drawing, print, paper, engraving

#

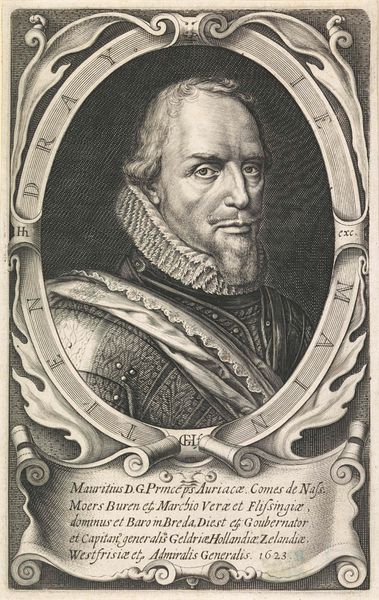

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

sculpture

#

paper

#

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: 450 × 330 mm (image); 450 × 334 mm (plate); 456 × 338 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have Paul Pontius’s engraving dating from 1632, titled "Philip IV, King of Spain." It’s a rather formal portrait, currently residing at the Art Institute of Chicago. Editor: My first impression is the stark contrast between the face and the dark clothing—it gives him an almost spectral appearance. It's hard to get a sense of the man behind all those royal symbols. Curator: Indeed. It's an image steeped in the visual language of power. Consider the elaborate collar, the ornate chain, even the draped curtain in the background, all reinforcing his status. This portrait emerges in a moment of Spain's imperial decline during the Thirty Years War, even. Editor: Absolutely, the symbolism feels weighty, almost oppressively so. What I find interesting is the choice of certain repeated forms and imagery. The squares seem to suggest concepts of order, duty and authority, the repeated circles giving us motifs suggesting continuity. Curator: Pontius was working from a portrait by Peter Paul Rubens, so that would speak to Rubens' position as a painter of royal imagery throughout Europe. And in a sense, this engraving disseminated that imagery even further. Editor: That explains a lot. You see how even in a more accessible medium like an engraving, the goal is still to reinforce that royal presence through visual symbolism. He looks every bit the detached, divine ruler. The chain links together circles that remind me of stylized suns. Is there any connection? Curator: The sun was a common symbol associated with monarchy. You're right to consider that symbolism. Louis XIV adopted it soon after. This image participates in that construction of absolute authority. The portrait was more about conveying an idea of kingship rather than portraying a person, particularly within the world of absolutist power that emerged from the peace of Westphalia following the war, giving royalty and the institution greater prestige, and of course political weight in shaping the rest of Western civilization. Editor: Right, the psychological distance it creates. Even four centuries later, one gets the sense that those symbols sought to create that barrier, so people perceived the King as less of a man, and more of a divine presence. I appreciate this print far more knowing the socio-historical dimensions of its making. Curator: Exactly. Examining such a work reveals so much about the historical, social, and artistic practices of the 17th century. Editor: Agreed. This piece reveals so much about the language of visual culture in communicating ideas of power, even today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.