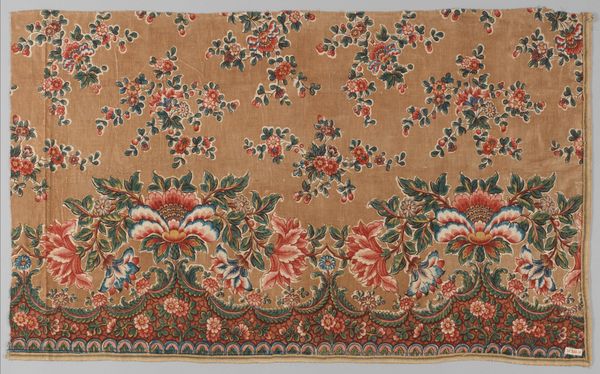

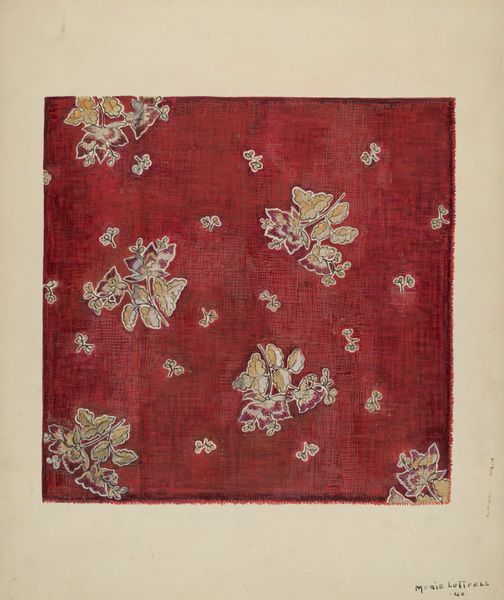

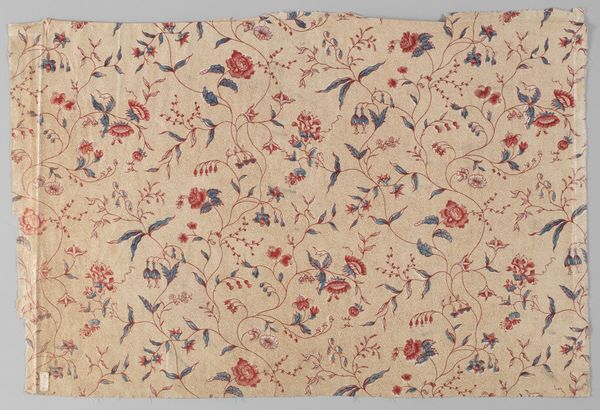

textile, cotton

#

organic

#

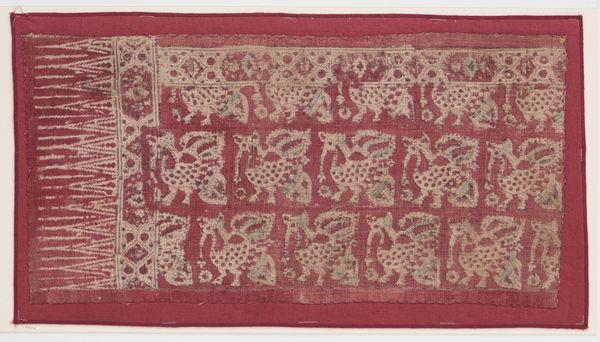

textile

#

geometric pattern

#

organic pattern

#

geometric

#

cotton

Dimensions: 81 1/2 x 43 1/2 in. (207.01 x 110.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

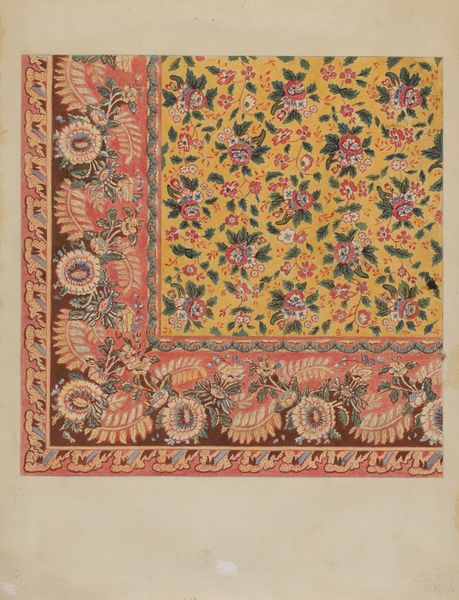

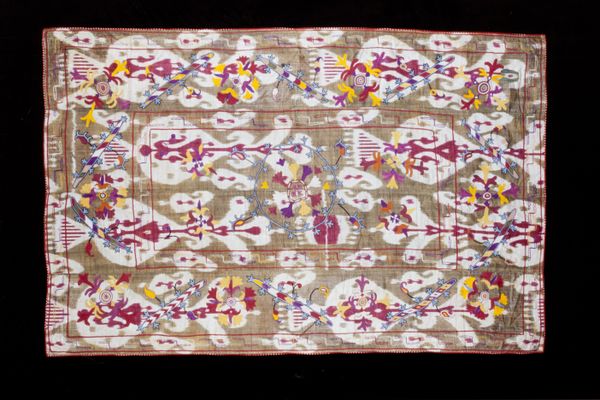

Editor: This is a striking skirt cloth, or *kain sarong*, probably from the late 19th or early 20th century. It's made of cotton and is currently at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. The contrast between the red and dark blue sections really catches the eye, and the botanical motifs are quite charming. How would you interpret its role within its historical context? Curator: Textiles like this were deeply embedded in the social fabric. Think about the painstaking labor involved in producing these intricate patterns, often by women in their homes. These textiles weren't just clothing; they were visible markers of status, community affiliation, and cultural identity. The motifs might reflect local flora or carry symbolic meanings related to fertility, protection, or social hierarchy. The market for these textiles, and their display within homes and in public life, would have spoken volumes about power dynamics and economic exchange in that era. Do you notice any details that suggest a specific geographic origin? Editor: Well, I am seeing strong evidence of organic patterns but it would be difficult to pinpoint without a better understanding of specific botanical motifs used in different regions. But does the existence of mass-produced textiles influence how an audience interprets traditional handcrafted textiles like this one today? Curator: Absolutely. The arrival of cheaper, industrially produced textiles would have presented both a threat and an opportunity. Traditional textile production might have become a symbol of resistance to colonial influence, or adapted by integrating new materials and techniques, leading to unique hybrid forms. Think about how museums today acquire and exhibit such textiles – it's a powerful act of preservation and cultural valorization. We are creating meaning but are we perpetuating a story that silences some groups. Editor: I hadn't thought about how the rise of industrialization might have influenced the perceived value of something like this! Thanks for making me consider the socio-political complexities embedded in everyday objects. Curator: And thank you for noticing the subtleties! These textiles remind us that even the simplest objects can be rich sources of historical and cultural information.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

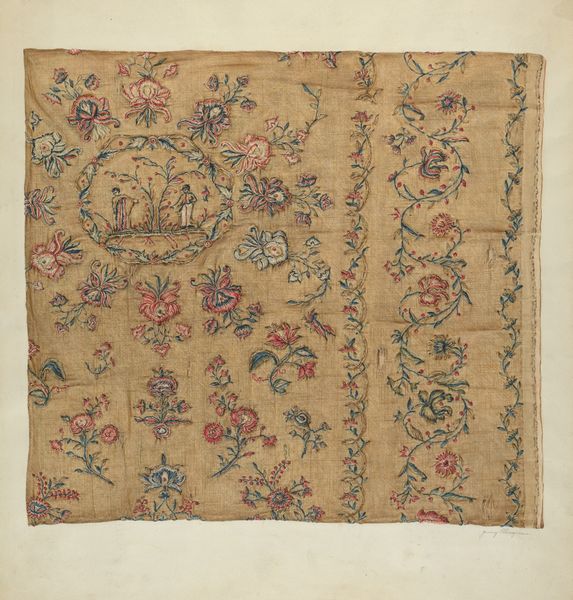

The Indonesian island of Java is renowned for its production of batik textiles. Using a resist-dyeing process, batik makers, usually women, draw intricate patterns in wax (the resist) with a pen-like device over cotton cloth. Then they soak the fabric in successive batches of color dyes. Because the wax resists dyeing, once it is removed, the original design remains. The work is also known as tulis, or writing. Antecedents of batiks can be traced back to Indian textiles from the first millennium CE. Evolving on Java from 1600s court culture into a major industry under 1800s Dutch colonial rule, batiks feature a range of motifs, many of which are uniquely Javanese. Collected in the early 20th century by Lily Place, a Minnesota native based in London, Paris, and Cairo, these two textiles demonstrate the appeal of later Javanese batiks to foreign tastes. Decorated with scrolling, flowing vines, the traditional skirt (sarong) cloth shows a mixture of Chinese, Javanese, and European influences; for example, the roses and fluttering butterflies come from Dutch horticultural books. The other panel features stick-like figures associated with Javanese puppet performances, or wayang kulit, of Hindu epics still performed for a Muslim-majority nation. However, its square format conforms to a man's headcloth, which would typically not include such imagery. These adaptations reveal how popular traditional Javanese imagery, such as the wayang and the central “tree of life” motif, were among the clientele of batik artisans.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.