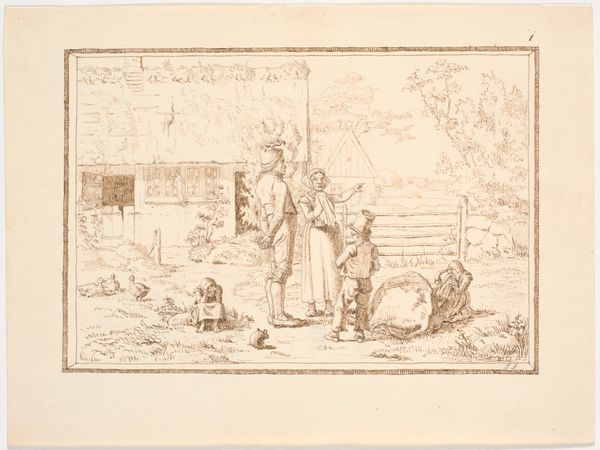

Boslandschap met een boerin en haar gezin voor een stal 1819

0:00

0:00

johannchristopherhard

Rijksmuseum

drawing, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

#

romanticism

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 200 mm, width 265 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Before us, we have a work titled "Wooded Landscape with a Peasant Woman and her Family in Front of a Barn," a drawing created in 1819 by Johann Christoph Erhard. It resides here in the Rijksmuseum. The work is crafted with ink on paper. What strikes you first about it? Editor: Well, I am struck by the intimacy. The tight composition of the peasant family huddled near their barn gives it a familiar feeling. It makes me think about the narratives constructed around agrarian life. It looks quiet, perhaps even melancholy. Curator: I agree. Melancholy is an excellent descriptor. Look at the iconographic language at play: the figures positioned so centrally. Consider the woman’s direct gaze – a clear message about the virtues and hardships of rural life. I sense both weariness and determination. Editor: Absolutely, it is a clear romanticizing of rural life and peasantry. However, looking at it with modern eyes, I start to wonder who this image was actually made *for.* Was it for the urban upper class who sought romantic images of what they perceived as a simpler, pastoral existence? I am keen to know the art world context that would allow an image like this to be sold and received in society. Curator: Indeed. That context is key. Romanticism was then in full flower, seeking to recapture a sense of purity and connection to the land, one perceived to be vanishing amidst industrialization. This family becomes a symbol – almost an emblem – of that idealized past. It speaks to the psychological need for an untainted existence, regardless of realities. Editor: And the scale works too, the humble scene portrayed in an intimate drawing underscores that authenticity. It is as if it has always been that way, an established order. It reinforces an assumed social contract and quietly justifies the existing conditions for both patron and viewer. What looks like just a portrait then does an immense amount of subtle work when one considers how power and money circulated at the time. Curator: Precisely, we see a convergence of idyllic imagery serving very worldly purposes. The image operates at once on a representational and symbolic level. Editor: It makes me reconsider how images of the "common" person become a tool. By placing it in this gallery we've changed its function too, the social context now altered by institutions such as our own. Curator: True, these pieces acquire fresh symbolism over time, echoing past eras while reflecting today's perspectives. Editor: It prompts so many more questions about representation, doesn't it? Curator: It truly does, I agree, making Erhard’s work both beautiful and complex.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.