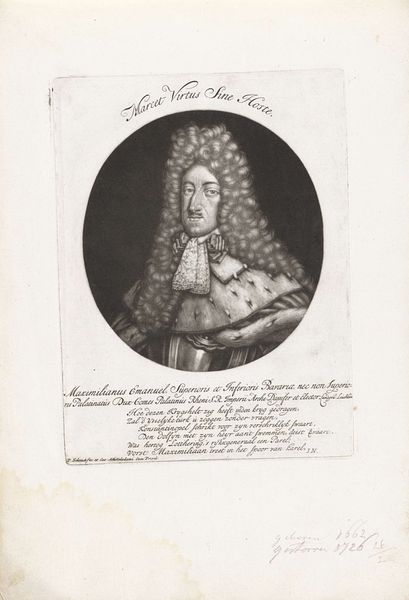

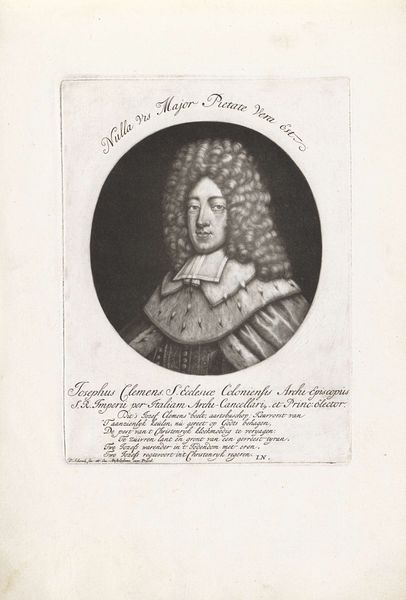

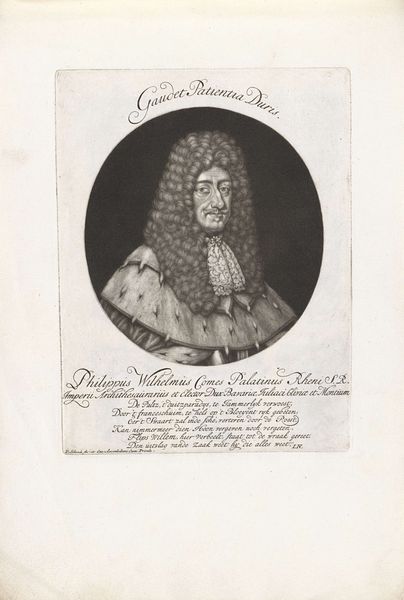

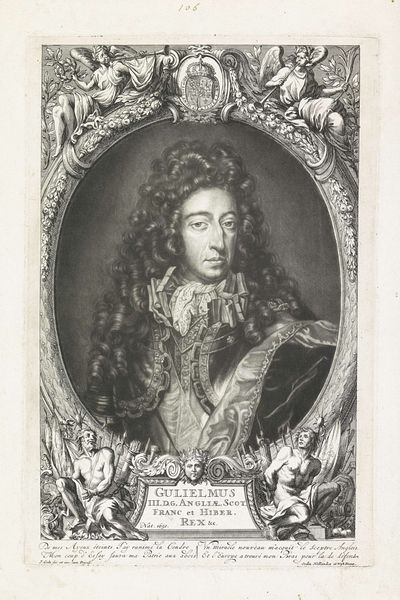

engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

old engraving style

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 185 mm, width 138 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Welcome! We’re standing before Pieter Schenk's "Portret van keizer Leopold I," an engraving, likely made between 1690 and 1713. The piece is currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Immediately, it strikes me as something that has this strange balance of the ornate and austere. It's heavy with Baroque flourish in the wig and armour, but something about the medium makes it also feel very restrained. What's that contrast about? Curator: Well, consider engraving in the late 17th century: it's a printing method which means the dissemination of images was easier, particularly portraits of prominent people like Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor. Engravings allowed the image to be reproduced and sold at a fraction of what a painting would have cost, thus broadcasting the Emperor's image across different segments of society and regions of his vast territories. Editor: So almost a kind of royal propaganda disseminated on a mass scale...but in miniature? What I find so interesting is how the engraving manages to project authority with just lines etched into metal. It seems paradoxical, especially knowing the intense labour involved in the original production. What was the function of his image and the technique chosen to reproduce his likeness? Curator: It highlights a shift toward broader access to aristocratic representation, although of course literacy and visual culture at the time were deeply stratified. Engraving had become highly valued both as artistic form and commercial technique with specialized workshops employing different specialists in production such as those focused on text, design, or fine linework, all shaping how imperial power was visualized. Editor: This almost miniaturist method – I am also drawn to the calligraphic inscriptions at the bottom, and the crown that seems precariously balancing nearby – adds an ironic, vulnerable element that almost undermines its intended message. Curator: Interesting...that hadn't occurred to me. In any case, it allows for the circulation of imperial representation at an accessible price and reach across Europe, playing a key role in creating his reputation at the end of the 17th and early 18th centuries. Editor: It’s amazing how an object can function as both art and propaganda—almost handmade viral content if we saw the production and reach in today’s eyes! Thanks for shining a new light, or perhaps a softer focus on an engraving which allows us to pause. Curator: My pleasure! Reflecting on it now, maybe seeing how such production allowed the visualization of authority gives us a different perspective than say on oil portraits designed for purely aesthetic appreciation by those close to royal power.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.