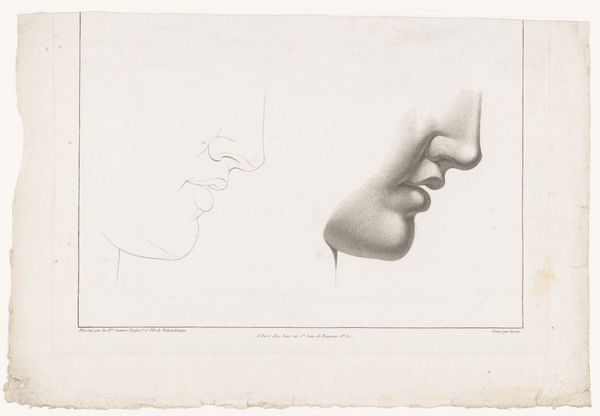

drawing, pencil, graphite

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

self-portrait

#

figuration

#

personal sketchbook

#

idea generation sketch

#

pencil

#

line

#

graphite

#

sketchbook drawing

#

academic-art

#

realism

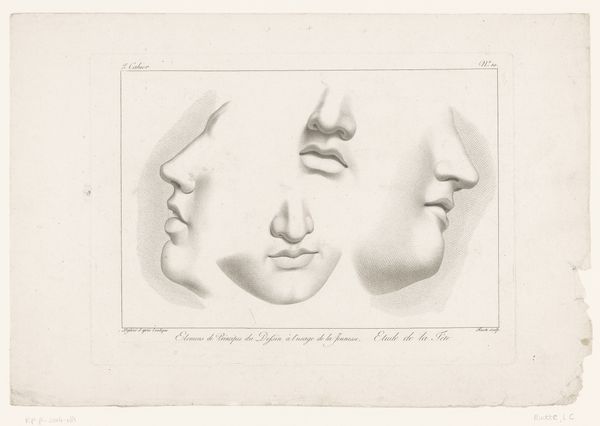

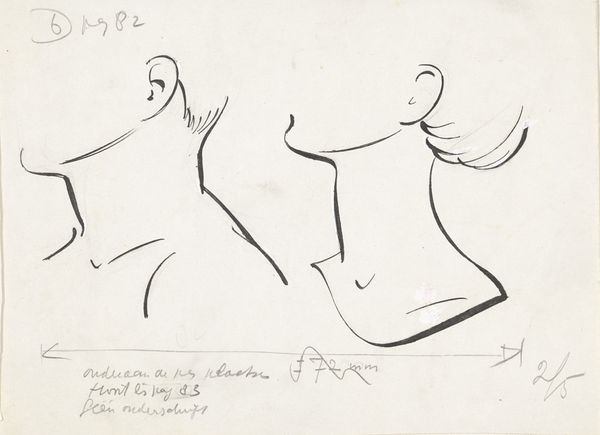

Dimensions: height 240 mm, width 342 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

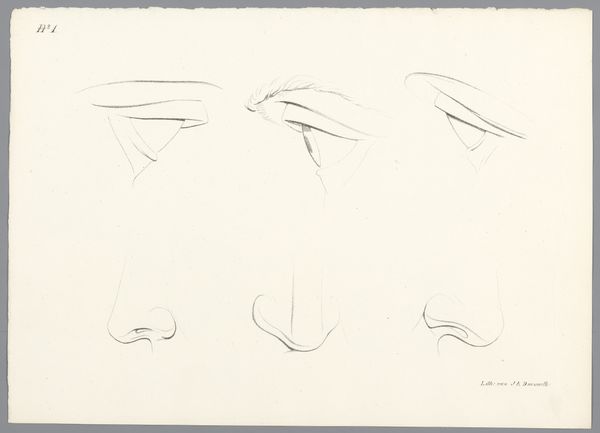

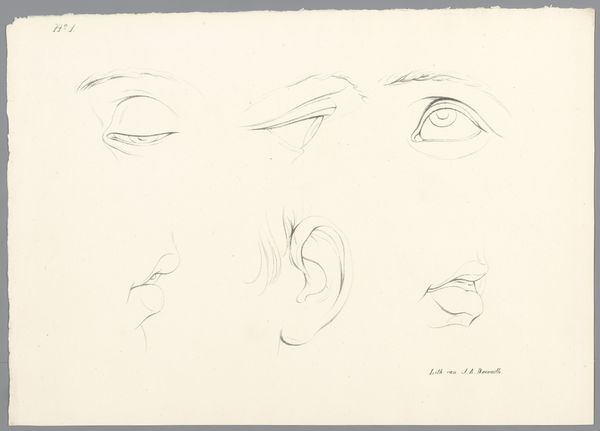

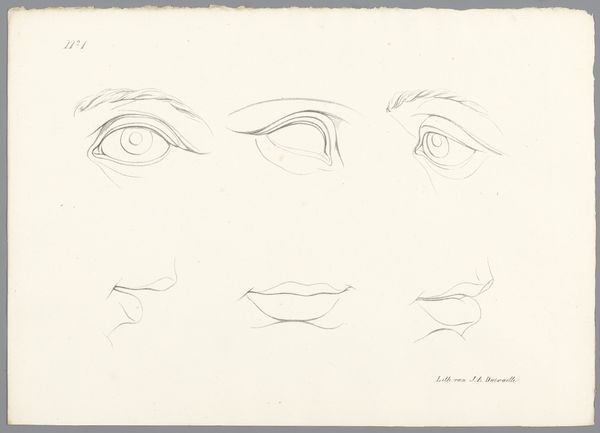

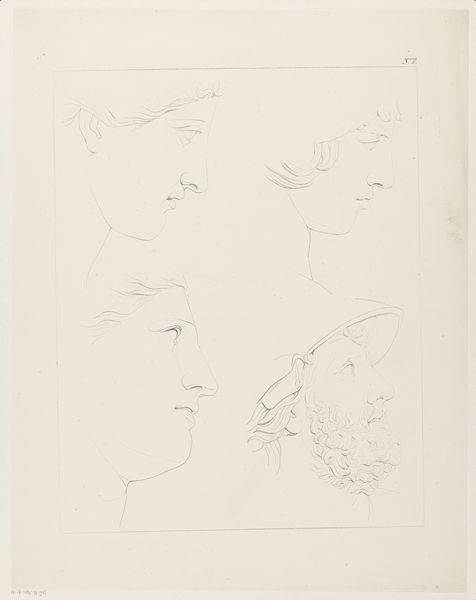

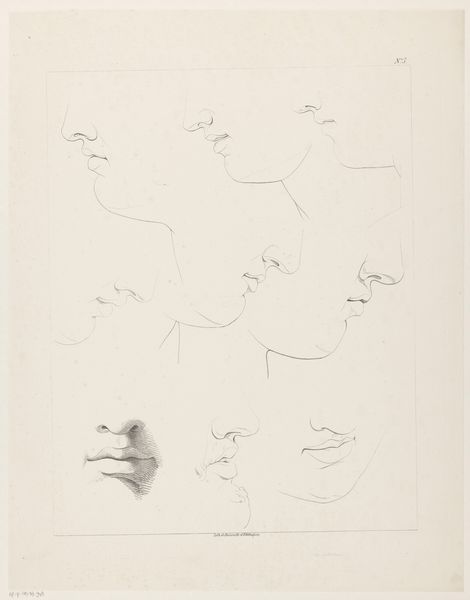

Editor: Here we have "Five Studies of Noses, Mouths, and Chins" by Jean Augustin Daiwaille, created between 1820 and 1826. It's a pencil and graphite drawing. What strikes me is how academic and almost scientific these studies are; like a page out of a textbook. How would you interpret this work? Curator: What I find interesting is how this sketchbook page highlights the institutional frameworks of art education in the 19th century. These types of exercises were common practice in academic art training, designed to instill an understanding of proportion and idealized forms. This also indicates the development of art appreciation as it was available at the time to view or for the purposes of being able to depict them to sell. Editor: So it was really about learning the rules, rather than individual expression? Curator: Precisely. Consider how art academies operated. They promoted specific aesthetic ideals. Think about the market, the patronage system that favored Neoclassical or Romantic portraiture at the time. Skillful rendering of features was prized. What function do you think that fulfilled in society? Editor: Perhaps to portray subjects in a favorable or ideal manner? Or for other portraitists to learn from his examples? Curator: Yes, portraiture reinforced social hierarchies, constructed identity, and perpetuated status through representation. This sheet then speaks to art's role within this complex visual economy. What kind of patron may this be suitable to, with such an affordable medium and aesthetic? Editor: It's fascinating to consider how seemingly simple drawing studies can reflect larger social and political dynamics! Now I look at the sketchbook, and it's less neutral to me. Curator: Exactly, these academic exercises participated in a much broader visual culture! Examining these 'fundamentals' makes one consider the very building blocks of that visual culture. It goes to show how the seemingly mundane can hold layers of meaning when viewed within its historical context.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.