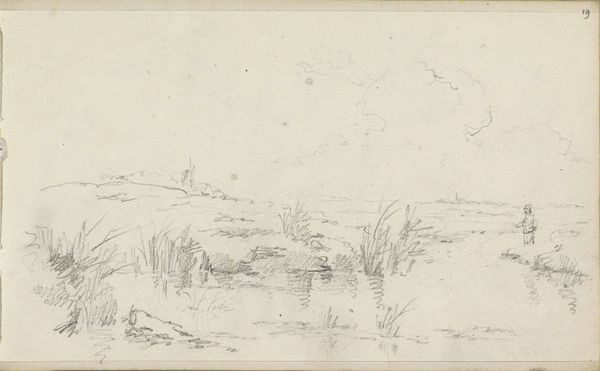

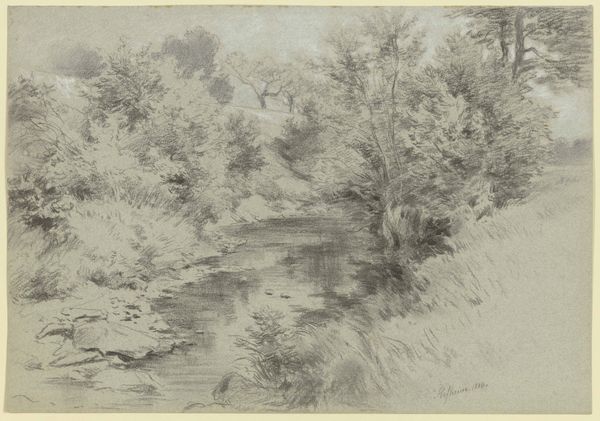

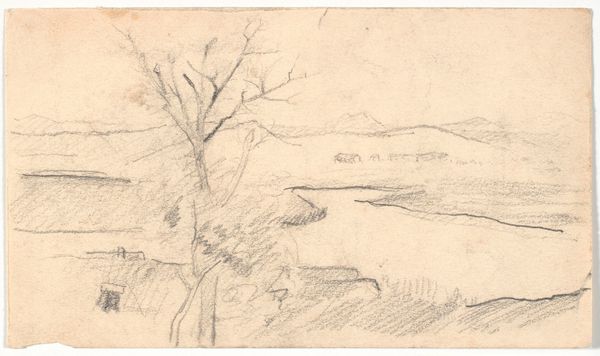

drawing, pencil

#

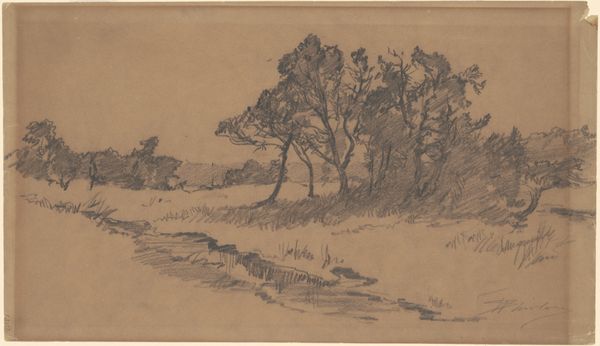

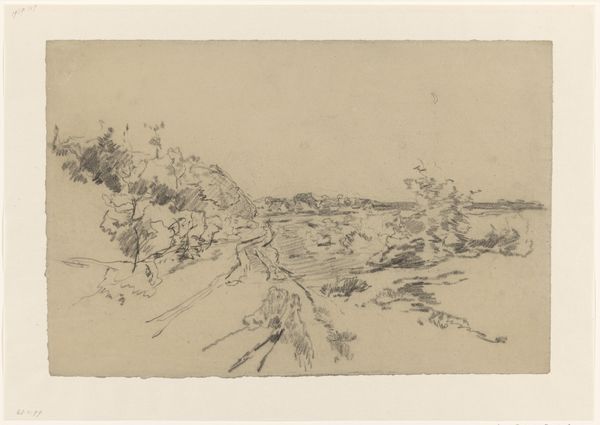

drawing

#

landscape

#

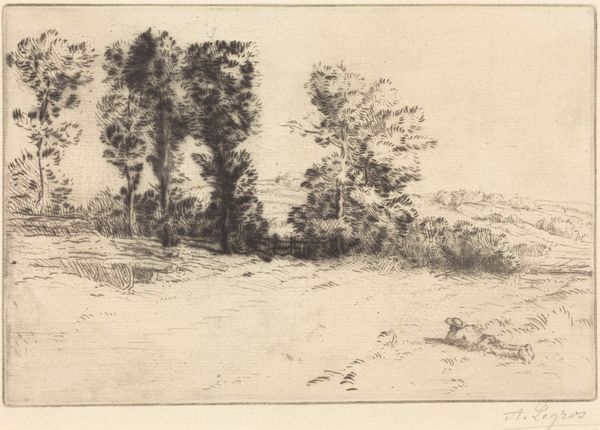

etching

#

romanticism

#

pencil

#

watercolor

Dimensions: overall: 18.2 x 27.5 cm (7 3/16 x 10 13/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Here we have Carl Gustav Carus’s "A Path through Fields near Leipzig," created around 1812, rendered in pencil and watercolor. What is your first impression? Editor: Somber, almost austere. It’s a muted palette, dominated by grays and tans. I’m struck by how much the texture of the paper contributes; it really brings out the materiality of the piece. It’s very subtle. Curator: Yes, subtlety is key. This piece embodies a particular Romantic sensibility, reflecting a longing for communion with nature. Consider the path, winding into the distance, an invitation perhaps for the viewer to consider their own path in life. Leipzig itself, as a burgeoning industrial center, would have been the implied contrasting experience, highlighting the spiritual need for rural, reflective experience. Editor: That resonates with the era. What interests me is how Carus builds the landscape with these repeated marks—hatching and cross-hatching to create depth and volume. You can practically feel the roughness of the field under your fingers, as if the drawing becomes a kind of manufactured substitute for material and tactile encounters with an environment that the industrial revolution began to erase from peoples lives. It isn’t just what the landscape *means,* it’s how the drawing actively, materially reproduces its textures and forms. Curator: Absolutely. And it's through those artistic renderings that we sense the symbolism. The seemingly ordinary path, under Carus's hand, transforms into an introspective journey, a visual metaphor for the spiritual quest and connection with nature's divinity so important for Romantic thinkers. Even those modest clumps of grass participate in an elevated form of meaning-making. Editor: Indeed, the lack of high-keyed color forces one to really focus on line and texture—how Carus uses relatively humble materials, pencil and watercolor on paper, to suggest a vast and emotionally significant landscape. One really comes away thinking about his labor: how long he worked at the sketch, and what sort of physical, sustained communion with the land he actually performed through that labor. Curator: Thinking of Carus now, I reflect on the enduring human need to imbue our surroundings with symbolic meaning, and art's vital role in making visible our complex relationship to nature. Editor: And I appreciate how this drawing underscores the potential in the everyday – seeing how the very act of mark-making and its specific material conditions help mediate how we construct that meaning, even today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.