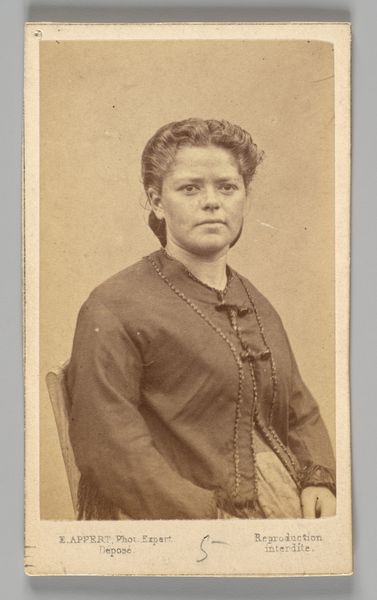

![[Member of the Paris Commune: Laure, cantinière, à perpétuité] by Ernest Eugène Appert](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzLzdiZmI3NGRlLWY4NjQtNDdmNC1hZTBmLTQ5ZDVkMjJlOTk0Zi83YmZiNzRkZS1mODY0LTQ3ZjQtYWUwZi00OWQ1ZDIyZTk5NGZfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

[Member of the Paris Commune: Laure, cantinière, à perpétuité] 1871

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: Image: 3 5/8 × 2 1/4 in. (9.2 × 5.7 cm) Mount: 4 1/8 in. × 2 1/2 in. (10.4 × 6.3 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: Here we have Ernest Eugène Appert's "Member of the Paris Commune: Laure, cantinière, à perpétuité", a gelatin silver print from 1871. I'm struck by the directness of her gaze, and the details in her clothing – it makes me think about the role of women during the Paris Commune. What stands out to you in this piece? Curator: For me, this image demands a focus on its production and circulation. The materiality of the gelatin silver print itself tells a story. This wasn't just an artistic portrait; it was likely used as evidence, as a tool of political repression after the Commune was crushed. The “Phot. Expert” stamp, Appert's self-declaration, reveals how photography was becoming a form of bureaucratic authority, contributing to documentation used for political ends. Notice how it highlights labour – both in the process of capturing the image, and in representing the sitter as part of that labour, her service, “à perpétuité”? Editor: That's a really interesting point. I hadn't thought about it as a document used in political repression, but that makes a lot of sense given the context. What would a "cantinière" typically do during that time? Curator: Cantinières like Laure typically provided supplies, and often also functioned as nurses. Appert might be drawing a clear link for audiences of his photographs between that role and active militant participation to discredit both the Commune, and by extension, female participation in broader political and social life. How the image was circulated and consumed within Parisian society matters more to me than some idealized romantic narrative. Editor: I see what you mean now; thinking about how photography was used to create a record, and in this case, potentially a record to punish. I’ll never look at these nineteenth-century portraits the same way. Curator: Exactly! And that's why looking at materials, process, and social context can reveal so much about even seemingly simple portraits.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.