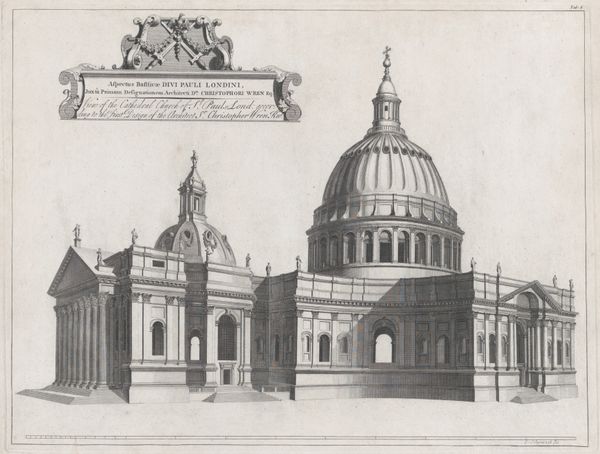

The South East Prospect of the Cathedral Church of St. Paul, London (Overton's Prospects) 1720 - 1730

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving, architecture

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

cityscape

#

engraving

#

architecture

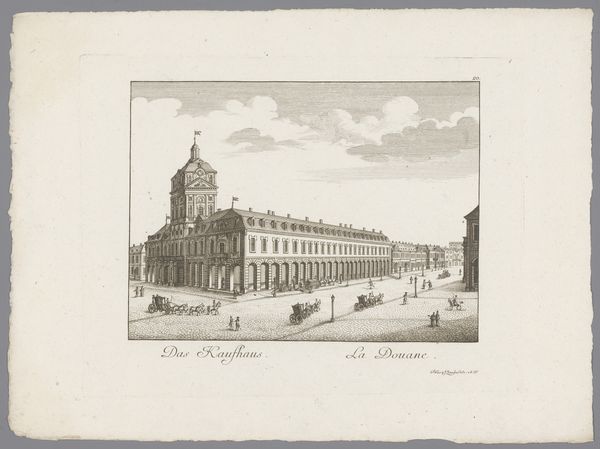

Dimensions: sheet: 6 1/4 x 9 in. (15.8 x 22.8 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Let's consider this detailed engraving from between 1720 and 1730, "The South East Prospect of the Cathedral Church of St. Paul, London," created by Benjamin Cole, now held in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. What's your initial take? Editor: Monumental. I'm struck by the almost obsessive rendering of architectural detail. Look at how every brick, every column, is painstakingly articulated. You can almost feel the weight of the stone. Curator: The engraving offers a fascinating insight into the social hierarchy reflected in architecture. St. Paul's, rebuilt after the Great Fire, wasn't just a religious space; it was a symbol of London's resilience and, by extension, Britain's imperial ambitions. The towering structure dominating the skyline served as a constant reminder of the power held by the church and state, wouldn’t you agree? Editor: Absolutely. And think about the labour involved in creating both the cathedral itself and this print. The extraction of materials, the skilled craftsmanship of the stonemasons, and then Cole's meticulous engraving – all these represent an immense investment of human energy and resources into projecting a particular image of authority and control. The lines speak volumes, a rigid testament of labor. Curator: Yes, and it goes further. Who were the people who could afford to own such a print? Who were encouraged to view it? The representation of ordinary citizens here almost disappears in service to the magnificent facade of St Paul's; this speaks volumes. Editor: Good point. Also, the mass production of engravings like this one allowed for wider dissemination of that architectural imagery, literally etching the cultural importance of the building into the popular consciousness. It's a form of propaganda, really, albeit a beautiful one. Think about how many impressions could be made... Curator: Precisely! It is an advertisement. It helped cultivate a sense of national pride, intertwined with religious faith, that was fundamentally linked to colonialism and class structures. The image served not just to represent the world as it was, but to mold the world as those in power wanted it to be. Editor: It makes you think about the modern production chain too. To be honest, the skill and attention involved stands in sharp contrast to today's means of disseminating images. Curator: This has made me really appreciate how much an image can conceal beneath its initial, apparent celebration of grandeur. It’s necessary to investigate what that grandeur may eclipse in its own creation and legacy. Editor: Indeed. It's easy to get lost in the beauty of the engraving, but it is more important to appreciate the material and historical processes through which that beauty came into being and what power it ultimately served to uphold.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.