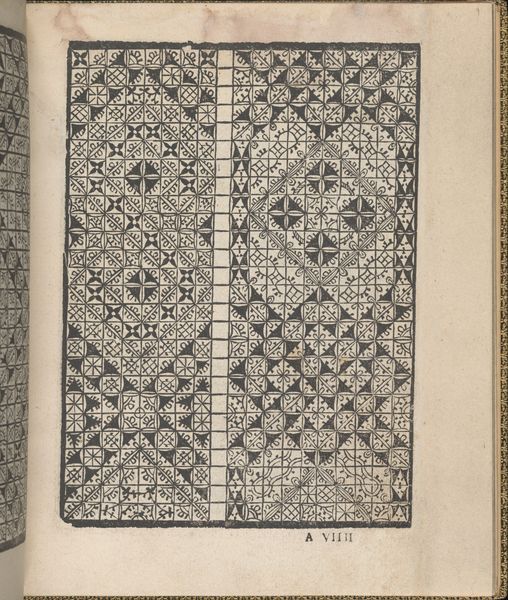

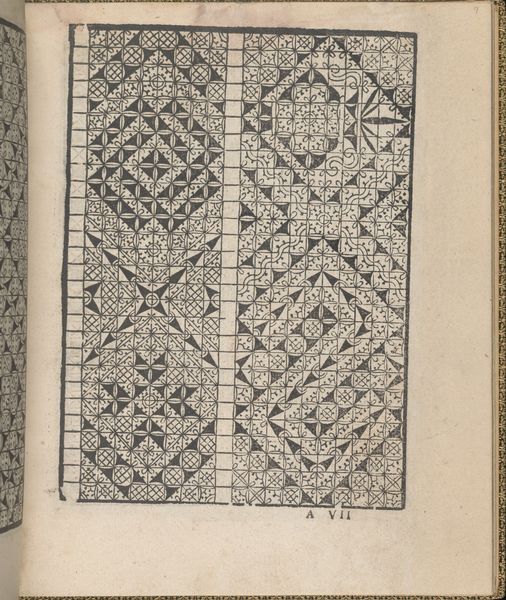

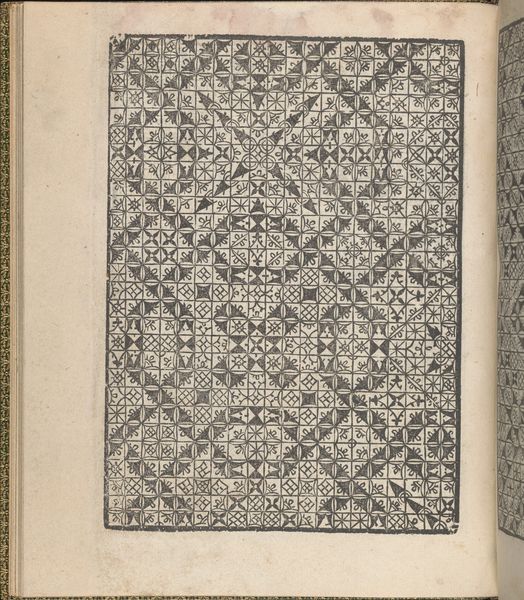

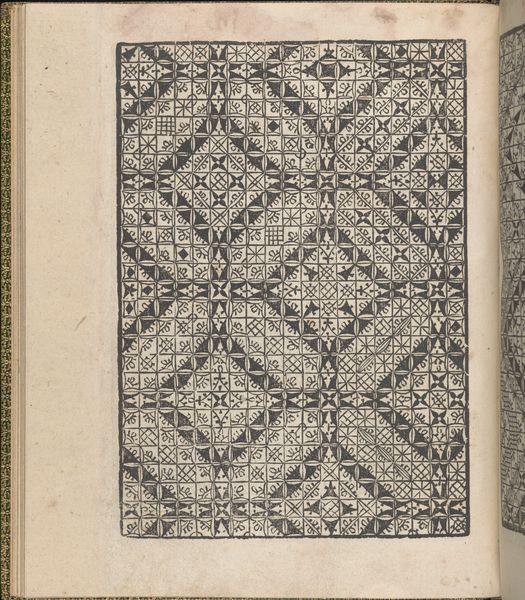

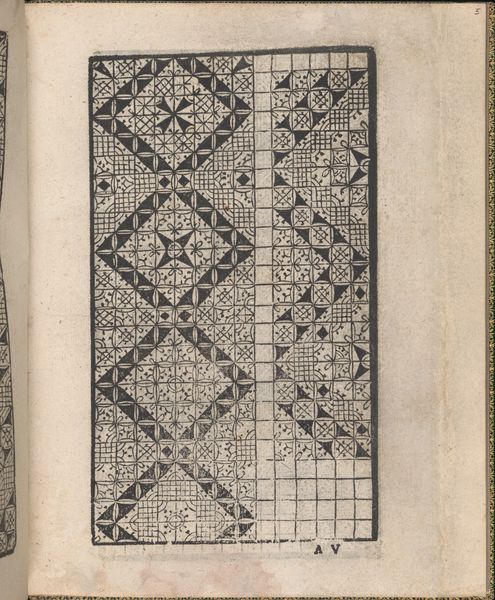

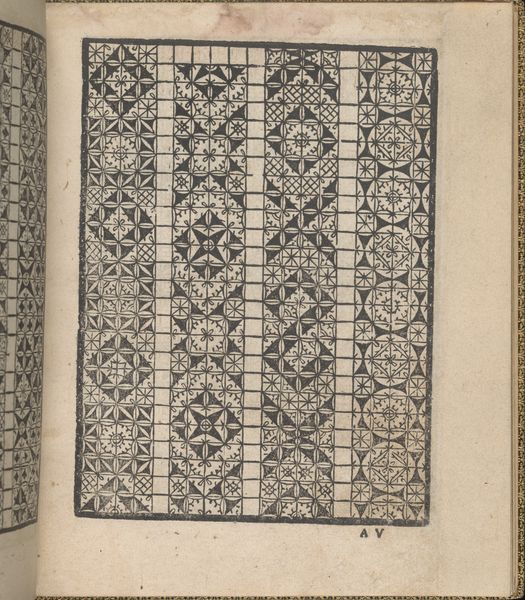

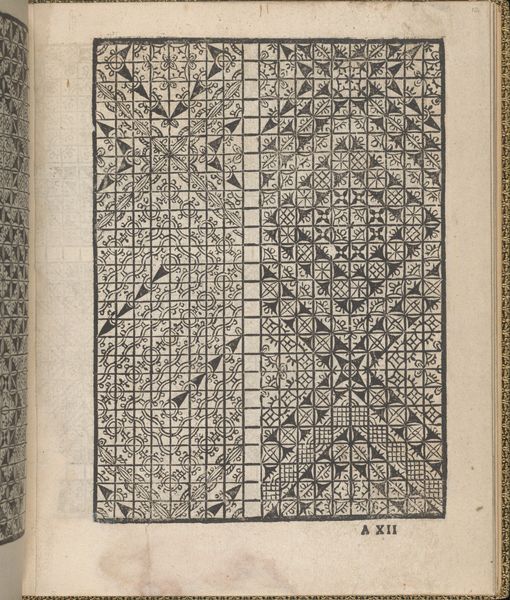

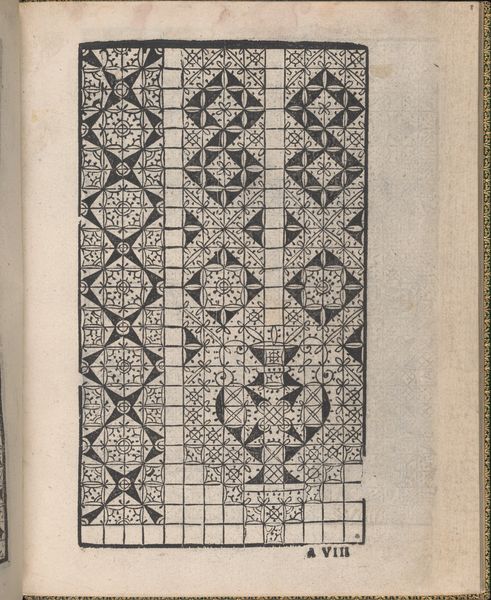

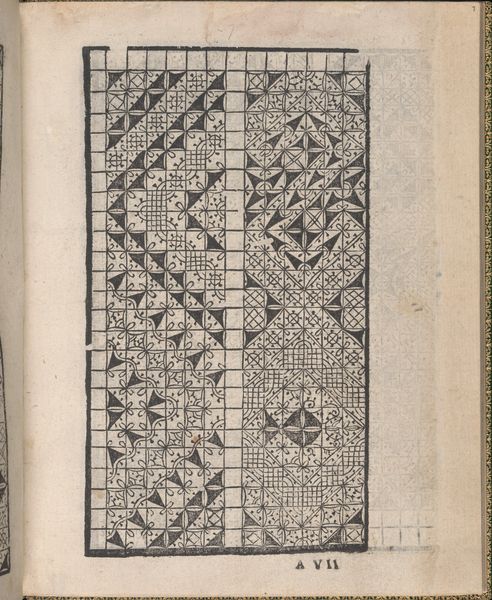

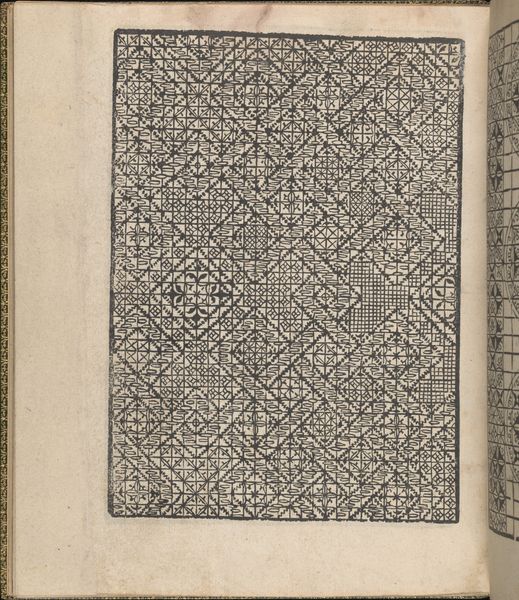

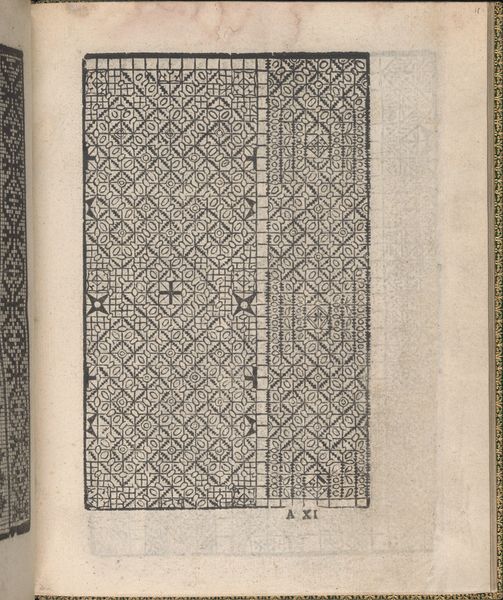

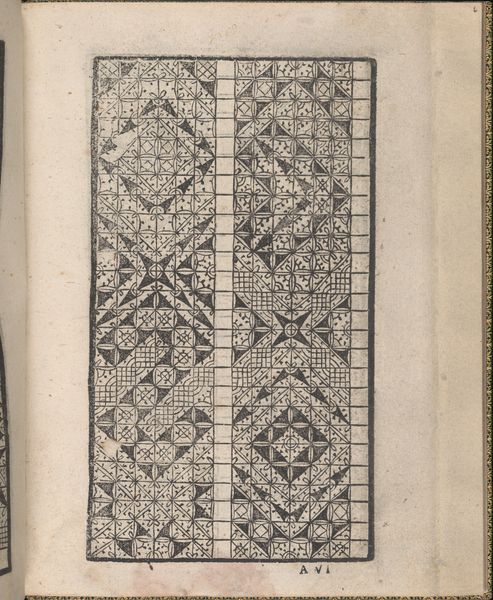

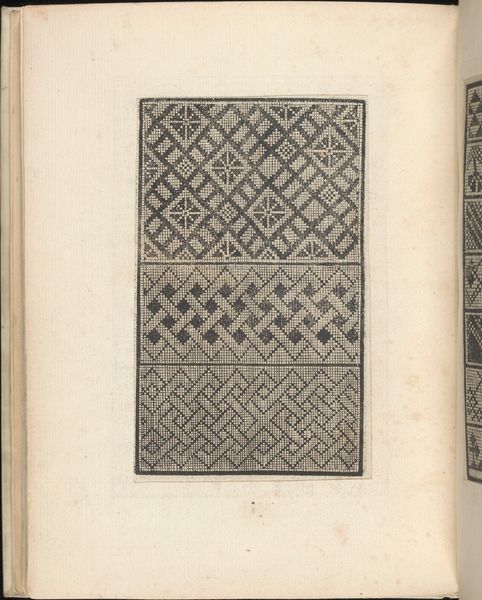

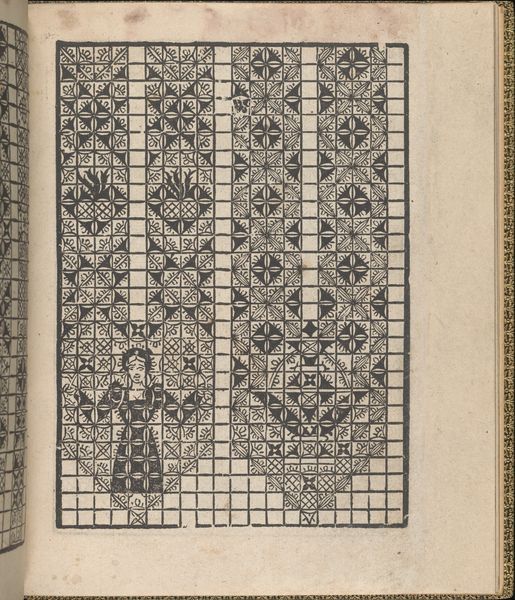

Giardineto novo di punti tagliati et gropposi per exercitio & ornamento delle donne (Venice 1554), page 9 (verso) 1554

0:00

0:00

graphic-art, print, paper, woodcut

#

graphic-art

# print

#

paper

#

linocut print

#

geometric

#

woodcut

Dimensions: 7-5/8 x 6-3/8 x 1/4 in. (19.4 x 16.2 x 0.6 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have a page from "Giardineto novo di punti tagliati et gropposi per exercitio & ornamento delle donne," published in Venice in 1554, a woodcut by Matteo Pagano. Editor: The immediate impression is one of organized labor; it feels like meticulously crafted material, black lines that demand patience and a maker truly invested in process. Curator: Absolutely. These pattern books were specifically created as guides for women practicing needlework, an art form often overlooked but crucial to the social fabric of the time. We must remember to address these pieces not merely as instruction, but cultural artefacts of labor that had societal impact. Editor: Right. Think about the physical act of carving the woodblock. It suggests a careful consideration of tools, the pressures applied, and ultimately, the embodied labor transferred to these prints on paper. Was it skilled or apprentice work, done in solitude or collectively in workshops? This informs its value. Curator: Precisely. These geometric patterns were not just decorative; they were instruments for women to engage with their own creativity and identities within very confined social spaces. How could such patterns empower those who are in difficult, constricting social contexts? Editor: And it directly connects the artistic labor of printmaking with that of needlework, often deemed separate but clearly interwoven here. By democratizing these skills via pattern prints, one type of craft spurs another type of labor and value creation. Curator: The use of pattern books invites the users into a global dialogue about beauty and art, influencing fashion and household decorations, allowing these designs to enter diverse spheres and permeate into various spaces. Editor: And yet, while intended for female ornamentation and creative labor, who benefitted materially from its production? Pagano as the publisher certainly, but exploring its function beyond aesthetics challenges our preconceived notions of artistic production in 16th century Venice. Curator: Absolutely. By observing this artwork through the lens of material production and social influence, we see that pattern books aren’t static design manuals, but nodes of dynamic, creative exchange. Editor: A point well made. This changes our outlook towards the labour of both artmaking and craftsmanship.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.