Copyright: Public domain

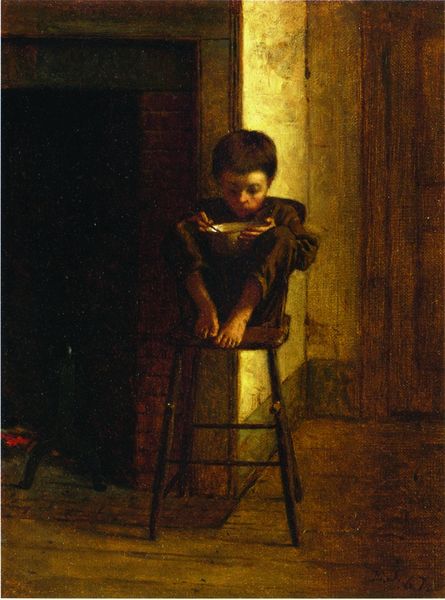

Editor: So here we have Augustus Edwin Mulready’s “A London Jo - the End of the Day,” an oil painting from 1884. The figure of the boy, combined with the bare feet and tattered clothing, really emphasizes his vulnerability. What jumps out to you in this piece? Curator: What strikes me is the depiction of labour. This isn't just a sentimental portrait, but an exploration of the materials of poverty. Look at the broom, worn and functional, a tool of the boy’s trade. It speaks volumes about the socio-economic conditions and the materiality of work in Victorian London. Editor: I hadn't thought about the broom as a key material. It seems like such a small detail. Does it tell us something about who was viewing or commissioning the artwork at the time? Curator: Exactly. Mulready highlights not just the boy's plight, but the means by which he survives, placing him firmly within a specific, working-class context. The oil paint itself is used almost as a document, recording the textures of poverty and the hard reality of labor. How does the setting – the implied location - interact with this reading? Editor: Good point! The cold stone of the steps underscores the unforgiving nature of his environment. So, the materials and the process of his labor define his existence as represented here. Curator: Indeed. Mulready's work offers us insight into the physical and social realities faced by working-class children in Victorian England, a stark contrast to the more romanticised depictions of childhood prevalent at the time. It really begs the question: What kind of transaction is occurring between the subject, the painter, and the viewer? Editor: This has definitely changed my view, framing it more about labour conditions rather than a general, sentimental observation. It all boils down to how he made his living. Curator: Precisely. Considering art through its material production opens up valuable perspectives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.