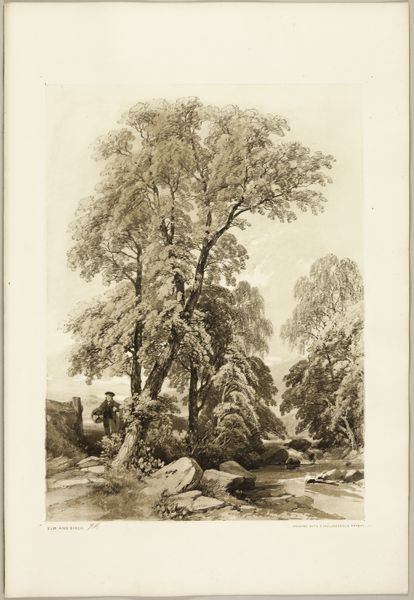

Fotoreproductie van een schilderij van een liggende man in een landschap door Julius Mařák 1850 - 1900

0:00

0:00

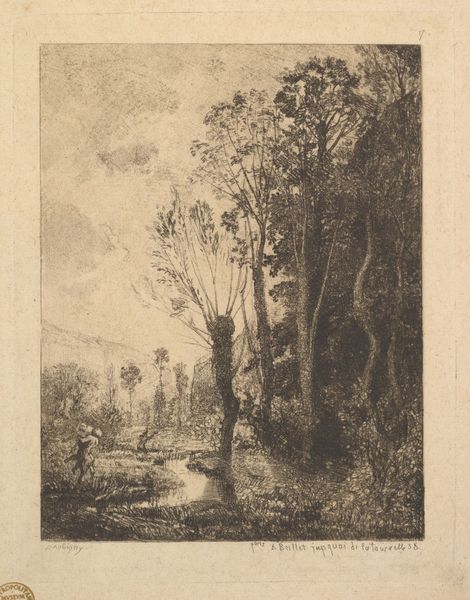

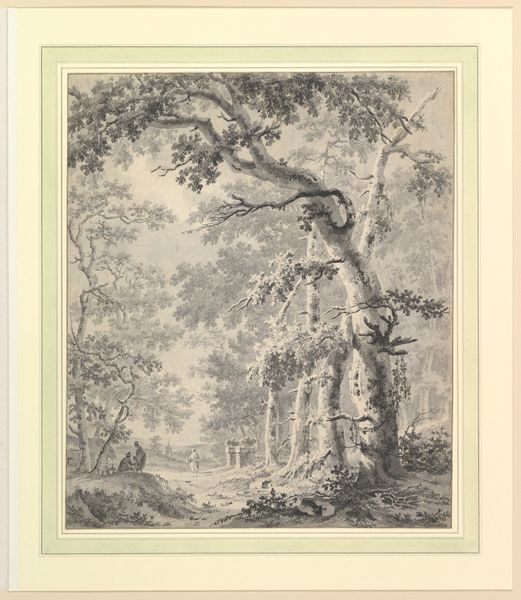

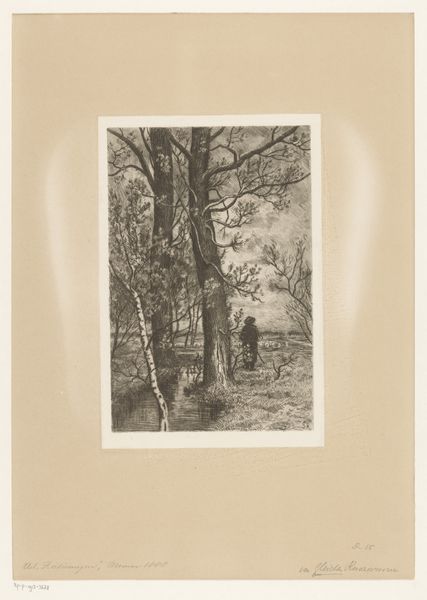

Dimensions: height 138 mm, width 98 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

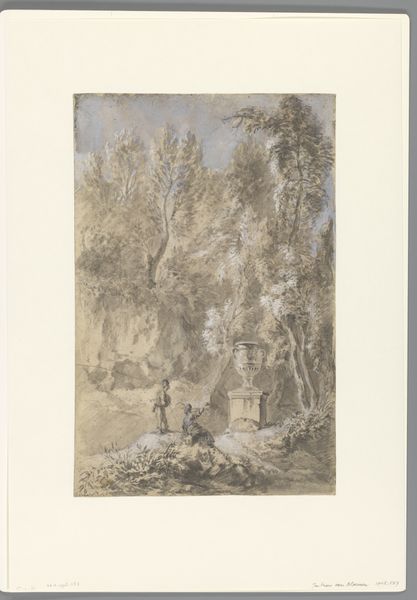

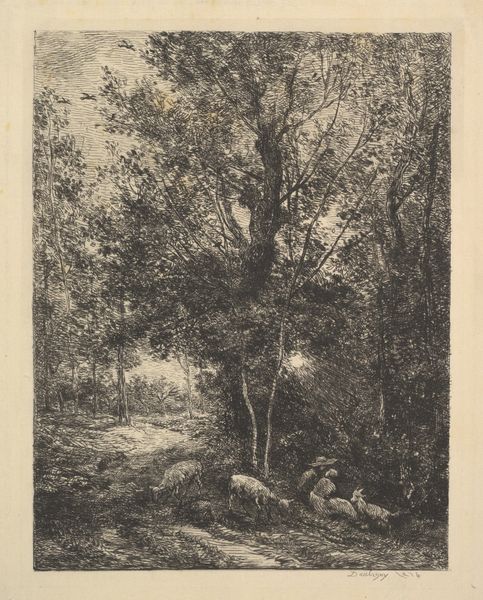

Curator: There's a peaceful quality to this work; almost melancholic. What do you see first? Editor: That central figure, prone amongst the roots of those trees, it speaks volumes. We're looking at what's recorded as a photographic reproduction of a drawing by Julius Mařák. Charcoal and pencil work together to make what can only be described as a dreamy clearing, and it must have been made somewhere between 1850 and 1900. Curator: Absolutely. And notice how the artist directs the gaze – we enter this scene on a path between those jagged rocks, past thick vegetation, towards that solitary man. He’s positioned almost centrally, suggesting he’s vital to grasping the piece as a whole, yet also hidden and at rest within it, perhaps weary with the modernising world closing in? Editor: Yes, the Romantic spirit is definitely palpable. These visual motifs were, for so many, carrying considerable cultural weight. Solitude in nature became symbolic of withdrawal from the social changes of that century, of the kind artists and poets especially felt the need to physically enact. Here, Mařák shows that retreat literally. It's all light and dark, soft lines with such an introspective quality that draws one's own thoughts in. Curator: This speaks to the rise of landscape art’s importance within national artistic expression too. You get the sense here of the landscape operating as more than just backdrop; Mařák captures something inherently human through our deep connection to the forest, both a resource and a spiritual domain in that era. Editor: True, you can almost smell the damp earth. So much Romantic era landscape depiction in the public gallery system served the purpose of building and uniting people. Even as rapid industrialisation blurred what any of that meant. And how we were supposed to "feel". The lone figure in nature became a visual shorthand, one easily decoded. I'm reminded of how Caspar David Friedrich mined similar landscape conventions, and how radical a strategy that had already become. Curator: It's curious, the photograph gives the impression of something old and preserved… even ghosts contained in this liminal forest. The texture and tones communicate directly across time, almost asking what we are doing to keep the legacy of the Earth, the very notion of landscape, safe today? Editor: I think you're right. Considering this as photographic documentation also shifts the idea, making it less personal perhaps. That adds a new dimension to it when you frame it as this object *representing* the real thing. Fascinating how a document of art accrues its own sense of symbolism too, doesn't it?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.