#

photo of handprinted image

#

aged paper

#

light pencil work

#

photo restoration

#

ink paper printed

#

parchment

#

light coloured

#

old engraving style

#

white palette

#

golden font

Dimensions: height 94 mm, width 76 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

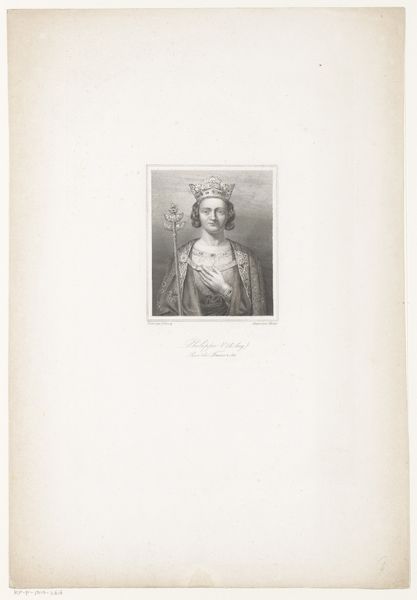

Editor: We’re looking at a portrait of Dagobert III, King of the Franks, by Ferdinand Delannoy, created sometime between 1838 and 1841. It’s interesting how the print medium gives this royal portrait a certain accessibility, almost like a widely distributed image. What kind of social impact do you think a piece like this might have had? Curator: That's a crucial observation. Consider the socio-political climate of the 19th century. The proliferation of printed portraits served a distinct purpose: constructing and disseminating specific images of power. While seemingly 'accessible,' who really had access, and what message was being sent about kingship in a post-revolutionary world? Editor: So, it’s not just about accessibility, but also about control of the narrative? Were these prints aimed at legitimizing or perhaps even modernizing the idea of monarchy? Curator: Exactly. It's less about democratizing access to art, and more about reinforcing power structures in a changing social order. Notice the details: the crown, the scepter. How do these symbols, when reproduced and circulated, impact the public's perception of royal authority? Were they effective? Editor: That’s a perspective I hadn’t considered before. I guess I saw a printed portrait and immediately thought of wider reach. I didn't really think about the specific goals behind its distribution, and what values it would reinforce, especially thinking about this portrait as propaganda of sorts! Curator: It's a subtle but important distinction. These images functioned as a form of public address, negotiating the shifting relationship between ruler and ruled in a world increasingly aware of its own agency. Think about the political messaging, especially with royalty struggling to find new meaning in the nineteenth century. What I find exciting is the realization that at the heart of an image of power, you might be seeing fragility. Editor: That adds so much complexity! Thanks, this makes me think very differently about how images of authority are presented, and consumed.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.