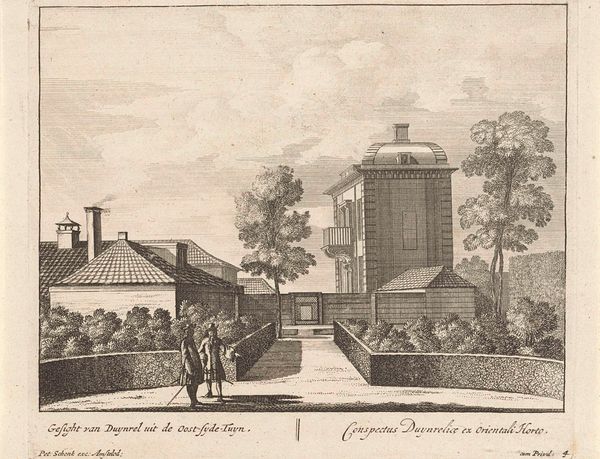

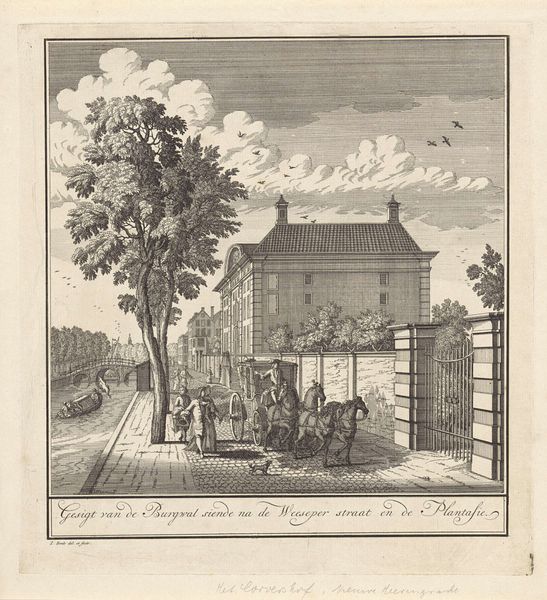

print, engraving

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

landscape

#

cityscape

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 307 mm, width 426 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this print, it's intriguing to consider how F.J. Walther rendered "Gezicht op Paleis Het Loo, gezien vanuit het zuiden" in 1760. This engraving presents the palace as seen from the south. Editor: It certainly gives off an aura of established wealth, doesn’t it? You can almost smell the powdered wigs. But beyond that, the sheer technical skill in the etching is impressive – just look at the textures they've created to simulate brickwork and foliage! It strikes me how industrial image reproduction technologies were even deployed to convey status in that moment. Curator: Absolutely. Consider the engraving itself—the process, the labor involved in creating and distributing these images. It made the palace, and by extension, the Prince of Orange, accessible to a wider public through consumption. The reproducible nature transforms it from a singular artwork into something with a broader reach, a token of the elite for popular consumption. Editor: It’s also fascinating how Walther chooses to frame the palace. He's very deliberately presenting this specific image of power and the imagery around the palace. By presenting the image from a certain direction, with fashionable individuals promenading at the front, that social dynamic becomes intertwined with the palace's narrative, turning the building into not just a landmark but an active social setting. Curator: Precisely! These figures populate the scene as if staging a play. And that staged feel wasn’t by accident: the artist's choice of baroque landscape aesthetic made the statement all the stronger. It emphasizes artifice in art, where the depiction of an open field, and how a materialist would use something reproducible, highlights the culture and economic forces that upheld these power dynamics. The deliberate act of choosing engraving speaks volumes. Editor: In short, this print is more than just a depiction of a pretty building; it is a tool used to uphold specific cultural values of its time. Curator: Exactly. It urges us to question how art participates in socio-political dynamics by embedding these concepts within easily reproducible material formats. Editor: That’s given me plenty to think about. Curator: Agreed; it seems this piece offered a surprising amount of information on the construction, use, and distribution of cultural statements during this period.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.