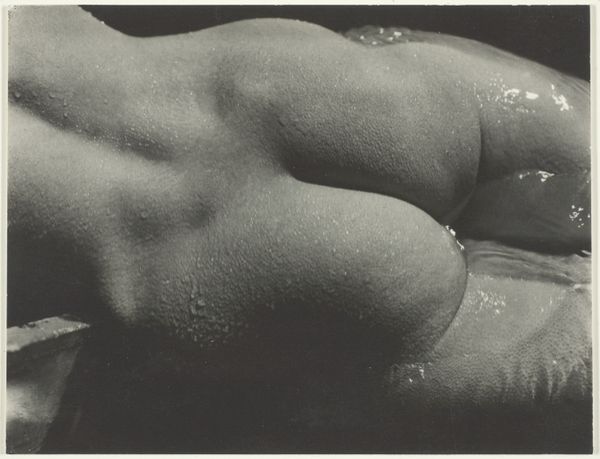

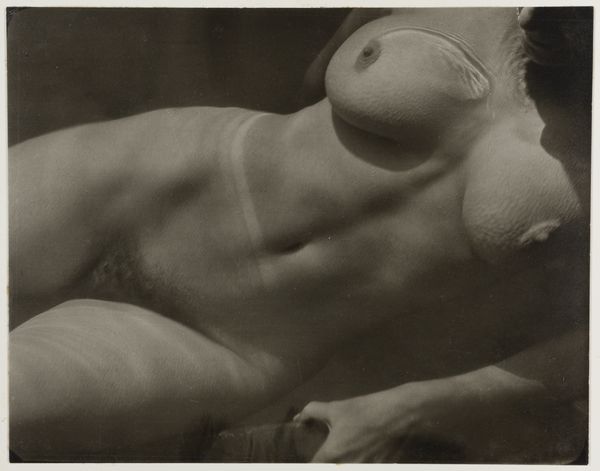

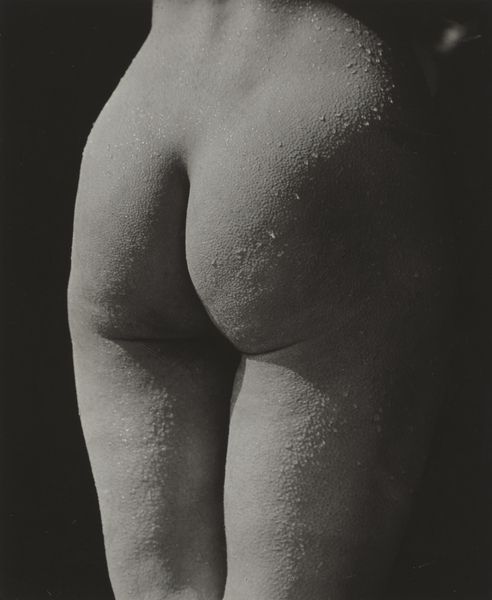

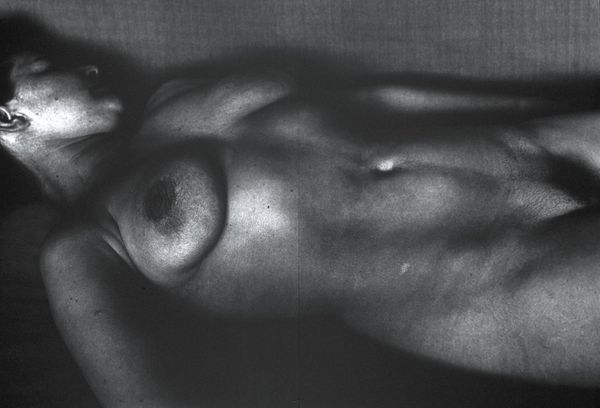

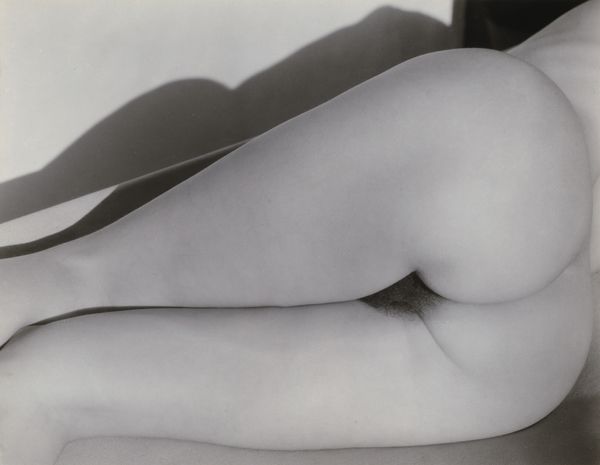

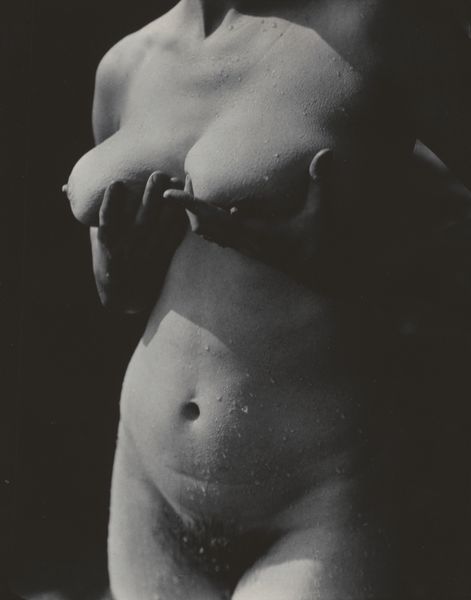

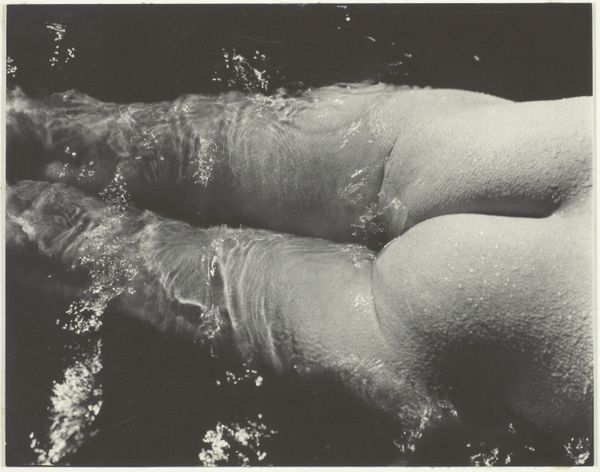

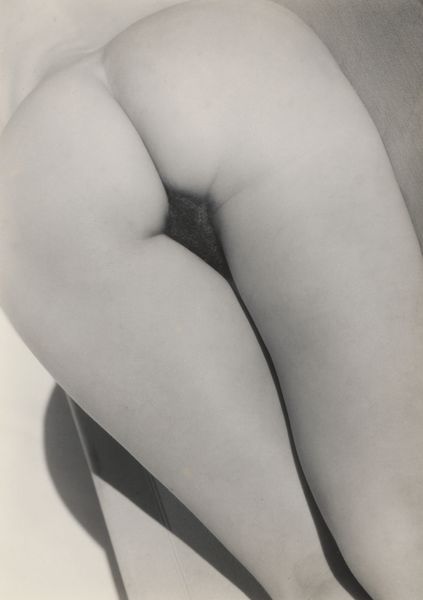

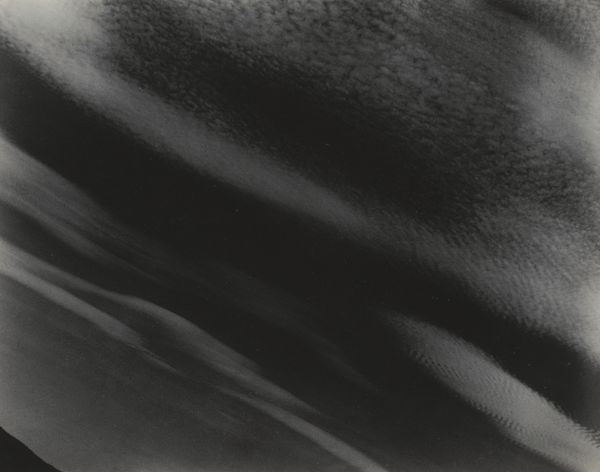

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

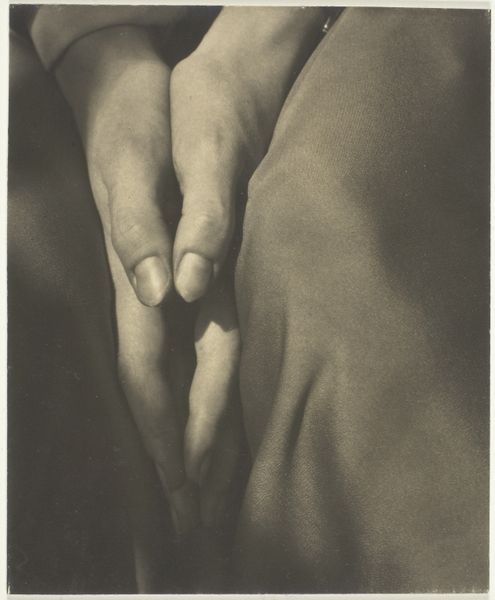

portrait

#

black and white photography

#

pictorialism

#

photography

#

black and white

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

monochrome photography

#

monochrome

#

nude

#

modernism

#

monochrome

Dimensions: sheet (trimmed to image): 9.3 × 11.8 cm (3 11/16 × 4 5/8 in.) mount: 33.5 × 26.7 cm (13 3/16 × 10 1/2 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Editor: We’re looking at Alfred Stieglitz's photograph, "Rebecca Salsbury Strand," from 1922. It's a gelatin silver print, a close-up of a nude torso. It has a very tactile, almost sculptural quality because of the stark contrast and the way light catches the curves. What do you see in this piece, particularly regarding its representation of the female body? Curator: Well, immediately, I’m drawn to consider Stieglitz's relationship with Rebecca, who was his mentee's wife, and how that power dynamic shapes the gaze within the image. In the early 20th century, artists often explored the nude form to break from traditional Victorian constraints, but often did so through a male, objectifying lens. Do you see echoes of that tradition here, or something potentially more complex given Rebecca's own artistic ambitions? Editor: I can see that tension. On one hand, it's an intimate study of the human form, highlighting texture and light. But knowing it’s Stieglitz photographing her, there's an unavoidable awareness of his perspective. Do you think the image challenges or reinforces stereotypical representations of women? Curator: That's the crucial question, isn’t it? It is crucial to understand the art world at this time was heavily dominated by men, shaping what was considered ‘beautiful’ or ‘acceptable’. Does the photograph celebrate female sensuality, or does it, perhaps unconsciously, present it as an object to be dissected and admired? The image exists in the intersection of art, power, and gender. And this is always shifting with culture. What would you hope our listeners take away after experiencing this artwork and our dialogue? Editor: I think I’d like them to walk away thinking critically about who gets to create representations and how historical power dynamics impact what we see, and how it makes us feel when viewing the female form. Curator: Precisely. Recognizing those complex layers allows us to engage with the artwork in a far more nuanced way.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.