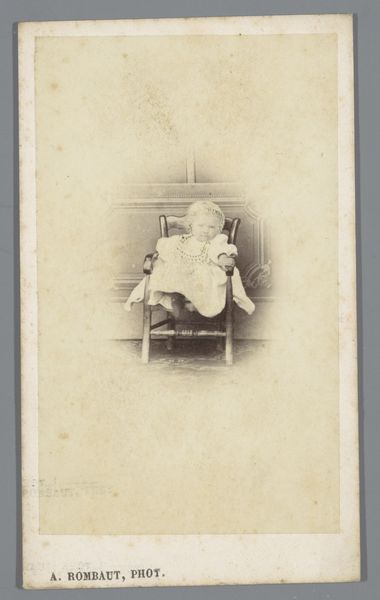

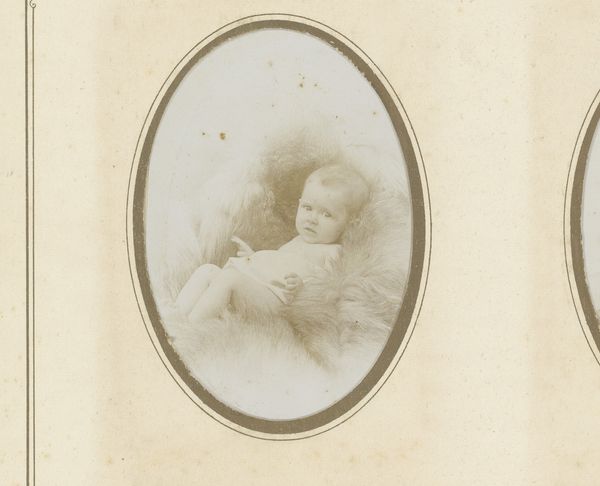

Post-mortemportret van een onbekende jongen, gekleed in een matrozenpak 1858 - 1905

0:00

0:00

photography, albumen-print

#

portrait

#

still-life-photography

#

photography

#

momento-mori

#

albumen-print

#

realism

Dimensions: height 103 mm, width 61 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is a post-mortem portrait of an unknown boy dressed in a sailor suit, an albumen print created between 1858 and 1905 by Fernand Cairol. Editor: The first thing that strikes me is its incredible sadness, an innocence suspended in a photograph whose stark tones do nothing to mask the reality of loss. It’s also undeniably unsettling. Curator: Post-mortem photography became a relatively common practice in the Victorian era. With high infant mortality rates and limited access to photography, it was often the only lasting image a family would have of a deceased child. Editor: Right, it speaks volumes about both Victorian attitudes towards death and also the democratization of photographic practices—although seeing it through today’s sensibilities around mourning and images of the dead complicates how we perceive it. Looking closer, that stiff sailor suit seems less celebratory and more like a kind of forced performance. Curator: The sailor suit itself is significant. It became fashionable for children after Prince Albert Edward, the future Edward VII, was painted wearing one in 1846. These outfits symbolized belonging to a modern, maritime power and instilled patriotism even in childhood. Editor: A poignant, and frankly, disturbing detail when contextualized with the subject’s death. We’re seeing symbols of power, modernity, and national pride superimposed onto a corpse. What sort of message does this confluence of symbols intend? Curator: I suspect it was likely a mix of sentimental preservation and societal expectations. The photo normalizes the tragedy while offering some level of dignity within the structured world of Victorian mourning. Editor: It makes me wonder, though, about agency—or the lack thereof—afforded to this child. Was this performance, this final presentation, as much about consoling the parents, perhaps, or society’s own anxiety about mortality as about memorializing a child? How does something intended as personal and familial then turn into a signifier of broader social anxieties? Curator: Well, isn’t that the core of any image? Its ability to function within an incredibly intricate set of social codes and expectations while also evoking individual responses? Editor: Absolutely, and that’s what makes it such a powerful object—a vessel brimming with personal grief and potent historical symbolism that keeps pushing us to confront uncomfortable truths about death, remembrance, and the stories we tell ourselves. Curator: Indeed. Examining this work allows us to reflect on photography's historical function in shaping memory, but it can also prompt reflections on how we deal with loss and how the meaning of images change across different eras and audiences.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.