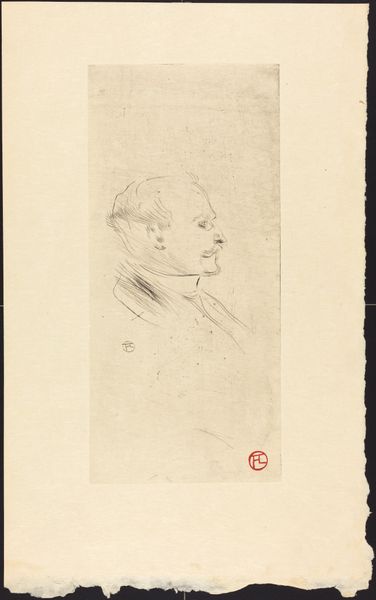

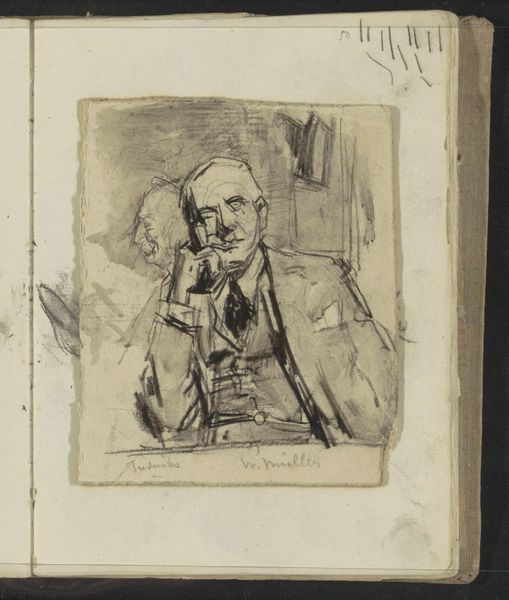

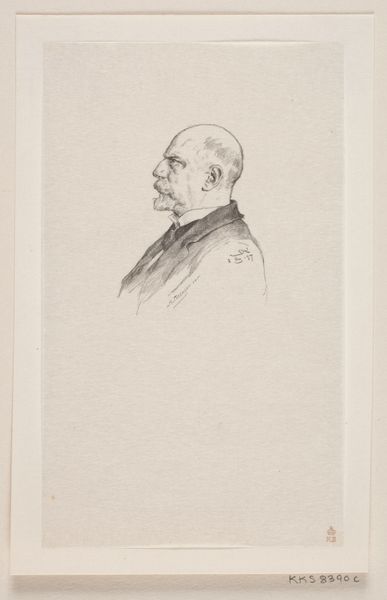

drawing, paper, ink

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

paper

#

ink

#

realism

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

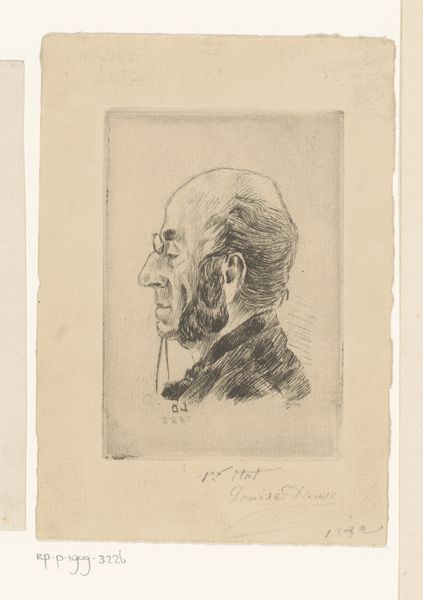

Curator: Straightaway, it feels melancholic. See how the dark ink bleeds a little around the edges? It gives him a soft, almost sorrowful aura. Editor: That's interesting. This ink drawing on paper, entitled "Portret van een man," dates roughly from 1843 to 1864 and is by Coenraad Hamburger. The sitter's expression, along with the portrait’s inherent realism, potentially says a lot about 19th century bourgeois Dutch society. Curator: Bourgeois, sure, but something deeper, too. His eyes seem heavy, like he carries the weight of the world. It’s interesting how little detail there is. Just the barest hint of a coat, almost no background. It's as though Hamburger is showing us a glimpse into the sitter’s very essence, without distraction. Editor: Or perhaps critiquing that essence? There's a subtle tension, don't you think? The formal nature of a portrait, historically reserved for those of stature, is juxtaposed here with an intimate rawness in style, particularly evident in his weathered face. Curator: I suppose that raises a question of power: who gets to be portrayed and how? What aspects of his being are rendered visible, and what are omitted? But maybe the imperfection is what grants its emotional honesty! The lines aren't precise. Instead of erasing and trying to create the perfect shape, Hamburger seems to embrace the flawed form. Editor: Precisely. And how does that "flawed form" relate to notions of masculine identity? The subject has a clear beard, but he looks tired. This could perhaps subvert normative ideals that associate masculinity with strength and youthfulness. The sitter looks, quite frankly, world-weary, burdened by his status, and his historical positioning as a White male in a period of tremendous change and progress. Curator: Progress perhaps, but I do get an idea of reflection in the piece, as if he’s staring back into the past as well. Either way, I'll certainly remember him. Editor: It’s a piece that challenges us to look beyond surface representations, and invites considerations of intersectional relations involving class, gender, and era. It certainly bears repeated contemplation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.