Copyright: Public domain

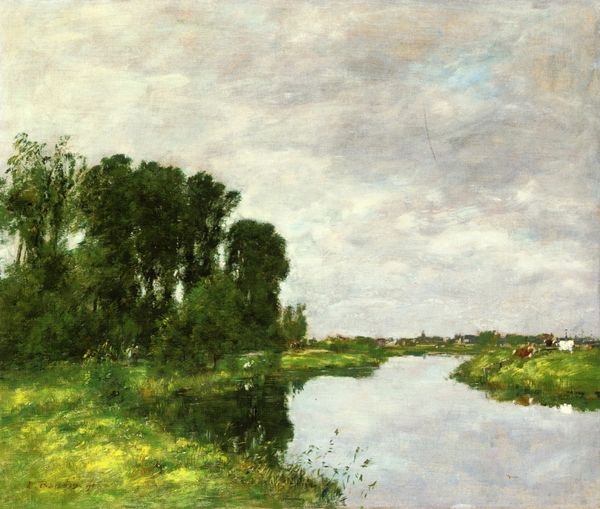

Curator: Here we have Charles-François Daubigny’s "Cattle on the Bank of the River," an oil painting completed in 1872. Editor: It's beautifully serene. The soft, diffused light and the calm river evoke such a peaceful feeling, like stepping into a memory. Curator: Absolutely. Daubigny was a key figure in the Barbizon School, and this piece exemplifies their commitment to painting en plein air. Considering that, examine how he captures the transient effects of light on the water and foliage. It's fascinating how the Impressionists built upon this direct engagement with nature. Editor: Yes, his technique really captures the ephemerality of the moment, a very modern sentiment for the time, turning away from purely history painting. You can almost feel the humid air, sense the quietude. The inclusion of the cattle and the figures, almost obscured within nature, hints at themes of humans as a minor part of the ecosystem, coexisting rather than dominating the landscape. This intersects with environmental consciousness and social roles within rural life. Curator: It does prompt a reconsideration of labor too. Think of the materiality of the paint itself – ground pigments combined with oil. It becomes a form of manual work when applied so deftly to evoke nature. The entire tradition of landscape painting relied on very specific resource chains, extraction of the pigment, canvas production. Editor: A compelling point. It underscores how landscape painting is inherently linked to our relationship with the environment, our intervention in it. And Daubigny’s choices – the loose brushwork, the avoidance of a highly polished finish – those could be interpreted as a subtle acknowledgement of the inherent, untamed nature he portrays. The composition pushes us to consider the gendered experience of rural existence; those are likely female figures under the tree. Curator: Considering the consumption of such imagery, too, becomes significant. It fueled, perhaps, a romantic idea of rural life which obscures its harsh realities. The artistic skill transforms physical labor into aesthetic pleasure. Editor: Indeed. His method, though rooted in observation, actively shapes and interprets it through a specific socio-political lens. A move away from idealized, classical landscapes in favour of portraying the present moment. Curator: And ultimately, as viewers, our role is not just to observe but to question the interplay between material, labor and nature as reflected on the canvas. Editor: Leaving us to ponder Daubigny's depiction, the role of pastoral idylls and their lasting effect on how we value land and labour to this day.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.