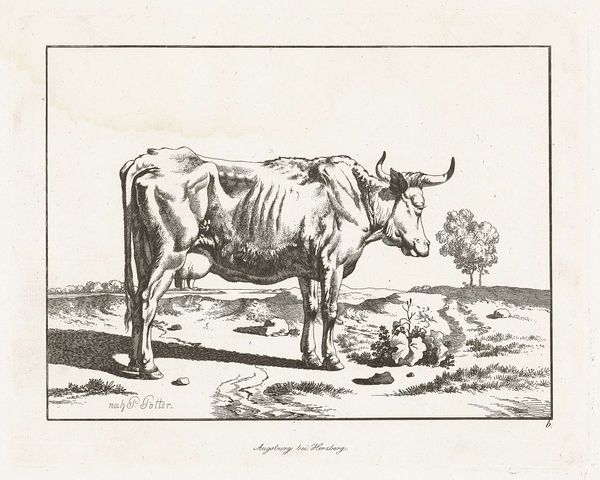

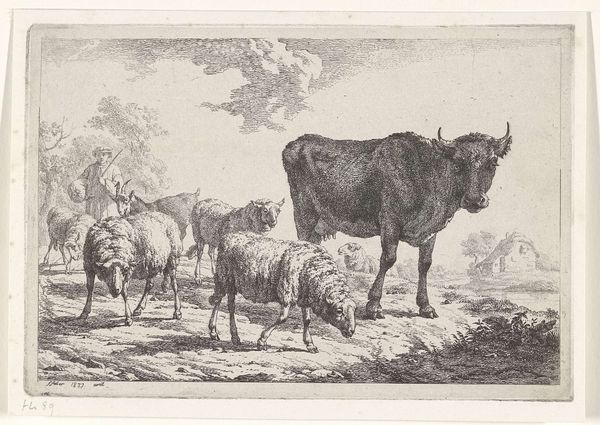

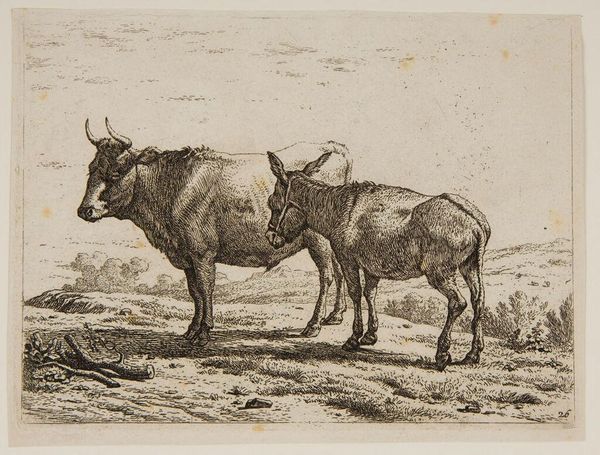

print, etching

#

animal

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: height 201 mm, width 149 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: I'm struck by the simplicity of this etching, it seems so understated. Editor: Agreed. It's quite gentle, a very pastoral mood, wouldn't you say? Let me introduce our listeners: what we’re seeing here is an etching titled "Koe en schaap," or "Cow and Sheep," created in 1828 by Frédéric Théodore Faber. The medium is simple: print and etching, which impacts the materiality. What is interesting, though, is how closely this print participates in 19th century discourses around rurality and idealized pastoral labor. Curator: The contrast really emphasizes the textures, doesn't it? Look at the rough hide of the cow compared to the fluffy fleece of the sheep, and how Faber achieves that with just lines. There's a real labor in that. I can feel the amount of work required to bring the animals to life with such accuracy. The cross-hatching adds incredible depth, giving shape to the bodies through meticulous mark-making. Editor: Absolutely. This level of detail situates Faber's etching squarely within broader societal concerns: industrialization and the yearning for an idealized rural past. What stories do these images tell? Are we meant to admire these animals in their natural state, perhaps even long for a pre-industrial existence? What does it say about land ownership and the role of agriculture in society? It becomes much more political than just "cow and sheep." Curator: Precisely, but on the level of labor we are witnessing how an increased societal desire for naturalism in genre paintings trickled down through consumer culture. Prints like these were a method of disseminating cultural ideas of bucolic living with those who could not necessarily afford an oil on canvas. Editor: Thinking about it more, there's something unsettling in the romanticized simplicity. Were these images genuinely celebrating the realities of rural life, or were they masking the struggles and inequalities inherent in agricultural labor? Consider the impact on children, their labor devalued because seen as natural? It is difficult to divorce these artistic depictions from questions of land use and power dynamics, or indeed from broader questions about capitalism and rurality, both then and now. Curator: Indeed, those socio-economic pressures become increasingly evident through this focus. Viewing art history as labor brings forward new connections in the past to questions of material culture in the present. Editor: Seeing the art, not as some romantic, sentimental object, but instead for what it represents, it's about creating discussions on the historical moment, a real way to challenge dominant narratives about nation, class, gender, and race.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.