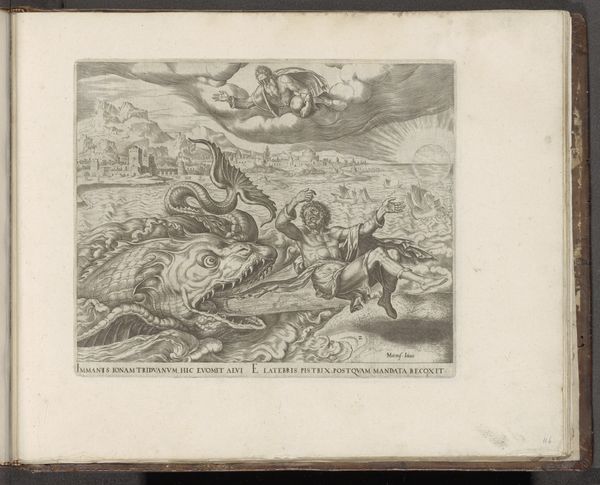

print, intaglio, engraving

#

narrative-art

#

ink painting

# print

#

intaglio

#

perspective

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 204 mm, width 249 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

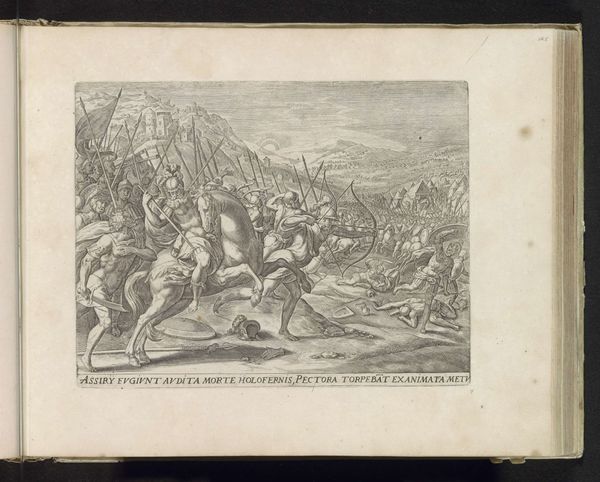

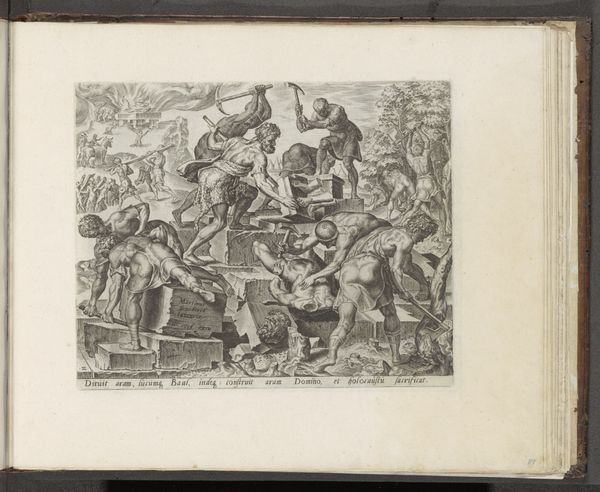

Curator: Here we have "David beheading Goliath," an engraving dating between 1554 and 1646. Editor: My eye immediately goes to the contrast – that stark depiction of brutal action set against the backdrop of a meticulously detailed, almost miniature, landscape. Curator: Absolutely. The composition cleverly uses the foreground to stage the central conflict. Observe the figure of David: his posture, almost a twisted contrapposto, emphasizes the exertion required for the act, while also cleverly positioning the subject so the beheading is central to the engraving. The use of perspective flattens the field, forcing the viewer to accept that both figures and armies have equal importance within the design. Editor: But that detail, all achieved through a subtractive process, right? Thinking about the labour intensive practice involved with creating the intaglio print process adds weight to the image. The engraving process, cutting into a metal plate to produce an image, then transferring it onto paper by hand – it speaks of craftsmanship, doesn’t it? A far cry from our digital image reproduction methods. The choice of intaglio print transforms what could be simple illustration to crafted artwork. Curator: Indeed, but let's not ignore the semiotic implications. The light emanating from the distant, heavenly body acts as an indicator of divine endorsement of this grisly victory of the underdog. Even the placement of the rainbow suggests an allegorical meaning in a society which, although experiencing advancements, remained theistic. Editor: Sure, I agree the theological symbolism is potent but also interesting to see this rendered using fairly advanced production. The printing of biblical scenes provided some agency to those producing the prints, it provided a living wage for an ever growing industry – taking this narrative art into a modern industrialised age. The way in which religious stories were being commodified interests me greatly here. Curator: You are right, of course, and as our era progresses these works would allow access to Biblical tales within many European homes. Still, I find myself marveling at the complex network of lines, the play of light and shadow used to craft this arresting scene. Editor: Ultimately, whether sacred or profane, what sticks with me is the raw immediacy of this depiction alongside the tangible labour and skill involved. It underscores how artistry, materiality, and context coalesce to generate meaning.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.