romanticized barbarism and its troubling legacy. It speaks to a desire to essentialize cultures different from the European ideal, to otherize and thus justify domination and erasure through a claim of social and technological progress. This is a narrative that, in effect, casts one civilization as superior, with grave real-world impacts, not just a question of aesthetic tradition. Editor: Perhaps. However, the human need to explain human drives may inevitably include less civilized dimensions of being. Does this art encourage our acknowledgement of base human instincts, irrespective of era? It shows a timeless visual archetype. Curator: It could certainly be read that way, although the visual shorthands chosen here carry a tremendous weight in their historical deployment, a reminder to not lose sight of our social responsibilities as interpreters of such artwork. Editor: Ultimately, the image serves as an important prompt. It shows the potent, and often complicated, dialogue between perceived civility and humanity's enduring drives, be they for triumph or destruction. Curator: Absolutely, It encourages questioning of power dynamics that remain very active today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.