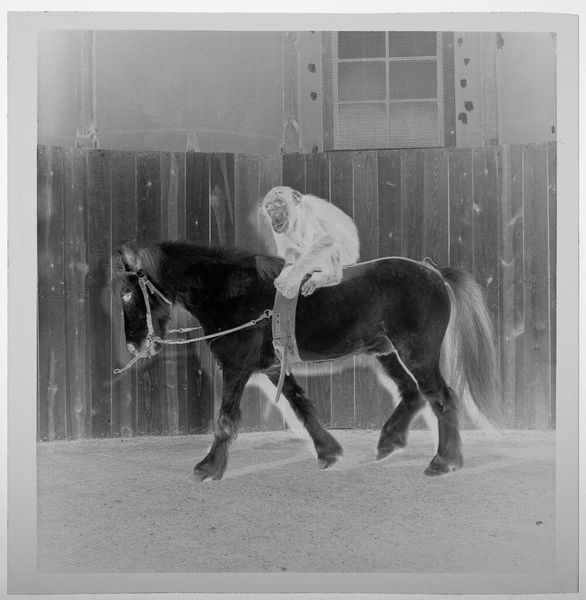

photography, sculpture

#

animal

#

sculpture

#

figuration

#

photography

#

sculpture

#

black and white

#

horse

#

monochrome

#

realism

#

monochrome

Copyright: Public domain

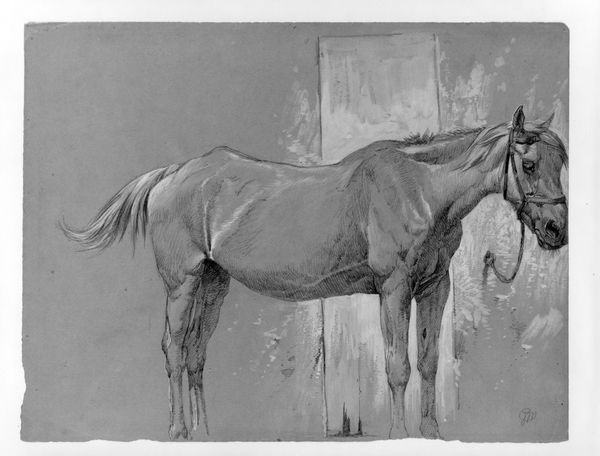

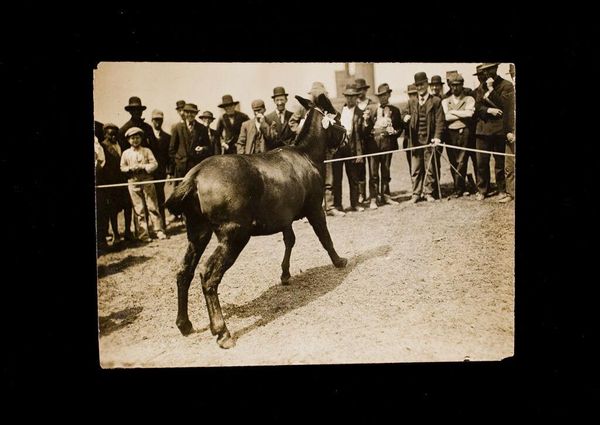

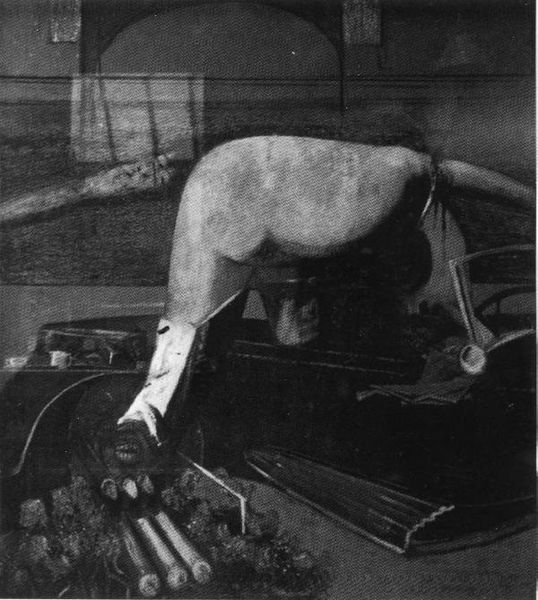

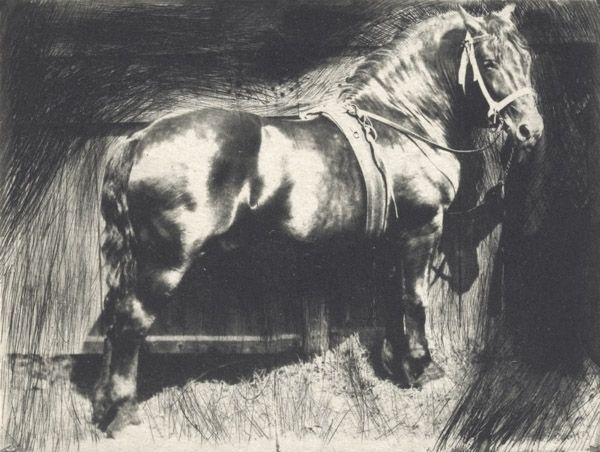

Curator: Here we have "Clinker, G509," a work made in 1892 by Thomas Eakins, recognized for his explorations of realism through both photography and sculpture. Editor: Immediately, the photograph strikes me as deeply melancholic. It feels almost spectral, like a ghost captured in monochrome. The texture seems so... still. Curator: Absolutely. This work can be viewed within the context of Eakins's broader interest in capturing anatomical accuracy and movement, specifically concerning equine locomotion. He challenged conventional representations of horses, engaging in rigorous studies using photography, which he then applied to his sculptures and paintings. His work with horses occurred alongside broader Victorian anxieties around the body, industrialization, and control. Editor: That Victorian obsession with control… It makes me think about the very pose of the horse. Captured almost clinically, with the stark backdrop, it's like he's trying to dissect the essence of the animal but perhaps losing its spirit in the process. Doesn't the backdrop resemble a dissecting room? Curator: Some scholars interpret Eakins’ use of photography here as a way of democratizing knowledge. Before accessible photographic technology, representations of the natural world—of anatomy or motion—were governed by those who held specific class and educational privileges. So the monochrome flattens those hierarchies in a way. Editor: Perhaps, but there's also something inherently cold about it, isn’t there? Even if democratized, isn't something lost when beauty is quantified like this? What if he captured the horse's personality rather than just the mechanics of its movement? Curator: That tension—between objectivity and subjective expression—really lies at the heart of realist artistic and scientific pursuits during the period. This is a critical point when we start examining broader historical currents within intersectional feminist and sociological lenses. It compels us to rethink gendered hierarchies that shaped access to the artistic establishment, photographic tools, and knowledge production. Editor: Yes! It all comes back to who gets to hold the camera and who becomes the subject of its gaze. Even in capturing movement, is something stilled? I still can't shake this deep feeling of pensiveness. Curator: That emotional response is what Eakins himself strived for in much of his later work. Perhaps you are responding not only to a time but also to an artistic practice deeply fraught with its own contradictions. Editor: Precisely! And those lingering questions, perhaps, are what keep it eternally alive.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.