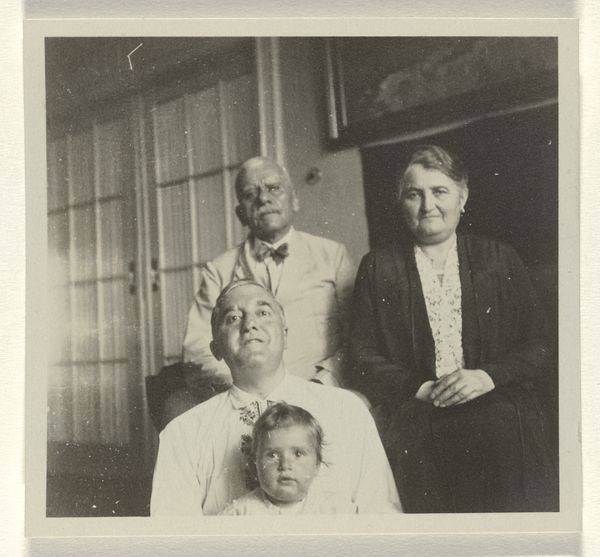

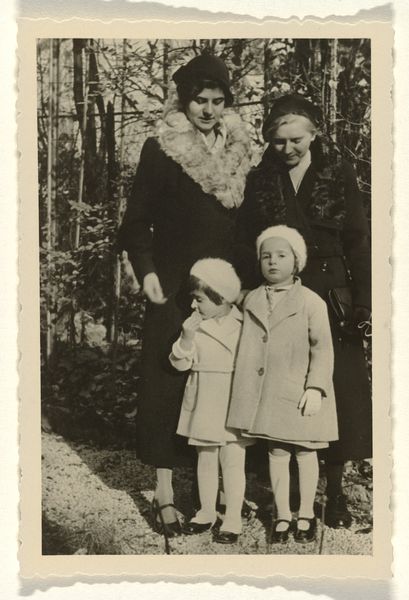

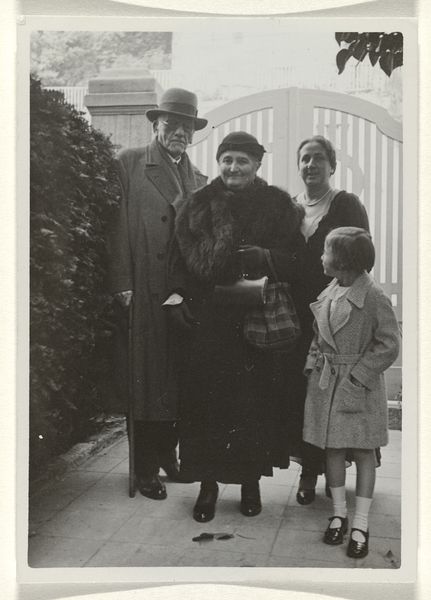

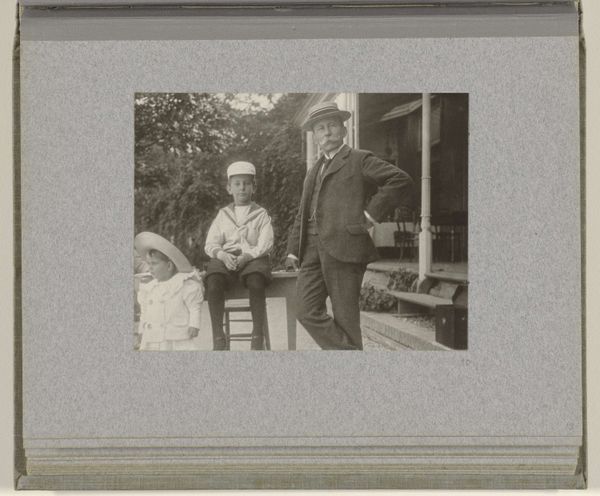

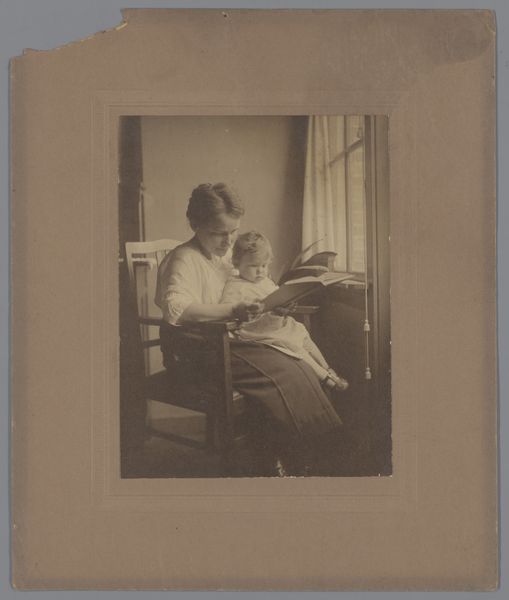

Meir Wachenheimer, Mathilde Wachenheimer-Wertheimer, Eugen Wachenheimer, Isabel Wachenheimer in kamer, 1928-1937 Possibly 1929

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: height 60 mm, width 60 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a gelatin-silver print titled "Meir Wachenheimer, Mathilde Wachenheimer-Wertheimer, Eugen Wachenheimer, Isabel Wachenheimer in kamer," possibly from 1929, by Meir Wachenheimer. It's a portrait of four family members. Editor: It has a quiet, intimate feel. The soft lighting and slightly blurred edges give it the air of a memory, doesn't it? Curator: Indeed. Studio portraiture like this played a key role in shaping familial memory in the early 20th century. Consider how the rise of photography democratized portraiture, previously only accessible to the wealthy. This piece offers insights into bourgeois Jewish family life in Germany before the disruptions of the Nazi era. Editor: It makes you wonder about the sitters—their lives, their hopes, their eventual fate. Looking at them grouped together makes you wonder about each of their specific relationships. Given what was coming in Germany in that period, one also feels a palpable sense of foreboding in their grouping as it hints at later trauma. What social constraints and societal expectations might each person have lived under, based on their positions in the photo and their specific identities? Curator: Good point. Family portraits of this kind are very constructed. Note the subjects are formally posed. The women are seated, the men behind, framing a child at the forefront—emphasizing gender and generational roles. The soft-focus gives the photograph an almost impressionistic painterly effect which served to create artistic feeling but might also have had some element of retouching the photograph. Editor: What strikes me too is how these visual cues intersect with the untold stories lurking beneath the surface. It calls to question which voices or experiences might be overshadowed by the dominant narrative captured in the photograph? Also, who has historically been omitted from these kinds of stories? It demands of us to approach with careful regard. Curator: Precisely. A photograph isn't just a mirror, but rather is both an act of creation and a document shaped by socio-political realities. It prompts us to question whose stories are being told, and perhaps more importantly, whose stories are excluded. Editor: Looking at this now, it becomes not just a family snapshot but a meditation on history, memory, and representation itself. Curator: Exactly. Considering the photographer and their subject, this work carries layers of cultural and social relevance far beyond its simple visual representation. It truly acts as a testament to their era.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.