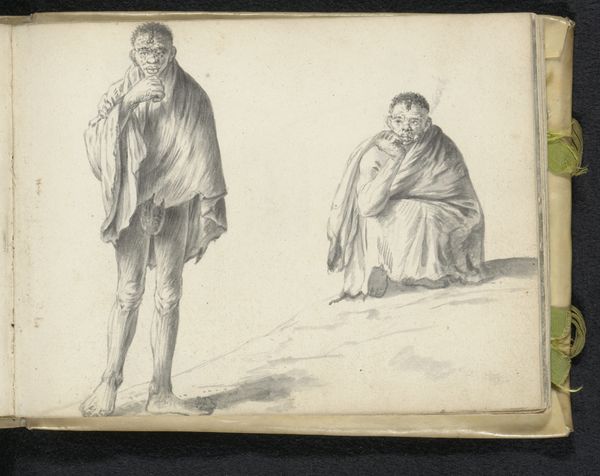

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

#

pencil sketch

#

coloured pencil

#

pencil

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: height 148 mm, width 196 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

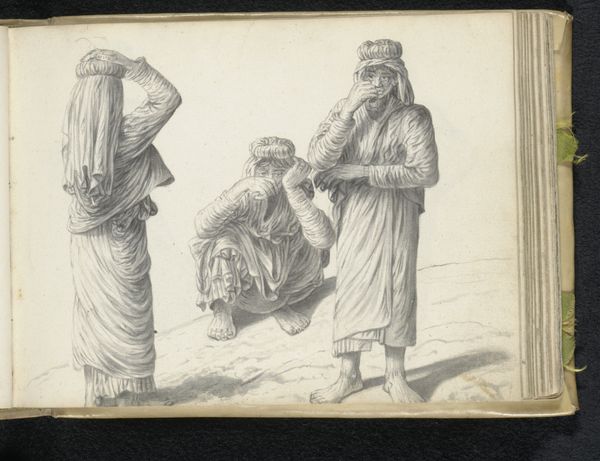

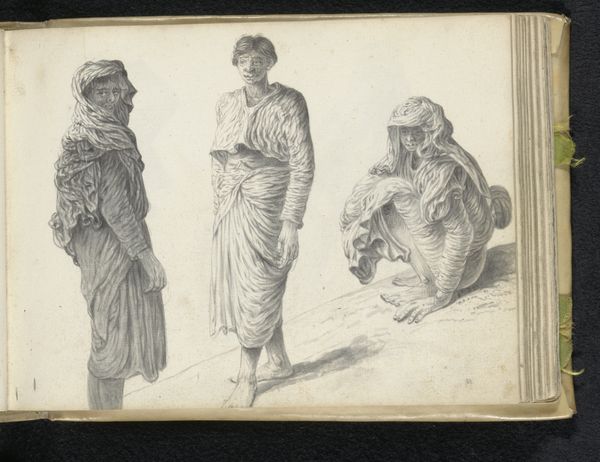

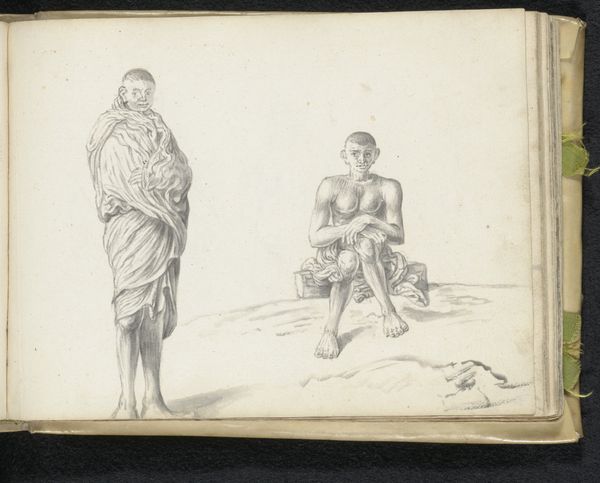

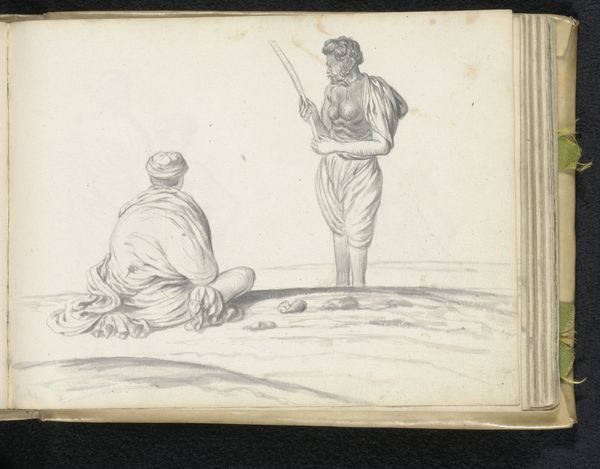

Curator: Esaias Boursse's pencil drawing, "Two women; one standing, one squatting," completed in 1662, presents us with a deceptively simple scene. Editor: Deceptive is right. My initial response is one of stark contrast—the verticality of one figure clashes with the grounded posture of the other. A palpable tension arises from this opposition. Curator: Indeed. Boursse masterfully employs line weight to distinguish the figures, adding depth and texture to their garments. The interplay of light and shadow, especially on the squatting woman's drapery, invites closer inspection. Note how his skilled rendering brings out the fabric's folds. Editor: Yet what do these lines signify within their social context? Are they studies of class, labor, perhaps even resistance? The standing woman's crossed arms might be read as defiance, while the other seems resigned, almost blending into the landscape. Curator: I appreciate that interpretation. However, I find myself drawn more to the artist's formal choices. Look at the composition—the balance created by the positioning of the two women and how the landscape, simple as it may be, gives an architecture to the portrait. Boursse created such dimensionality and the drawing seems to move with each pencil stroke. Editor: I concede that his rendering is exceptional, but for whom? What biases were imprinted onto the subjects? And furthermore, the setting feels stark, a non-space, which is itself a significant detail that says so much. Who were these women, and what would a decolonial lens reveal about their untold stories? Curator: Fascinating points. Semiotically, it might signal their alienation. Boursse created an almost unbearable symmetry in the dichotomy. This reinforces the visual strength. Editor: Right. Perhaps their otherness in the context of 17th-century Dutch society made it feel alienating to observe such stark conditions of early modern labor or even of early modern Dutch life. Curator: It’s through a nuanced approach to art history, that our understanding of this artwork opens up. Editor: It's vital we interrogate historical representation—revealing silenced perspectives while admiring skillful aesthetics.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.