collage, painting, oil-paint

#

cubism

#

collage

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

geometric

#

modernism

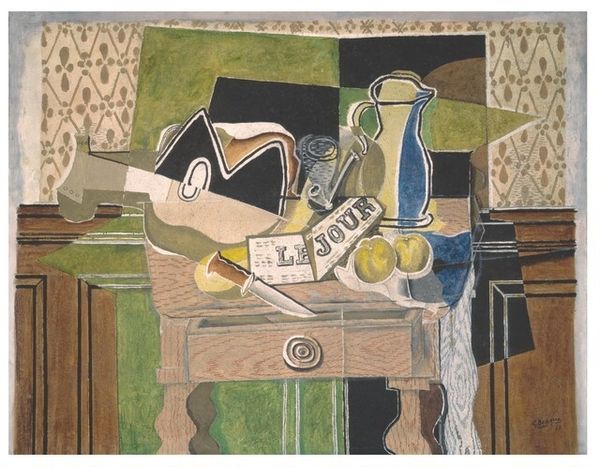

Dimensions: overall: 81.3 x 130.8 cm (32 x 51 1/2 in.) framed: 116.8 x 167 x 12 cm (46 x 65 3/4 x 4 3/4 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Let's turn our attention to "Still Life: The Table," an oil and collage artwork created by Georges Braque in 1928. What are your initial impressions? Editor: It’s visually arresting. The flattened perspective, the subdued palette, the geometric forms all create this kind of dreamlike space—familiar, yet fragmented. There’s a tension there that I find immediately captivating. Curator: The materiality is indeed crucial. Braque’s choice of oil paint, combined with collage elements, speaks to the Modernist disruption of traditional art hierarchies. He’s not just depicting objects, but actively constructing them through varied media. It prompts the question: what defines "art" when everyday materials are integrated into the painting's surface? Editor: And who is this "art" for? Considering the rise of consumer culture at this time, it feels almost like a commentary on commodity fetishism, right? We have these objects, divorced from their production, simply existing on a tabletop for aesthetic consumption. The fractured forms also mirror the fragmented realities experienced by many in a rapidly industrializing world. Curator: Exactly. And if we think about Braque’s process—the way he builds up the composition, layer upon layer, adjusting shapes and colors until he arrives at the final form—we start to understand how labor is inscribed within the artwork itself. It is in no way a passive record. It requires active labor, that we too often ignore when considering this movement. Editor: I think we must consider it too within the long trajectory of still-life painting. Traditionally, it was a demonstration of skill, a display of possessions. Here, though, Braque isn't simply reproducing a scene. He's deconstructing it, analyzing it, almost dissecting it. It breaks from the representational aspect of painting entirely. Curator: Which returns us to the fundamental question: what is he trying to convey by upending tradition like this? Is it purely aesthetic, or does it function as a sort of social critique through the flattening of objects? Editor: I think it’s both. Braque is pushing the boundaries of visual representation while implicitly reflecting the social anxieties of his era. I wonder too how race plays a role in all of this. As Cubism borrowed liberally from African masks, could this painting be an act of cultural appropriation that reinforces asymmetrical power dynamics? Curator: The use of collage makes it a provocative work, which allows us to think deeply about modernism's broader engagement with the world around it. Editor: Precisely. It makes me eager to understand its resonance across time, how its radical formal disruptions can spark contemporary debates on power, representation, and the very purpose of art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.