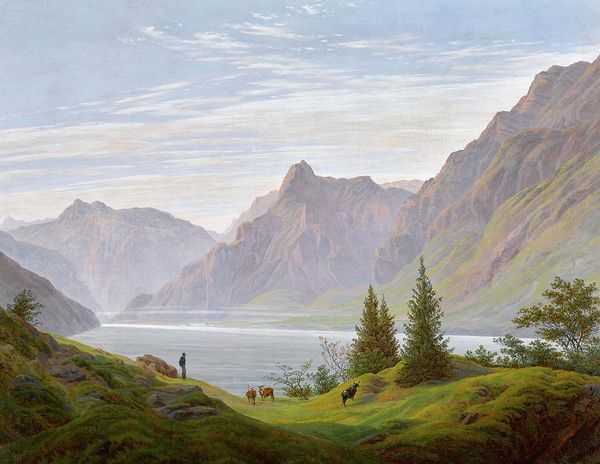

Dimensions: support: 760 x 1012 mm frame: 940 x 1280 x 115 mm

Copyright: CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED, Photo: Tate

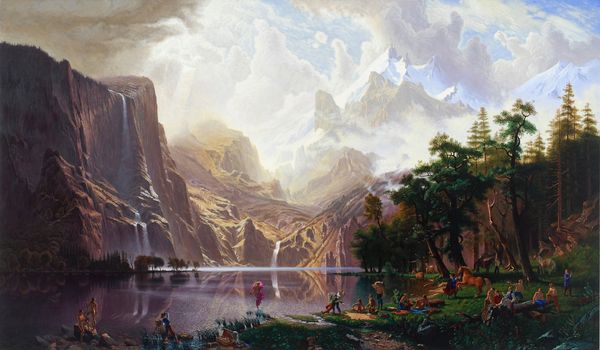

Editor: So, this is John Glover's "Thirlmere," painted sometime in the early 19th century. The way he captures light makes it feel like a lost Eden. What do you see in this piece, beyond the landscape? Curator: I see a potent commentary on land use and ownership. Glover, though celebrated for his landscapes, was deeply implicated in colonial dynamics in Tasmania. Does this idyllic scene obscure the realities of dispossession and environmental change occurring during this period? Editor: That’s a fascinating angle. So, you’re suggesting we can't separate this seemingly peaceful image from the larger historical context of colonialism? Curator: Precisely. The very act of representing this landscape as untouched naturalizes a particular power structure. What isn’t shown is often as important as what is. Editor: This makes me rethink what I initially saw. It’s much more complex than just a pretty picture. Curator: Exactly! Art often asks us to confront uncomfortable truths.

Comments

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.

tate 9 months ago

⋮

Thirlmere (formerly known as Leathes Water) is depicted here from the north. Helvellyn, shrouded in mist, is at the left and Raven Crag at the right. The house on the grassy slope in the distance is Dalehead Hall, home of the Leathes family, for whom this work was perhaps painted. Glover exhibited paintings of the Lake District from 1795 onwards and lived there for two years around 1818-20. He aspired to be the 'English Claude' and much of his work is more picturesque in character than this example. Glover emigrated to Tasmania in 1830. Gallery label, September 2004