oil-paint

#

portrait

#

allegories

#

oil-paint

#

oil painting

#

expressionism

#

history-painting

#

expressionist

Copyright: Public domain

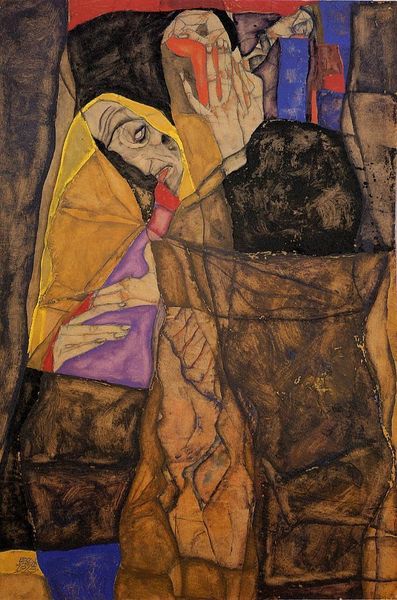

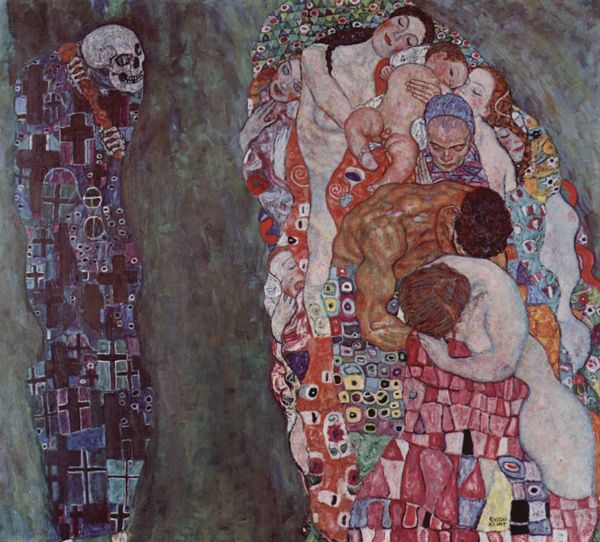

Curator: Looking at Egon Schiele's "The Holy Family" from 1913, rendered boldly in oil paint, the first thing that strikes me is the vulnerability… the fragility clinging to these figures. What about you? Editor: It’s arresting, undeniably so. Schiele pushes us immediately into a space of unease. The contorted poses, the sickly palette... it feels less like a celebration of family and more like an interrogation of it, especially within the rigid patriarchal structures of early 20th century Vienna. Curator: Interrogation, I like that. The elongated faces and skeletal hands – there’s a starkness that borders on unsettling. Schiele's own complicated family history certainly seeps into this. It is not a comfortable or simple Madonna. Editor: Exactly! It refuses the romanticized, idealized visions. This painting emerges in a period grappling with rapid industrialization, shifting gender roles, and the rise of psychoanalysis. How can we read the ‘holy family’ outside those contexts? The mother appears almost corpse-like, her face averted and weary, with no protection against the male gaze, or from an older, judging patriarch looming over. Curator: And the baby – encased in this near-suffocating orange shape—it does suggest confinement rather than comfort. The hands are there to frame and contain as well as embrace and nurture. Do you see echoes of his earlier, almost obsessive self-portraits reflected in this depiction? Editor: Definitely. His lifelong anxieties around his own sexuality and artistic expression manifest through these distorted, unsettling forms. In that regard, it might even be argued that he equates "family" with restriction itself. It begs the question – does "The Holy Family" critique oppressive social norms, or simply perpetuate them through his subjective representation? Curator: Maybe it is the rawness that grabs you. There are no platitudes here, only brutally exposed nerves. For me, "The Holy Family" remains an unfinished whisper of raw, perhaps unresolvable tension and truth. Editor: Precisely. It pushes us to actively question the family unit and its associated roles – a challenging proposition at the turn of the century. Schiele makes the spectator work, and that friction becomes the painting’s most enduring quality.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.