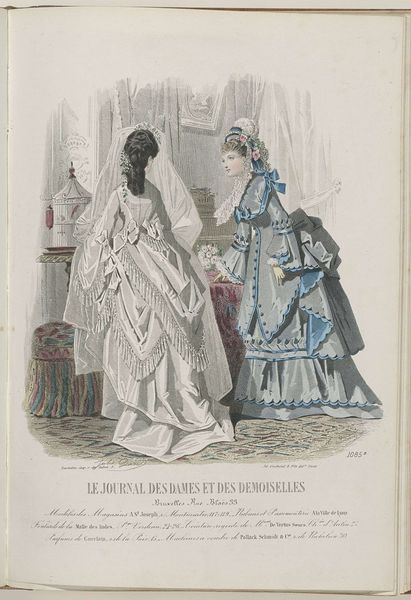

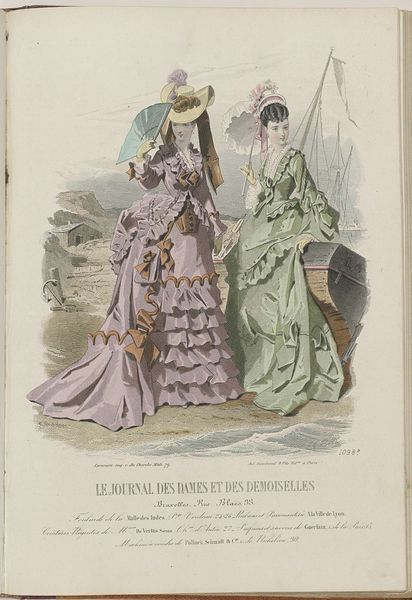

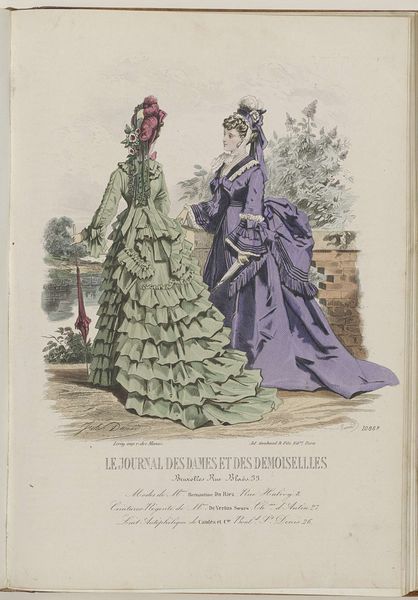

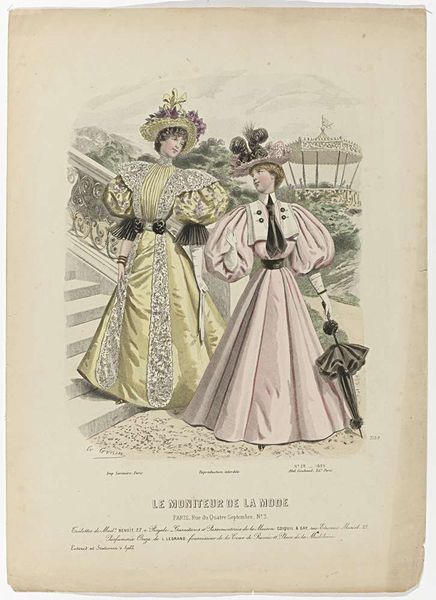

Dimensions: height 295 mm, width 200 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: We’re looking at *Journal des Dames et des Demoiselles*, a print from 1872 by Jules David, housed at the Rijksmuseum. The women's dresses are so elaborate, and the colours are exquisite! How do you read a piece like this? Curator: For me, this print opens a window onto the means of production and the socio-economic structures that shaped fashion in the 19th century. Consider the labor involved in producing these garments—the fabric, the lace, the embellishments. These weren't mass-produced synthetics; this represents specialized craftsmanship and skilled labor. Editor: Right, the process...So the image highlights not just the aesthetic, but also the massive undertaking behind each dress? Curator: Precisely. This journal served as a form of advertising, fueling consumption among the upper classes. It blurs the lines between art, craft, and commodity. The print is not simply a beautiful image, it is documenting aspiration and a level of skilled labour, from dressmaker to printmaker, that most consumers are divorced from. Editor: So you’re suggesting it's less about art, and more about the system that creates art? Curator: Not exactly. It’s both! The aesthetic value is inseparable from its context within a system of production and consumption. It challenges that traditional boundary by displaying what high art meant at the time: material display that took extreme human labour. Where did the materials come from? Who spun and wove them? Where was the lace produced, and by whom? Consider this image in relation to child labour... It may shift your perspective. Editor: That gives me a lot to think about. Seeing it that way makes me consider my own consumption habits, even now. Thanks! Curator: Exactly, by observing the means of material production back then, perhaps we can bring those obscured elements into view again, today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.