print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

landscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 174 mm, width 209 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

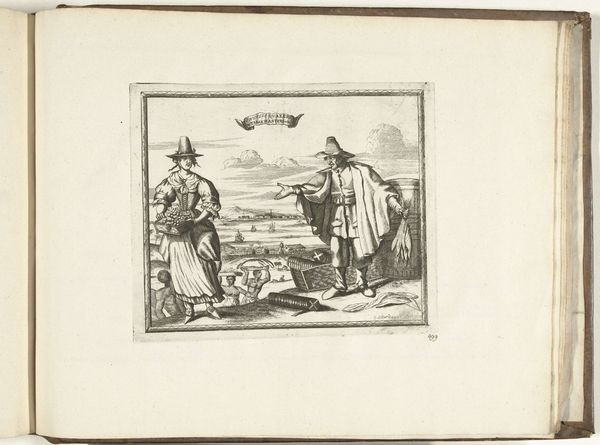

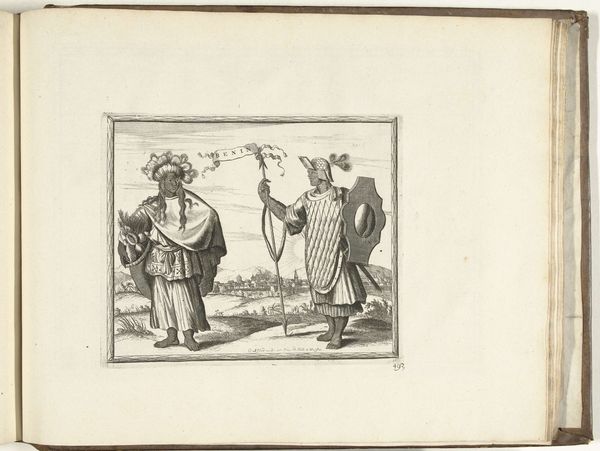

Curator: Looking at this piece, “Inwoners van Luanda, 1726” by Carel Allard, currently held at the Rijksmuseum, my first impression is one of rather stilted grandeur. It's almost theatrical, isn't it? Editor: Indeed, there's a clear compositional balance with the two figures framing the scene. What really stands out is the stark contrast achievable via engraving, Allard's chosen medium. Curator: Yes, an engraving provides this piece with clean lines and allows the artist to produce multiple copies cheaply and fast. I think it’s worth remembering that these weren’t independent artworks meant for art galleries, but rather prints usually found inside of travelogues that allowed Western audiences a chance to encounter different territories through its people and the surrounding landscapes. Editor: Absolutely, the formal portrayal of the two figures—their dress, stance— it all reads as a very deliberate performance of power and status for consumption back home. I am particularly intrigued by their hats and robes: I'd be interested to know more about where these items came from, where they produced in Luanda, if these attires belonged to dignitaries or noblemen, and which workshops helped create them. Curator: Good question! They do indeed strike me as powerful visual signifiers—especially that somewhat fantastical cityscape backdrop with European ships entering its port. The material reality is that this imagery served a colonial gaze, didn’t it? It reinforces a sense of Europe's power, presenting it as both 'discoverer' and implicitly, ruler of such faraway places. The focus of course becomes less about Luanda's inhabitants themselves, and more on the wealth its port enables. Editor: You are probably right! Yet consider the precision Allard employed when rendering different tones and textures just with a burin! It suggests that although he might never had actually visited Luanda, he took seriously translating Luanda to others according to his European Baroque visual knowledge. In the print’s design, note how the ships align carefully alongside figures; each element has an intricate geometric structure meant to express authority. Curator: Ultimately, through the medium and circulation, this print, like so many others of its kind, functions as a sort of colonial propaganda, justifying trade exploitation with one precise line and tiny cross-hatching after the other. Editor: Perhaps. But paying attention to these details has allowed us to engage, even if critically, with what such image really represents about the interaction between those who created it and those who viewed it in very distinct and complex historical contexts.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.