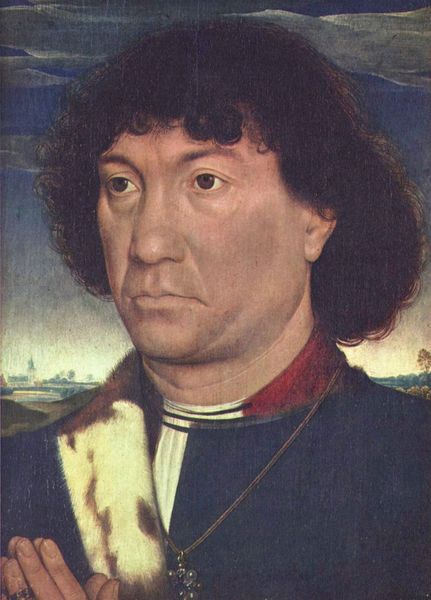

painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

Dimensions: 34.7 x 25 cm

Copyright: Public domain

Curator: This is Hans Memling's "Portrait of Jacques of Savoy," created around 1470. It's a wonderful example of Northern Renaissance portraiture, oil on panel, currently held here at the Kunstmuseum Basel. Editor: He strikes me as cautious, almost hesitant. It’s a strange mix of vulnerability and wealth presented on the face of the subject here, very skillfully executed in the texture of his robes. Curator: Let's consider the materials and process. Memling, a German-born artist working in Bruges, demonstrates incredible mastery of oil paint. He builds up layers, carefully blending to create smooth, lifelike skin tones and a sense of depth. The detail in the chain, the folds of the clothes--it all speaks to immense labour. The pigments themselves would have been expensive and sourced from far and wide; lapis lazuli, for instance. Editor: Exactly. The gold chain isn't just decorative; it's a blatant display of power and the sitter’s connection to material wealth that's inherent to nobility. But that precise and deliberate application of oil paints, while impressive, seems to ironically underscore how power is constructed, a very self-conscious performance, and so too are these historical notions of masculinity in Renaissance art. Curator: The context, as you point out, is important. Jacques of Savoy, of the House of Savoy. It speaks to a wealthy person connected to larger trade networks of its time; he certainly has the sartorial aesthetics of someone living in Renaissance-era Flanders with all the cultural sophistication implied. I am fascinated by his hands folded so gracefully in front of him, juxtaposed with the hard metalwork of the chain around his neck, perhaps representing the conflicting values present during the transition between the Middle Ages and early modernity. Editor: Perhaps... or consider how portraiture functions to solidify specific power structures during this transitional period of European history, legitimising the reign and image of ruling class. Men like Jacques became patrons, reinforcing societal expectations concerning trade, class and masculine virtue and values to further expand their influence in Europe. Curator: Yes, and Memling’s art reflects his patron’s social station. Consider the fine panel support, which also plays a role, quite literally forming the grounds of possibility in which representation itself is framed. It takes incredible craft to render a sense of self on top of layers upon layers of medium. Editor: Absolutely, examining that dynamic encourages us to view artistic labour within a social history context, which has wider political and economic ramifications when we assess class and identity and status... Curator: By understanding the artist’s skill, labor, the material choices, and the social functions surrounding his portrait, it enriches our understanding of it. Editor: Indeed, the very act of commissioning a portrait like this and Memling’s artistic choices provide further insights into larger historical and cultural structures.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.